Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2014/01/24/thirty_years_of_the_apple_macintosh_p1/

Apple’s Mac turns 30: How Steve Jobs’ baby took its first steps

Part 1: Love it or loathe it, the Mac shapes every nook and cranny of your computing life

Posted in Personal Tech, 24th January 2014 10:05 GMT

Feature Thirty years ago this Friday, at approximately 9:45am on Tuesday, 24 January, 1984, the Macintosh introduced itself after Steve Jobs unveiled it at an Apple shareholders' meeting in Cupertino's Flint Center for the Performing Arts.

"Hello. I'm Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag," the odd-looking 16.5-pound box said in its robotic text-to-speech voice, based on the Apple II's Software Automatic Mouth, the precursor to MacInTalk.

History is made of such moments – identifiable points in time before which something wasn't, and after which something was.

On the afternoon of Sunday, 20 March, 1983, for example, Jobs famously said to then–PepsiCo headman John Scully, "Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?" In one moment, Apple changed direction – as did not only the future of the Mac but also the career of Steve Jobs.

A few months later came another pivotal moment: at 10pm on an August Sunday, Mac programmer Steve Capps hoisted a pirate flag painted by Mac icon-designer Susan Kare onto the roof of the Bandley 3 building on Apple's Cupertino campus.

Before that night-time roof raid, the Macintosh division was essentially indistinguishable from other Apple workgroups in an increasingly bureaucratic company, one that was struggling to deliver on its commitment to the costly Apple Lisa and its game-changing GUI, the Mac's precursor. After the Jolly Roger flew, however, it was clear to all onlookers that the team was guided by one of Jobs' maxims: "It's better to be a pirate than join the navy."

The original Macintosh team, the original pirate flag, and the original Steve Jobs (lower right)

The thirty years since have seen many memorable moments in Mac history, some which brought good news to the Apple faithful – think System 7's introduction on the morning of 13 May, 1991 – and some which led in the opposite direction, such as the board meeting called hastily at 7am on 17 June, 1993, during which Apple CEO Scully was ousted and replaced by the arguably disastrous Michael Spindler, who nearly flushed the Mac maker down the toilet.

The Mac's ten-thousand, nine-hundred, and fifty-nine days have seen many decisive moments, but we've selected a mere 10 that we think are especially noteworthy. You'll likely disagree with some of our choices and have some alternate suggestions of your own – we'd love to read about them in the comments.

There can be no argument, however, about the Mac's significance in the history of personal computing. Supporter or detractor, you must admit that Apple's pioneering mass-market point-and-click PC has indisputably changed how we all interact with the digital world during the Mac's first 30 years.

As for the next three decades, well, your guess is as good as ours – but here's our countdown of the 10 most influential moments that have shaped the past 30 years. Happy Birthday, Apple Macintosh.

9am Friday, 16 May, 1997 – Steve Jobs seduces Mac developers

Steve Ballmer can rightly be faulted for his stumbles during his tenure as Microsoft CEO, but in perhaps his most famous performance in that role, he was spot on: when it comes to a platform's success, it all boils down to "Developers! Developers! Developers! Developers!"

But for Jobs, the focus was not on coddling developers by giving them exactly what they wanted. That wasn't Jobs' style. He could pull the rug right out from underneath them, destroy years of their work, and still manage to seduce them into The Macintosh Way.

Case in point: how he handled developers' outrage when Apple killed off OpenDoc, the document-centric software technology that asked developers to write small "parts" that could be pulled into documents to add bits of functionality. OpenDoc was part of a major, seven-year OS-redesign effort into which Apple – and scads of developers – had poured tremendous blood, sweat, tears, and resources.

Shortly after Jobs returned to Apple in early 1997, he strangled OpenDoc in its sleep – or, more specifically, he convinced then–Apple CEO Gil Amelio to do so.

On the morning of 16 May, 1997, during the closing keynote of Apple's Worldwide Developers Conference, Jobs entertained questions from the assembled developers. Apple's stock had closed that day at $4.31, down from $7.10 one year before and $10.94 the year before that. Apple was sinking; developers were bailing.

The first question was about the demise of OpenDoc. "I know a lot of you spent a lot of time working on stuff that we put a bullet in the head of," he answered. "I apologize. I feel your pain. But Apple suffered for several years from lousy engineering management. I have to say it."

The developers applauded.

"There were people going off in 18 different directions, doing arguably interesting things in each one of them," Jobs said. "Good engineers. Lousy management."

