Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/10/24/elan_flan_enterprise_micro_is_30_years_old/

Phantom Flan flinger: The story of the Elan Enterprise 128

DCP, Samurai, Oscar, Elan, Flan, Enterprise - the micro with six monikers

Posted in Personal Tech, 24th October 2013 09:04 GMT

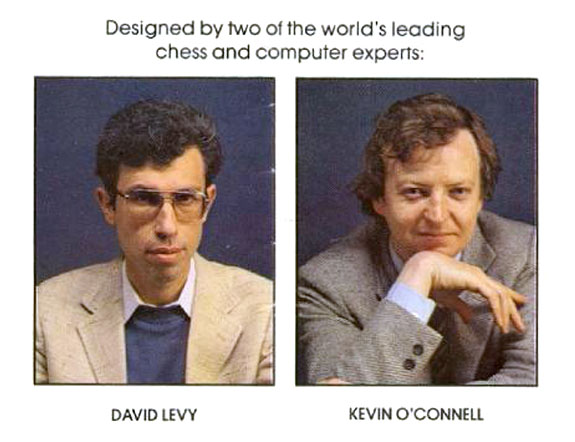

Archaeologic Despite its name, Intelligent Software also had a nice little sideline designing hardware. Founded in 1981 by international chess champion David Levy and chess writer Kevin O’Connell, the company was best known for its chess programs, in particular Cyrus and SciSys Chess Champion.

But it also developed chess computers for toy company Milton Bradley, for Hong Kong-based CXG, for SciSys and for Ries, a Parisian distributor of chessboards.

The latter device, called La Regence, was created during 1982 after an encounter between the two companies’ principals at the January Consumer Electronics Show (CES). The chess machine was based on a 4MHz Z80A processor with 1KB of RAM and 12KB of ROM to hold the operating system and the chess program, a version of Richard Lang’s Cyrus. Intelligent Software had acquired Cyrus in 1981, and hired its maker, Lang, at the same time – to maintain his software.

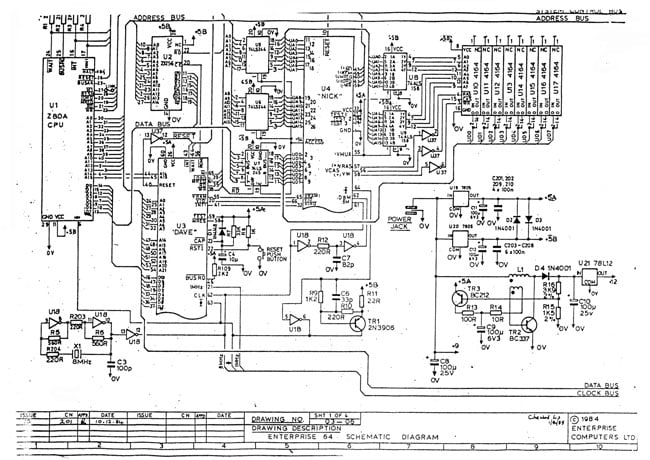

The Enterprise 64

Source: Compi Diaries

The development of the La Regence hardware was contracted out to Nick Toop, an engineer who after graduating in the late 1970s had gravitated toward Clive Sinclair’s Science of Cambridge (SoC). SoC’s day-to-day manager, Chris Curry, soon established Acorn, and for a time the two businesses happily co-existed.

Acorn eventually broke free, and Toop went with Curry, most notably creating the Atom out of the existing Acorn Microcomputer board machine. By this stage Toop was also doing hardware design consultancy.

While work was progressing on La Regence, IS was approached by what press reports would go on call “a consortium of British and foreign investors” and, later, “a bank on behalf of a mystery backer” with a contract to design a home computer. In fact, it was Domicrest, an Anglo-Indian trading company then based in East London, whose principals, Deepak Mohan Mirpuri and Mohan Lal Mirpuri, had been inspired by the April 1982 launch of the Sinclair ZX Spectrum to enter the computer market themselves.

Domicrest was already well known to the IS team. Deepak Mirpuri played squash with IS's accountant, and his interest in entering the consumer electronics business was relayed to Levy, O’Connell and their newly appointed technical chief and fellow director, Robert Madge, who had just been brought on board to manage IS's hardware efforts.

From personal assistant to personal computer

Today, David Levy describes Madge as “very creative, very technically creative... very smart, an all-round genius”, and it was Madge who devised and led the development of the Pad, a PDA-style pocket calculator device that Domicrest had first approached IS to build. The Pad would then be released under a new brand, Biztech.

