This article is more than 1 year old

UK's first transatlantic F-35 delivery flight delayed by weather

Airliners do it all the time - but these aren't airliners

Comment Britain’s first permanently UK-based F-35 fighter jets are not arriving in Norfolk today as expected due to RAF concerns about bad weather.

The open secret of the aircraft’s arrival date is being widely discussed on social media, following defence secretary Gavin Williamson’s announcement that the supersonic stealth jets will be arriving at their new RAF Marham home some time this month.

Four of the new fighters, of which the UK currently owns 15, are due to fly across the Atlantic in a marathon 6,440km (4,000 mile) journey. Such a long journey is filled with non-obvious risks, not least because the jets need air-to-air refuelling at a number of points during the journey.

While to the casual reader the idea that the new £85m-apiece fighter aircraft cannot fly in less-than-perfect weather (at the time of writing large parts of the UK are cloudy with sunny intervals) seems bonkers, the full picture is more complex than that.

Crossing the Pond

Transatlantic flights are routine. Airliners do them all day, every day, so the RAF being unable to do it with brand new aeroplanes means they’re a laughing stock, right?

Not so much. Transatlantic flights with airliners (and converted airliners, such as the Air Force’s Airbus A330 Voyager tankers) are routine because those aircraft have two or more engines, at least two pilots, an onboard toilet and a kitchen. In the event a pilot becomes unwell or needs a cup of coffee to help stay alert, someone else is there to take over and refreshments are on hand. If one of the engines stops running, you’ve got a second one that is designed to take the strain and get you to a diversion airfield.

An RAF Airbus Voyager tanker-cum-troop transport aircraft. These will be used to refuel British F-35Bs in flight. Pic: MoD/Crown copyright

In the world of twin-engined airliners, this is called ETOPS, which stands for Extended-range Twin engine Operational Performance Standards. An airliner certified for ETOPS flights can legally make flights that take it several hours’ flying time away from the nearest airfield suitable for an emergency landing. More advanced ETOPS aircraft such as the A330 and the Boeing 787 can even go up to 330 minutes (five and a half hours) away from diversion airports. Certification is, roughly speaking, based on engine reliability.

Going solo

This is not the case with a single-seat, single-engined fighter jet, which, aside from having no creature comforts except for a seat and an air supply, is a lot riskier (from the planning point of view) to fly over the sea for long periods of time. If the engine stops delivering full power, that aircraft will go down.

Thus you have to start taking potential practical problems into account: in the case of our F-35 transatlantic flight, how you’re going to rescue the pilot if he has to bail out. If the weather is crap or the sea is rough, how is your air-sea rescue team going to find him? How long will they take to get there and actually locate the pilot? Bearing in mind sea temperatures and human life expectancy, how long can you risk leaving him in the sea while you find him?

ZM137, one of the UK's F-35Bs, pictured visiting Britain in 2016. The tail numbers of the jets arriving in the UK are not yet publicly known. Pic: MoD/Crown copyright

The Health and Safety Executive in the UK published a study some years ago into human survival rates in the North Sea in typical winter conditions, focusing on sailors being forced to abandon their ships. It concluded (PDF) that “a group of uninjured survivors immersed in the North Sea in typical winter conditions and wearing twin-lobe lifejackets and membrane immersion suits,” would probably begin to die within half an hour of entering the sea. While the North Atlantic is warmer, with the former averaging 15 degrees Celsius at this time of year as opposed to 6 degrees C for the North Sea in winter, you still need to find a hypothetical downed pilot and get him out ASAP. Inclement weather, be it clouds that limit how high a search aircraft can fly or a heavy sea state, pose a real risk.

It doesn’t matter how thoroughly tested the aircraft is: on your peacetime delivery flight, you don’t take unnecessary risks with either the jet (which is easily replaced) or the pilot (who isn’t).

Whither the weather?

Moreover, the planned F-35 delivery flight relies on air-to-air refuelling to complete the 6,440km (4,000 mile) flight, the aircraft having a quoted range of around 900 nautical miles and therefore an extreme endurance of around 1,800 miles. Doing the sums, one would expect there to be a minimum of two refuelling points on the journey from their current location on the US Marine Corps airfield at Beaufort, South Carolina, to RAF Marham in Norfolk.

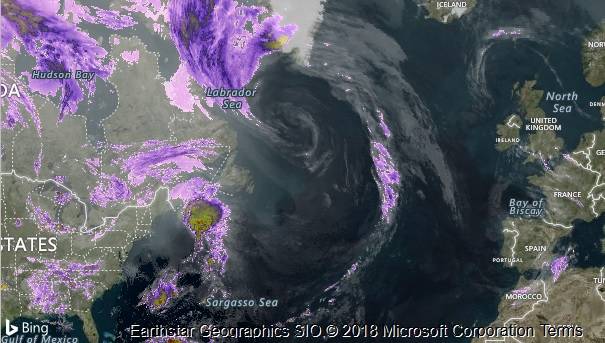

For obvious reasons air-to-air refuelling needs calm weather to successfully take place; turbulence and thick cloud are kryptonite to refuelling. Below is a radar snapshot of the weather to the west of the UK, which the delivery flight would have to pass through.

North Atlantic weather satellite. Note carefully the big thunderstorm immediately north-east of the USA, and the thick clouds (shown in purple) in mid-Atlantic. Pic: Accuweather/Microsoft Bing

As you can see, weather conditions are less than perfect. Again, why take the risk when you can wait a few days and see how things pan out? The worst-case scenario is that a planned air-to-air refuelling serial doesn’t take place and your four brand new fighter jets and their pilots either have to rush back to the start, wasting time, money and effort, or they force-land on any available spit of land – or even ditch the jets and bail out, triggering a rescue and recovery operation.

While your correspondent’s experience of flight planning and indeed aviating is minimal, these are the sorts of things that suggest themselves.

The British decision to conduct an all-in-one transatlantic flight to get our new F-35Bs over here is a bit of a flag-waving option to show to the world that the UK hasn’t lost the skills to operate fighter aircraft at great distances from their home bases. The safest flight-based choice would be to route overland via northern Canada, Iceland and Greenland, stopping en route, though that brings a whole level of diplomatic faff to secure clearance for military aircraft to land and refuel in those countries and also extends the journey over two or three days.

Yes, the RAF could just accept the risks and push on regardless - but if something went wrong that would be a catastrophe which would reduce the UK to an international laughing stock. In the present day and age, perception counts for an awful lot.

Of course, the safest choice of all would be to box up the F-35s and have them put in containers to be shipped from America to the UK, though, according to the old aphorism that Grace Hopper was so fond of: "A ship in port is safe. But that's not what ships are built for." ®