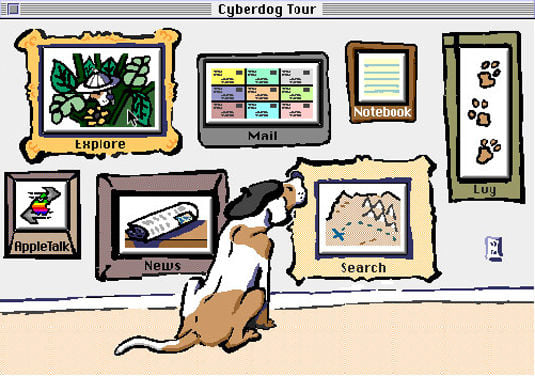

The Cyberdog browser, one of the few fruits of Apple's aborted OpenDoc effort

Jobs told the developers that he knew that he was going to "piss off people" by killing some longstanding projects such as OpenDoc, but that Apple had "had its head in the sand for the past many years."

One developer was having none of the kumbaya happy talk. When his turn at the microphone came, he quietly tore into Jobs. "It's sad and clear that ... you don't know what you're talking about," he told the Apple co-founder.

Jobs' five-minute response was a textbook case of using self-deprecation as an argumentative strategy, admitting ignorance without giving an inch, and winning the hearts and minds of an audience while doing so.

"Some mistakes will be made, by the way, some mistakes will be made along the way," Jobs said. "That's good, because at least some decisions will be made along the way. And we'll find the mistakes, and we'll fix them." Again, the developers applauded.

"Some people will be pissed off. Some people won't know what they're talking about. But I think it is so much better than where things were not very long ago."

He had 'em. They stayed – and some of them became very rich. Eventually.

Monday morning, 2 March, 1987 – The Mac II reverses Apple's fortunes

The original Mac 128K, 512K, and 512Ke were closed systems. Not only were they not the type of computers that would attract a business clientele – the IBM PC, released years before on 12 August, 1981, had that market sewn up – but they were also failing in the broader market.

Simply put, Jobs had been wrong: his idealized "toaster" of a closed, expensive-but-limited computer was not catching on among the general public, and the failure of the Macintosh Office, announced in January 1985, did nothing to move the Mac into the business world.

Too bad, Steve. Ater a power struggle with CEO John Sculley, Jobs was removed from the leadership of the Macintosh division. He soon resigned.

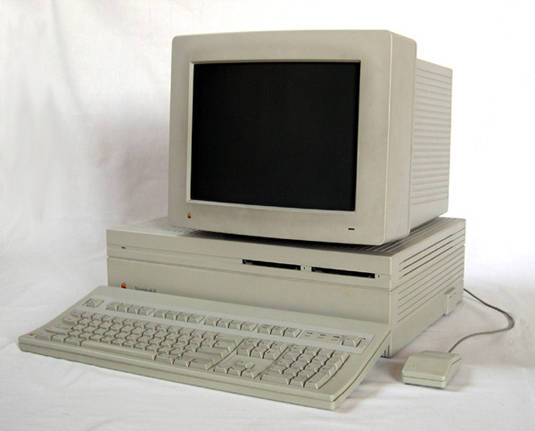

The keyboard, by the way, wasn't included in the $5,498 price for the 1MB RAM, 40MB hard-drive model

In January 1986, the Mac Plus was introduced. It added limited expandability through the addition of a SCSI port, but it was hobbled by the same 8MHz 68000 chip as were its predecessors. To be sure, it attracted more market acceptance than did its forebears, but not sufficiently in business – or, for that matter, in what would become the Mac's saviour, desktop publishing, despite the introduction of the LaserWriter on 1 March, 1985 and Aldus PageMaker for the Mac, also in 1985.

On 2 March, 1987, Apple released the Macintosh II (along with the Macintosh SE), and everything changed. Saying that the Mac II was a volte-face would be putting it mildly.

Most notable, perhaps, was the fact that the Macintosh II was expandable, thanks to its inclusion of six NuBus slots, a system developed at MIT and implemented in the Mac II in a 32-bit, 10MHz configuration. NuBus, by the way, remained the Mac's expansion slot of choice until Apple released the PowerPC 604–powered PowerMac 9500 in May 1995, which brought the industry-standard PCI bus into the Cupertinian fold.

But it was also the Mac II's processor that moved the Mac beyond its "sure it's innovative, cute, and easy to use, but what can I do with it?" status. Instead of that 8MHz 68000, the Mac II had a comparatively speedy 16MHz 68020 coupled with a Motorola 68881 floating point unit (FPU).