But, having started work on the Pad, Madge quickly became more interested in the exploding home computer market. He may have persuaded Deepak Mirpuri to fund the development of a home computer, or Mirpuri may have decided separately that that was the way to proceed. Possibly both men arrived at the notion separately. Other IS people undoubtedly thought the same. As David Levy says now, back then “everyone knew that home computers were selling like hot cakes”. Whomever prompted the decision, the result was a change in direction and the formation of a new company, jointly owned by IS and by Domicrest, to market the new home machine.

The two firms’ bosses all took directorships of the new firm, and the Mirpuris introduced Levy, O’Connell and Madge to Lachu Mahtani, owner of a London-based insurance underwriting business called Locumals who had been persuaded to provide the extra funding they would need to develop a micro and bring it to market.

The Enterprise project began in earnest in October 1982 under the bizarre codename "Damp Proof Course", apparently intended to dissuade anyone who found a misplaced copy of the plans from eyeing them up too closely. Most of the early Enterprise documentation is stamped simply "DPC".

Enter the Samurai

Shortly afterward, Samurai Worldwide was founded as the company under which the computer would be manufactured, marketed and sold. Intelligent Software’s three directors, David Levy, Robert Madge and Kevin O’Connell, became directors of the new firm, as did Lachu Mahtani, and Deepak Mirpuri and Mohan Lal Mirpuri of Domicrest. Madge was also named Samurai’s technical director.

The R&D work was contracted back to IS, which expanded its team to 20-odd people, David Levy recalls, in order to support the development of the new computer’s operating software and applications. Because IS had a good working relationship with Nick Toop, he was asked to design the computer’s hardware to a specification set by Madge.

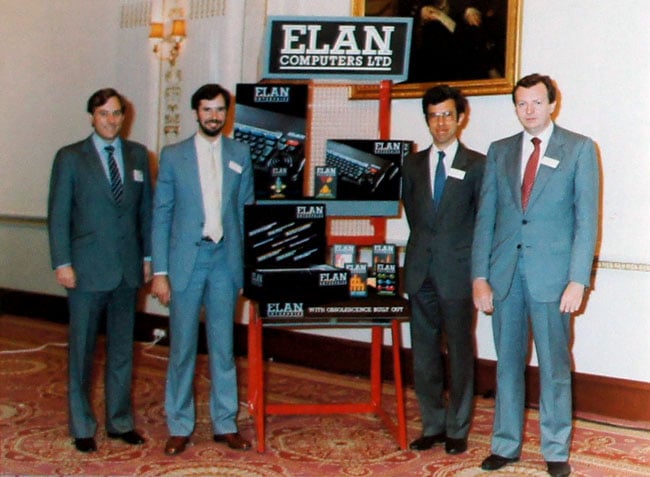

Executives with Elan: (L-R) Mike Shirley, Robert Madge, David Levy and Kevin O’Connell

“What we were asked to do in our brief was to design a computer which would be among the top few sellers, which would appeal on a whole number of levels - for games, for home business, for enthusiasts and novices, and also appeal to commercial software houses who will have to produce material for it if it is to be a success,” said Madge in October 1983 during an interview with Popular Computing Weekly. In fact, the Enterprise and its specification was as much Madge’s as anyone’s - if anything, more so.

Madge would later reveal that his initial thinking called for more of a direct Spectrum rival than the Enterprise would eventually turn out to be: Madge found himself “going down the same sort of path Oric went down”, he told Your Computer in 1983.

That idea was soon rejected, however. The feeling was that by the time the machine came out, it would have already been superseded. The logical alternative to starting at the low end of the market and working up was to start at the high end and to wonder, as Madge put it, “If we could have everything, what would we have?” It was the same approach that governed the work on the Memotech MTX, then under development too.

‘The best computer on the market’

“Robert wanted to produce the best home computer on the market,” remembers David Levy. “Throughout the time I knew him he was a maximalist. He always wanted to produce the best of whatever it was he was involved in. He quickly came to the conclusion that we should have the best graphics and the best sound around, and that the only way to do it was to develop two ASICs, one for graphics, one for sound.”

Cost and pricing factors led to some of the more advanced options being whittled away as Madge and his team tried to zero on on “a technological window for a product which answered most people’s complaints about existing home computers [yet could be set] at a reasonable price”. He had a long view - justifiably as it would turn out. The machine, like its parent company also called Samurai, had to “still be wanted four or five years after the original design decisions were taken”.

