Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2007/06/22/protecting_data_usenix/

Digital data can bite you in the ass, researcher warns

Beware of those contributions on Flickr and Myspace

Posted in Security, 22nd June 2007 22:21 GMT

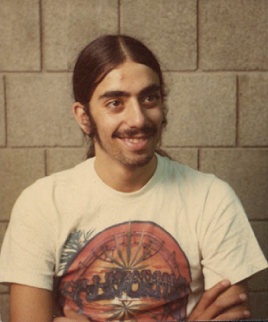

Usenix When security consultant Dan Klein was culling decades-old snapshots for his digital scrap book, he specifically omitted photos taken during his college years, when some of his behaviors weren't exactly role-model material for his offspring. Left unscanned, for instance, was the picture of him wearing a tee-shirt bearing a marijuana leaf or another one showing him brandishing a six-inch switchblade while sitting in front of the pelt of an endangered animal.

Because the pictures were shot in the 1970s, preventing them from seeping into the digital ether was a trivial matter that required only that he keep them in the same musty closet that had been their home for years. Klein's secret was safe...until now.

Contrast his experience with the students Penn State University students who rushed the football field in 2005 after a their team led a stunning defeat of Ohio State University. Police investigating the disturbance were able to identify some suspects using images posted on Facebook, including some bearing the title "I Rushed the Field After the OSU Game (And Lived!)."

"We're living at the dawn of a new age, or participating at the dawn of a new information age," Klein said during a session at the Usenix Annual Technical Conference in Santa Clara, California. "Whether it's good or bad, whether it's correct or incorrect, the data is preserved forever."

Klein's 90-minute talk was packed with plenty of other cautionary tales. There was the Google search from Robert Petrick's computer for "Body decomposition" and "neck," "snap" and "break," that helped lead to his conviction for the murder of his wife and the dumping of her body in a North Carolina lake. Scott Peterson, who was convicted of murdering his wife and dumping her in the San Francisco Bay, was similarly implicated by a Google search, in his case for queries relating to tide schedules.

There was also the former nanny of a friend who maintained a blog on LiveJournal that volunteered that she was a survivor of child abuse. The friend, acting in response to statistics that suggest past abuse is a strong predictor of future abuse, fired the woman.

Indeed, Klein himself has been snared by stale digital information that later got dug up. In his case, the offending document was a PowerPoint presentation he gave for a Usenix talk years ago in which he discussed his experience providing technical support to a variety of adult-themed websites.

"In a lot of people's minds, I'm that porno guy," he said.

The latter anecdote demonstrates how easy it is for digital information to be misconstrued. Despite all the lessons about the inaccuracy of Wikipedia and other digital repositories, we still give a great deal of credence to what we see online. The means even seemingly benign details can become liabilities if they are misrepresented.

Of course, search engine queries, blog postings and photo sharing are only a few of the ways personal data can leak out in ways we never intended. RFID tags are already being embedded in passports, and laws have already been proposed to put them in driver's licenses. Given technologies that extend the range at which tags can be read, Klein said, it's not a stretch to imagine readers being installed in doorways, roadsides, walls and other places and having our comings and goings monitored.

"Once you know where somebody is, you can do correlations," Klein said. "That is the greatest boon and the greatest threat of the information age." An example of a useful correlation: a reminder to renew an eyeglass prescription a few years following a visit to an optometrist that was logged by a mall's RFID system. More invasive is the report sent to the health insurance provider that the person just ate two jelly doughnuts at the cafeteria.

There are also more immediate ways to monitor someone. A service provided by World-Tracker makes it possible to monitor the real-time location of cell phones anywhere in the UK. "I registered my girlfriend while she was in the shower," Klein joked.

There are also more immediate ways to monitor someone. A service provided by World-Tracker makes it possible to monitor the real-time location of cell phones anywhere in the UK. "I registered my girlfriend while she was in the shower," Klein joked.

If there was a shortcoming to Klein's presentation, which was titled "Perfect Data in an Imperfect World," it's that he never articulated a solution to the problem. "I want to be able to control my digital information, I need some sort of digital rights management," he said, without elaborating on how we might bring such a thing about. "It would be nice if digital materials had a limited life and limits to accessibility." Yeah, and we'd like to eat ice cream three times a day, too.

Lest Klein appear as an alarmist, it's worth noting that he's not squeamish about collecting, and in many cases, sharing huge amounts of information related to him He records a wealth of information relating to the environment around his home, including its location, hot water usage, lighting, temperature and air-conditioning activity.

A few minutes after his talk ended, he checked one graph he makes publicly available and was able to deduce that his girlfriend probably took a shower the previous night around midnight. He also detected that there had been lightning earlier that evening. His site also includes plenty of other details, including his phone number, postal address and global positioning system coordinates for his home located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

"What do I have to hide?" he said with a shrug. "Because all that information is elsewhere, I'm not worried about publishing it."

But he closely guards other information. His MacBook Pro, for instance, logs every IP address he uses to connect to the net and periodically snaps an image through the laptop's built-in camera. He permanently logs every incoming and outgoing cell call. While he archives this data, he doesn't make it available publicly.

Ultimately, Klein's message seems is that we must recognize that there is no way to recall anything we say or do publicly, and therefore we have to balance the benefits of having digital data against their risks.

"When you're in a position to publish the data," he said, "just be aware of what can be done with it." ®