Although the Mac II is often referred to as the first colour Mac, it really wasn't, per se. It was merely "colour capable", with Color QuickDraw (PDF) in ROM. There was no graphics chippery on its motherboard – it needed a graphics card installed in one of its NuBus slots to drive its display, which Apple was happy to supply.

Development of the Mac II, it has been reported, was begun before Jobs left and without his knowledge. If true, that skunkworks project proved that there were still Apple engineers who lived by Jobs' earlier renegade credo.

Wednesday afternoon, 2 October, 1991 – The doomed but (somewhat) fruitful AIM Alliance is born

As the 1990s dawned, it was becoming increasingly clear that Apple's operating system was running out of gas, and that PCs running Microsoft Windows on Intel processors – "Wintel" machines – were eating Cupertino's lunch.

Even the crash-prone Windows 3.0, released in May 1990, gained adherents as its user interface – noticeably improved over that of Windows 2.1 – whittled away at Apple's advantages. The Redmond challenge ratcheted up a notch when the more-stable Windows 3.1 was released in April 1992, and it soon became abundantly clear that Apple had to make a move or it would be run over, gobbled up, or even worse: made irrelevant.

Apple, however, wasn't the only company threatened by the Wintel juggernaut. There were also the provider of the processors in its Macs, Motorola, and the maker of the original Wintel box, IBM, which had gone on to make its own major blunders in the personal-computing market – PS/2, anyone?

To counter Microsoft and Intel, it was only natural for Apple, IBM, and Motorola to do what comes naturally when faced with a powerful attack: they joined forces.

On October 2, 1991, the three companies announced the acronymically named AIM alliance, with the goal of creating a new hardware platform with software underpinnings that could take on Wintel.

Apple and IBM created two joint-venture companies, Taligent and Kaleida Labs. The former was staffed primarily with Apple engineers and tasked with completing a new operating system code-named "Pink", which had been under development at Apple since the late 1980s. The latter would work to develop the Kaleida Media Player, a cross-platform multimedia system that included plans for a settop box, and its object-oriented programming language and library, ScriptX.

Neither Taligent nor Kaleida Labs were successful, and both died later in the decade. Taligent was subsumed into IBM in the spring of 1996 and Kaleida Labs was shuttered at the beginning of that same year. A full exposition of their failures would require far more space than we have available here – moreover, this is a birthday party for the Mac, not a wake for those two flops.

It's the third AIM effort, however, that earns the inception of the alliance its place as number eight in our pantheon of important Mac moments.

We're talking about hardware – specifically the effort to build a RISC-based platform to counter the CISC-based Wintel world. In the early 1990s, the battle between reduced instruction set and complex instruction set computing had yet to morph into near meaninglessness, and IBM's POWER architecture was taking the RISC route among big-iron implementations.

Working together, the AIM alliance developed a single-chip, POWER-based processor dubbed the PowerPC. In addition, they also developed two reference platforms for the new processor: the first was dubbed PReP (PowerPC reference platform), and its follow-on was CHRP (pronounced "chirp", common hardware reference platform), which incorporated Open Firmware.

The AIM Alliance may have been a failure, but the PowerPC wasn't – for a while...

The "common" in CHRP's name referred to the fact that the platform was intended to run a variety of operating systems on its PowerPC processor, including the Mac operating system, Microsoft Windows NT, IBM OS/2, Sun Solaris, and IBM AIX. Unfortunately for the alliance, however, CHRP never caught on – although IBM used it for some of its RS/6000 boxes.

Apple, though, embraced the one AIM alliance effort that did bear fruit. In March 1994, Apple released three new desktops powered by the PowerPC: the "pizza box" Power Macintosh 6100, desktop 7100, and tower 8100.

For years to come – until Steve Jobs announced in June 2005 that his company was switching to Intel chips – the debate about whether PowerPCs or Intel chips were superior raged among the devotees of both processor families, fuelled in no small part by Apple's ads comparing Intel's Pentium II to a snail and the PowerPC G4 to a supercomputer.

And the AIM alliance itself? Hmmm ... Apple, IBM, Motorola – which still holds sway in the personal computer marketplace?