Nick Toop’s work with the Z80 processor, along with the prospect of being able to run the CP/M operating system then the de facto standard for business micros, ensured there was little choice but to base the machine on the Zilog processor. The need to run CP/M suggested 64KB would have to be the base memory capacity. It would also provide a selling point against the 32KB and 48KB machines then on the market.

While IS was responsible for the internals, the computer’s industrial design was put out to tender. Three teams of designers were asked to present their vision of the new machine. Business partners Geoff Hollington and Nick Oakley, both entirely new to computer design at that time, were among those canvased for their interest in the project.

Designing for the living room

Hollington had trained in product design, but his career had taken him into interior design, with work on Island Records’ studios and Vidal Sassoon salons to his credit by then. By 1983, he was running his own agency in Belsize Park, London in an office shared with former journalist and Design Magazine editor Mark Brutton. Robert Madge, Geoff remembers, had an interest in architecture and design, and knew Brutton. Keen to put to practice the product design skills he’d learned at college, Hollington jumped at the chance to pitch for the Samurai when it the opportunity was given to him.

Hollington and Oakley promised a fast response to Samurai’s overtures, but it was their notion that computers needed to move beyond the "rectangular beige box with a keyboard on top" look then commonplace and become items designed to sit comfortably alongside TVs and hi-fis that won them the Samurai gig.

The two wanted the design, as Hollington put it in a 1983 interview, to “seduce people into buying the machine yet say little about the technology” within. Apple’s Jony Ive might today say the same thing.

Lacking sufficient expertise, IS had had to seek industrial design experience outside of its in-house team. It also needed to look elsewhere for help designing the new machine’s core logic, the two sound and graphics ASICs at the heart of the design. Madge had originally hoped to build the Samurai entirely out of off-the-shelf parts - “there is no point reinventing the wheel”, he would later say - but when it came to video and audio, nothing then on the market was judged to be up to snuff.

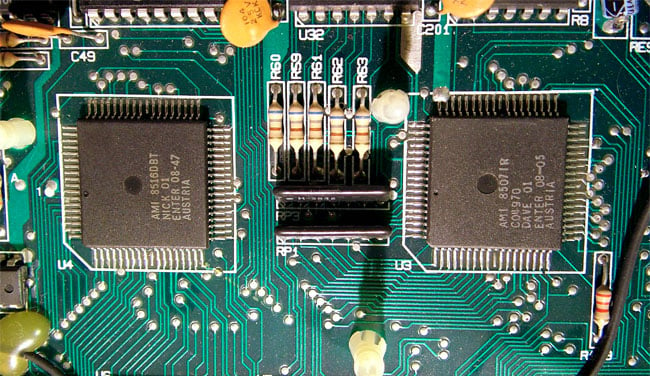

So Madge took the brave step of commissioning the development of the two new chips. Nick Toop was asked to design on the video chip. He soon became IS’ chief engineer and later a company director thanks to his work on the first of the two ASICs and on the rest of the computer’s electronics. His chip was unimaginatively nicknamed "Nick".

Chip customisation

For the other part, Madge brought in Dave Woodfield, whose talent had helped secure victory at a national micromouse competition. A micromouse was a compact robot able to find and remember the fastest successful path through a maze. Madge figured Woodfield would have no trouble navigating the complex pathways of a new audio processor.

In addition to sound, the "Dave" chip also handled memory management. The Enterprise divided its 64KB memory into four 16KB "segments", with four more in the 128KB version, and 256 in total for the full 4MB of RAM or ROM - 3.9MB in practice. Dave performed the trick of recording memory addresses as 22-bit values and ensuring required 16KB memory segments blocks map into any one of the four 16KB pages supported by the Z80. Dave was also responsible for managing the 1MHz system clock, the interrupt system and the system reset circuitry.

The custom chips: ‘Nick’ and ‘Dave’

Source: Enterprise One Two Eight

The machine’s I/O system was based around a channel structure, accessible through Basic and EXOS, and with each device - keyboard, screen, cassette, printer, etc - assigned its own channel.