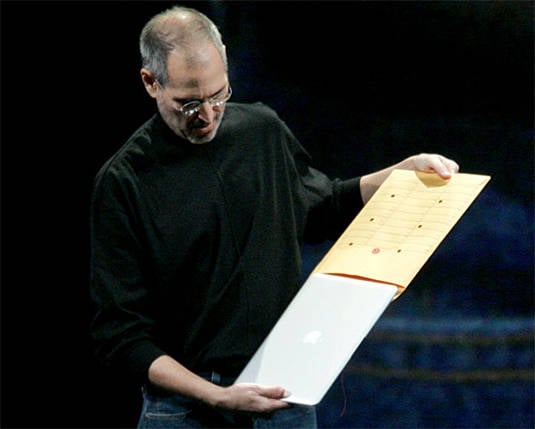

9:45am Tuesday, 15 January, 2008 – the MacBook Air invents ultrabooks before Ultrabooks™

As we mentioned earlier, on 24 January, 1984, Steve Jobs pulled Apple's Next Big Thing – the original Macintosh – out of a bag, wowing his audience. At about the same time in the morning a wee bit less than 24 years later, on the morning of Tuesday, 15 January, 2008, he unveiled another Cupertinian NBT. But this time he slipped it out of a manilla envelope.

'Hello. I'm MacBook Air. It sure is great to get out of that envelope'

The MacBook Air is now five years old, and the rest of the laptop market has only recently begun to catch up with it in terms of size, weight, and capabilities – and when it was introduced, it quite simply blew away the competition.

Sure, there had been "thin and light" laptops before – remember 2002's Toshiba Portege 2010? – but none had secured themselves a long-running niche in the market. The MacBook Air did, and it did so by Apple harking back to its slogan of a decade before: "Think Different".

When the Air was unveiled, it earned its share of brickbats – not so much for what it was, but for what it wasn't. Or, more to the point, for what it didn't include: an Ethernet port, an optical drive, a second USB port, FireWire (remember that?), and a removable battery.

Over the past five years, however, the complaints about the Air's missing bits have faded away, except among those users who had specific needs – and to whom, frankly, the Air was never targeted. Wired Ethernet has become a rarity for laptops, optical drives are disappearing as both software and content are increasingly delivered over the web (and the Air can share optical drives over Wi-Fi with both Macs and PCs), a second USB port was added in 2010, and FireWire is receding into history.

In addition, the lack of a removable battery proved to be no problem for most usage cases, especially nowadays as processors have become more efficient. In fact, the use of an internal, non-removable battery improved system battery life, seeing as how doing so obviated the need for all the attendant hardware required to make a battery removable. Less hardware, more space; more space, more battery.

But then there was the MacBook Air's price: the original 13-inch-only model started at $1,799 in the US and £1,199 in the UK, and popped rather significantly up to $3,098 and £2,028 if you replaced its pokey 4200RPM, 80GB hard disk drive with a 64GB SSD.

Those numbers changed, however – and significantly for the better. In October 2010, Apple introduced an 11-inch MacBook Air with a 64GB SSD for $999, and dropped the price of the 13-incher, with a 128GB SSD, to $1,299. Today, the 11-incher has double the SSD capacity for the same price, and the 13-incher with the 128GB SSD has had its price reduced to $1,099.

The original MacBook Air hid its audio-out jack and single USB and micro-DVI ports inside a flip-down flap

In May 2011, then–Intel CEO Paul Otellini introduced attendees of his company's annual investors' meeting to what was soon to be dubbed the Ultrabook™ – a design clearly cobbled together from MacBook Air specs. "This is the kind of device we expect people to be carrying around in the next 24 months or so," he said, not mentioning that Mac users had already had the opportunity to carry much the same device around for three years.

Finally, do you remember what the reigning lightweight mobile-computing devices were when the MacBook Air was introduced in early 2008? Yup: netbooks – underpowered li'l fellows with small keyboards, small screens, and small price tags. Netbooks peaked around 2010, and were soon displaced by tablets. They're essentially extinct now, but the MacBook Air retains its popularity.

That said, we wouldn't be at all surprised if the Air will be joined — replaced? — this year on the bottom rung of Apple's laptop ladder by the much-rumoured 12.9-inch, iOS-based "MaxiPad", perhaps with a Microsoft Surface–like touch cover, as has been rumored. That would give the Air about a six-year run – longer than the groundbreaking laptop form factor that we've picked for our next most-memorable Macintosh moment.

Monday morning, 21 October, 1991 – The PowerBook 170 redeems the Mac Portable fiasco

The kindest thing than could be said about Apple's first foray into the mobile-machine market, the Macintosh Portable, was that it was amusing.

At just under 16 pounds in weight, originally with a non-backlit screen, and powered by a turgid 16MHz Motorola 68000 processor, the big fella was a joke – and an expensive one, as well. When released in September 1989, it cost a cool $6,500, which translates to about $12,250 (£7,460) in today's dollars.