By this point, Hollington and Oakley had largely completed their case design, on schedule. Notions that the expansion cartridge might go on top of the machine had been rejected in favour of a side-facing location, the better to prevent spilled drinks getting in, apparently. Equipping the computer with a standard keyboard had been dismissed too, for cost reasons. Instead, injection moulded keycaps would be placed on top of a Spectrum-style rubber-mat-and-membrane keyboard to combine the latter’s low production cost with the hard-key feel that the team believed would appeal to touch-typists and lend the product an air of quality.

Italian design

Geoff Hollington say the look of the keyboard was inspired by the work of Italian typewriters-to-technology company Olivetti, which had steered a path away from the thick, blocky keys pioneered by an ergonomics obsessed IBM. The large space bar required the addition of cantilevering to prevent either end getting stuck down, he recalls, and the same mechanism was applied in miniature to the Enter key.

The built-in joystick - which had always been in Robert Madge’s specification, Geoff recalls - was designed by Nick Oakley. It was mounted on a cruciform plastic panel so it would trigger membrane keys set beneath it. The handle screwed on. Those were practical necessities - Oakley’s contribution was the corrugated rubber surround, which helped give the unit a futuristic look but more pragmatically kept the internals sealed away.

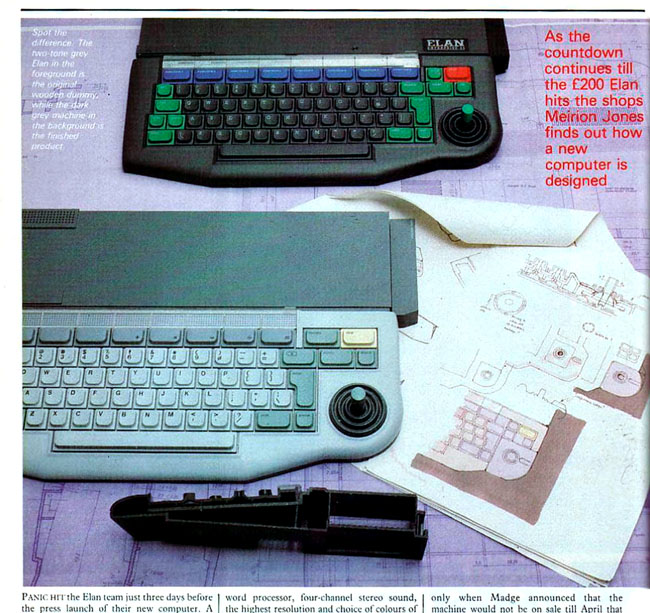

Geoff Hollington’s original colour scheme makes a surprise appearance in Your Computer

In February 1983, model maker Ken Houghton was tasked with producing a mock-up from the designers’ blueprints. It was painted in two shades of grey: the rear, rectangular section was dark grey, the curvy section at the front light grey. Hollington applied the same two-tone colour scheme to the keyboard: alphanumerics in light grey, function keys dark. The important Stop key was colour lemon yellow, another nod to the Italian design flair that so impressed Hollington.

The design was approved, and Hollington and Oakley drew up blueprints on tracing paper which, over Easter that year, their sculptor turned onto graphite armatures from which moulds could be formed. So complex was the final assembly, it required no fewer than seven toolmaking firms - all hired and managed by an engineering agency, Geoff recalls - to produce the rigs which would be used to cast the final plastic casing.

Name change number one

It was too complex, of course, and the moulding went wrong. Parts came out the wrong size - too big rather than too small, fortunately. Making fresh moulds was deemed too costly so the existing ones were just cut to size. A botch to be sure, but one the Samurai team and the designers hoped wouldn’t be noticed. By and large, they got away with it.

They got away with the external heat sink too, though it had originally been intended to sit within the case, says Hollington. But the electronics used to regulate the power just got too hot and it was feared the heat might damage the case. So the extruded aluminium block, which was still directly connected to the power circuitry, was shifted to the back of the box where it could extend out of the case.

Staking a claim to the Samurai brand - but the company’s effort proved unsuccessful

By this stage, however, case construction was proving to be the least of the operation’s worries. In the Spring of 1983, a computer reseller called Micro Networks began to offer a £3000 16-bit business computer also called Samurai, this one based on kit from Japan’s Hitachi - hence the name.

In a bid to establish its ownership of the name, Samurai placed ads in the computer press announcing that “the Samurai home computer is coming...” and stating that “Samurai is a trademark of Samurai Worldwide Ltd”. The ads said nothing more. They gave no indication of specs or pricing, or indicated when the machine might ship.

Robert Madge would later insist that Samurai had correctly registered the trademark, and done so before Micro Networks had launched its business micro. But a check of the UK current trademark database, which goes back well beyond the years we’re considering here, reveals the only ‘Samurai’ trademark registered in 1983 was for a brand of Italian toothpicks. Whether IS failed to register the trademark correctly, the application was for some reason rejected, or it had simply not been granted in time to stop Micro Networks isn’t known.

Re-branding the box

Whatever the reason for Samurai’s failure to protect its preferred moniker, the brand was now judged to be unusable. A new one had to be found. ‘Oscar’ was briefly considered but soon dropped in favour of ‘Elan’, a name that it was hoped would suggest a dashing, stylish product, but would eventually prompt another, highly embarrassing change.

For the moment, though, other alterations were being made. The graphic designer brought in to devise the Elan’s branding and to create the look of the computer’s instruction manuals and brochures came up with a colour scheme of hard primary hues over a black background - undoubtedly reflecting, in Geoff Hollington’s view, what Sinclair had done with the Spectrum.

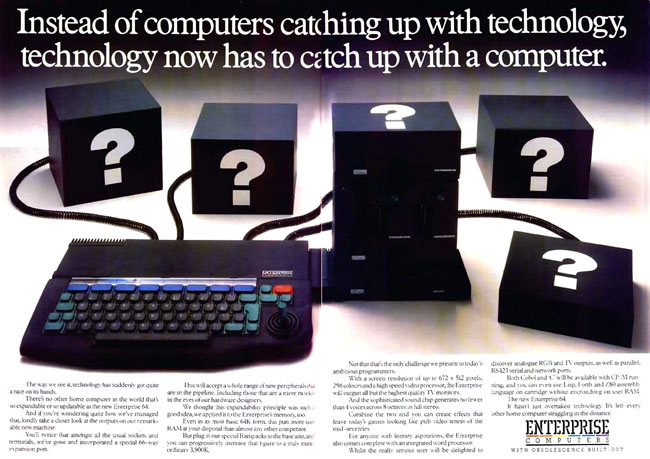

The Elan Enterprise was initially promoted on the brainpower of Intelligent Software’s founders, not on the skills of its real designers

Most likely the graphic designer suggested to Robert Madge that perhaps the computer should adopt the same scheme, but wherever the notion came from, it was soon made official, much to Hollington’s ire. Today he dismisses the machine’s red, blue and green keys, set on a pure black casing, as “Lego block colours”.

With a new name chosen, and development of both the hardware and the software proceeding apace, it was decided to launch the new computer, now also dubbed the Enterprise. Elan began briefing the press in August 1983, in particular emphasising David Levy’s background as a chess champion and thus IS's software brainpower. Perhaps IS hoped to spoil the long-delayed launch of the Acorn Electron, which took place that same month. During the briefings little was said about the computer itself - not on the record, at least.

Launched with a long lead time

Journalists and readers would have to wait for speeds and feeds until 14 September when the Enterprise was launched. It made its public debut three days later, at the Olympia-hosted Great Home Entertainment Spectacular show. Up until then, they would just hear “I have absolutely nothing to say,” from IS's Kevin O’Connell. “No information will be released until we are 100 per cent ready. I’m afraid I’m going to continue to stonewall you.”

That September the Elan Enterprise would be presented in two versions, one with 64KB of RAM, the other with 128KB. Both would have a 4MHz Z80A processor and 32KB of ROM for the operating system and, novelly, an integrated word processor. Memory could be extended to just shy of 4MB - a staggering amount at the time - but only with a series of stackable add-on modules coming some time after the machines themselves.

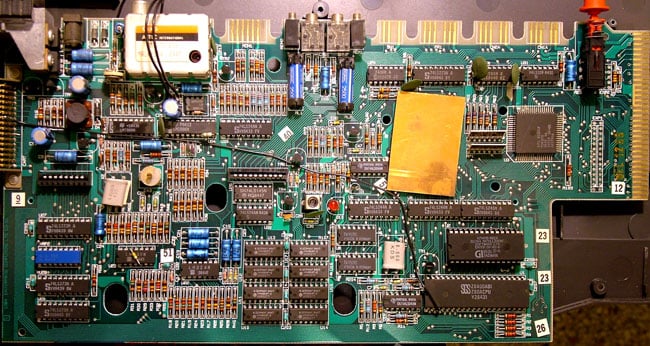

The Enterprise 64 motherboard

Source: Enterprise One Two Eight

Nick Toops’ video chip would provide support for 256 colours, with text screens running from 42 x 28 characters to 84 x 28, both using four pairs of foreground and background colours from the full palette. Graphics screens could reach a resolution of 672 x 256, though at a cost of colour range: at that resolution each horizontal line could use only two colours. Reduce the horizontal resolution on any given line and more colours became available.