Needless to say, it failed.

Fortunately, it didn't take long for Apple to redeem itself by offering a trio of decent laptops into the marketplace, and by not only having one of those new machines be truly top-notch, but also by having all three introduce a simple but game-changing design element that every laptop manufacturer – that we know of, at least – has since imitated.

As Apple's SVP for marketing Phil Schiller said when introducing the new MacPro, "Can't innovate any more, my ass." Apple's laptop innovation was simplicity itself – as are the best forehead-slapping new ideas.

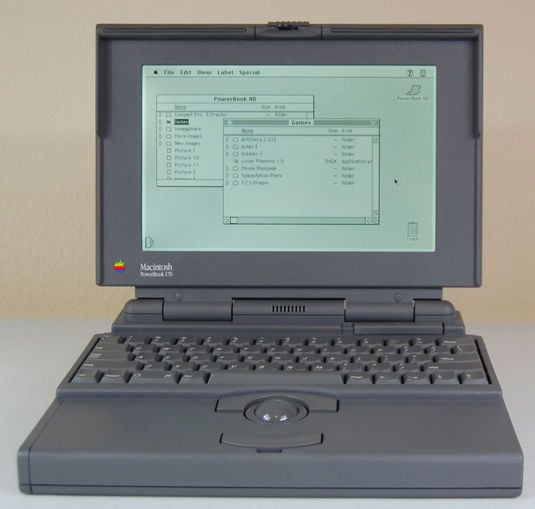

The concept of 'sexy product design' does change from decade to decade, mmmm?

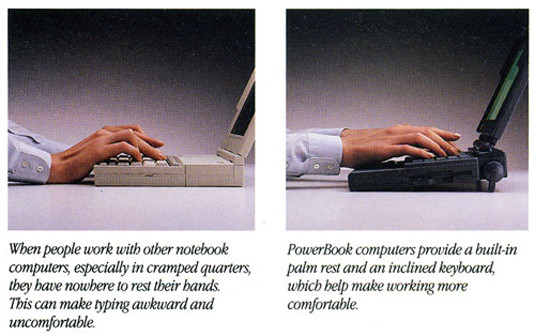

From the GRiD Compass 1011 to the Toshiba T1000 to the NEC UltraLite, early laptops, notebooks, or whatever you prefer to call them, had their keyboards on the forward part of the lower half of their clamshell cases.

However, one as-yet-unidentified Apple product designer – these were the pre–Jony Ive days, remember – had the bright idea to move the keyboard to the back of the lower case, thus adding not only palm rests, but in the case of the PowerBooks 170, 140, and 100, announced on Monday morning, 21 October, 1991, also room for a cursor-controlling trackball as well.

As of that morning's PowerBook introduction – at the now-defunct, soup-to-nuts Comdex computer confab in Las Vegas, oddly enough – Apple was not only no longer embarrassed by its ludicrous Macintosh Portable misstep, it also regained respect as an industry innovator, a company to watch.

Such a simple, obvious idea – why didn't any major laptop maker think of it before?

Of the three PowerBooks introduced that day, the most forgettable was the PowerBook 140, with its passive-matrix LCD display. You young 'uns may never have been exposed to such a smeary, messy morass of pixels, but they died a quick death as soon as active-matrix displays became affordable during that same decade.

The smaller PowerBook 100 – manufactured for Apple by Sony, by the way – was an odd duck, beloved by many but disdained by an equal number. Also lumbered by a passive-matrix display, at just over five pounds it had the advantage of being noticeably lighter than the nearly seven-pound 140 – although its lack of a floppy drive may have helped that weight reduction, it hampered its useability. In 1991, at least.

The star of that October morning was the PowerBook 170. Powered by a quite-snappy-for-its-day 25MHz Motorola 68030 processor assisted by a 68882 math coprocessor, the 170 was equipped with an active-matrix black-and-white (well, black-and-greenish) LCD display, a luxury accoutrement at the time.

The PowerBook 170 was 2.25-inches thick; 17 years later, the MacBook Air's thickest measurement was 0.76 inches.

Users, however, paid dearly for that display and that processor power (the PowerBook 140 had a 16MHz 68030 and no math coprocessor): the 170 retailed for $4,600 – $7,900 today – while the 140 could be had for just $2,000.

Despite that price, companies bought them for their road warriors [Full disclosure: I was one of those grateful beneficiaries — Rik], and Apple gained a foothold into the business market.

Again. For a while. ®

Part II of The Register's Mac 30th celebrations will be out this afternoon. Stay tuned, folks!