Dave Woodfield’s sound chip would let the Enterprise output four stereo channels simultaneously - three music channels and one for noise - through the micro’s own speaker or out of a 3.5mm socket on the back of the computer.

Back to Basic

In addition to the Rom cartridge slot - capable of adding 64KB to the Enterprise’s memory map - the computer had two cassette ports, two non-standard joystick ports, and both Centronics and RS232 connectors for printers and modems. An expansion slot provided an interface for the extra memory modules and promised peripherals, such as 3.5-inch floppy drives. Expansion bus-connected devices could directly and automatically patch the Basic Rom with extra, appropriate commands.

The bus included not only lines to the processor but was also hooked up to the video and sound chips. That would allow, say, video to be playing into the machine.

“With the whole design of the Elan, we have not tried to produce something fundamentally new,” Robert Madge told Personal Computer Weekly in October 1983. “Just better [and] with all the good features from other machines taken and developed as fast as possible.”

There was still work to be done. IS had the Enterprise’s operating system, EXOS (Enterprise eXpanadable Operating System) and Basic interpreter - which would not, like the ones in so many UK home computers, be built in but supplied separately on Rom cartridge - running on other computers, but not on the Enterprise itself.

Much earlier, Elan had approached other companies for a Basic interpreter, an approach consistent with Madge’s off-the-shelf parts strategy. It certainly got in touch with Microsoft which then produced the closest thing there was to a standard version of the language.

But Microsoft, Madge would later claim, wasn’t keen on tweaking its Basic to make the most of the Nick and Dave chips. “They just wanted to hand over a complete package,” he said.

American sighs

So IS got the gig instead and went on to code a version of the popular language based around the ANSI (American National Standards Institute) specification. “We wanted a Basic which was likely to be accepted as the standard programming language of the future - a version which would answer most of the objections people make to Basic,” said Madge. “In the Elan, I think we have achieved that.”

Right through to the end of 1983 and beyond, IS would be working to get the Basic and OS code running on prototype Enterprises. No wonder Robert Madge had to disappoint some folk when, at the Enterprise launch, he admitted that that computer wouldn’t go on sale for another seven months: it would ship in April 1984. The seemed an age to observers of the fast-moving UK home computer business. Peripherals would not arrive until June 1984.

Intelligent Software’s key coders: (L-R, rear) ??, ??, ??, Richard Lang

(L-R, front) Martin Bryant, Mark Taylor, ??, ??, ??, ??

Know the missing names? Please pass them on.

Neither deadline would prove easy to meet. Like many a computer maker before it, Elan found that making a working custom chip was not straightforward - and it had two in the works. Problems with the video and audio chips became public knowledge toward the end of 1983, forcing the company to admit that independent software developers - the games and applications writers Robert Madge had only recently said were essential to the success of the Enterprise - would not get their hands on sample kit until February 1984, a month later than planned.

Still confident, the Elan team took the Enterprise to the 1984 Consumer Electronics Show. That confidence was rewarded: Atari executives came over and expressed their admiration for the machine. One even admitted it was “the best 8-bit home computer in the world”, remembers David Levy, though with Atari US sales would begin in Q4 1984, said Enterprise Steve Groves spokesman.

Confidence and enthusiasm

And Levy recalls that the mood among the Enterprise development team members was “extremely positive with absolutely enormous enthusiasm, engendered by Robert Madge and his desire to produce the best we possibly could”.

And then the proverbial hit the flan. Six weeks before the Enterprise was due to ship, Elan announced it was changing its name, again. Though the company had been calling itself Elan since mid-1983, it now discovered that “the name Elan has been registered by another company here and overseas”, marketing chief Mike Shirley was forced to admit. The replacement name? Flan. “The change from Elan to Flan was the easiest for us to do,” said Shirley. “Some people have been calling it the Flan computer anyway.”

How the first name change had been announced, in July 1983

You can understand Shirley trying to make light of the change. And ‘Elan’ could easily be changed to ‘Flan’ by erasing the lower bar of the capital E on the litho and screen-printing masters used to stamp the name on the machine and print the box artwork and documentation. It would be less costly than rebranding the machine entirely.

But it quickly became clear that that’s exactly what the company should have done. The company and its computer became, for a month at least, the laughing stock of the UK home computer business as magazine after magazine cracked egg tart gags.

Name change number two

In fact, Elan Digital Systems of Crawley, Surrey had successfully taken out an injunction against Elan Computers in December 1983 to prevent it using the name "Elan" for computer products. The Enterprise maker appealed against the court’s decision but the judgement was allowed to stand. Yet another new name would be required.

Worse, the company also had to put the release of the computer back to September 1984 - a full year after launch - because the machine was taking longer to get right than the development team had expected: specifically the custom Nick and Dave ASICs. Work on these was “going painstakingly”, said Mike Shirley at the time. “We want to produce a trouble-free product and one that is available in enough numbers to satisfy initial demand,” he insisted. “We have talked extensively with the retail trade who would rather see a fully debugged model appear in September in time for the Christmas rush.”

It wouldn’t take that long to come up with a fresh moniker, at least. Taking a cue from the company’s computer, Elan renamed itself Enterprise Computers. Intelligent Software continued to work on EXOS, EXDOS - the Enterprise disk system - and IS Basic. EXOS was updated to version 2.0 in October or November 1984, and reached its (final?) version, 2.1, early in 1985. Industrial designer Geoff Hollington had long since finished off the designs for the plug-on Enterprise memory expansion modules, its software cartridges, and housings for single and twin floppy drive units.

Meanwhile, increasing component costs meant the 64KB model would now cost £228.95, up from £199. The 128KB Enterprise would now not arrive until early 1985. Actually, neither would the 64KB version. By September 1984, Enterprise was telling its retail partners not to expect its first computers until early the following year. “We hope to be out this autumn but we want to make sure that the product is fully debugged first,” company spokeswoman Caroline Jones told Popular Computing Weekly, though it was the same line the firm had trotted out before. “At the moment we cannot say how many machines will be available this Christmas.”

In the same story Bob Denton, head of retail chain Prism, claimed he’d been told the Enterprise would finally be able to be put on sale in January 1985. To be fair, Enterprise does appear to have managed to get some units out before Christmas 1984, but these were just pre-production machines for magazine reviewers and software developers. Shirley admitted full production wouldn’t be reached, in any case, until February 1985. By now Enterprise had changed manufacturing partners, from Welwyn Electronics of Tyneside to GRI Electronics, which was based in Perth, Scotland.

Name change number three

“We intend to sell at least 150,000 machines in the UK in 1985 and are fully geared to produce more if the demand is there,” Enterprise promised potential software developer partners in November 1984. “Our overseas distributor network, already established in over 20 key international markets, will account for a further 100,000 plus machines in 1985.”

The plan would also involve “mounting the most intensive home computer [marketing] campaign ever - to create demand and maintain it”, the company pledged. It said £500,000 would be spent during Q1 on “a tightly targeted TV advertising campaign” featuring a 40-second commercial, “plus continuous double-page colour insertions in the key specialist computer publications”. Some £2 million had been earmarked for advertising throughout 1985, the firm insisted, “the vast majority of which will be spent on TV”.

The ad was an early commercial work by Aardman Animations, best known now for Peter Gabriel’s Sledgehammer music video and the Wallace and Gromit films. When the Enterprise 128 came out, the ad was re-voiced by Matt "Max Headroom" Frewer.

Yet it would be an unimpressive debut. Having taken so long to ship developer machines, at launch there was only the software Intelligent had produced: a set of four games tapes, all written in Basic not machine code. However, faster games were promised to arrive soon after, along with more IS-sourced product, including an assembler/disassembler package, versions of the Lisp and Forth languages, and - inevitably - a chess program. Enterprise said popular software houses Quicksilva and Mikro-Gen had committed themselves to supporting the now not-so-new micro.

Critical acclaim

Meanwhile, reviews written on the back of evaluation time with the late-1984 pre-production machines began to appear.

“With its black, green, blue and red colour scheme, joystick and external heat sink, the machine looks rather futuristic and toy-like at a time when the trend in the home is towards more professional units,” wrote Personal Computer World’s Nick Walker. Stuart Cooke in Personal Computer News (PCN) agreed that it was “extremely futuristic”.

Opening the Enterprise, noted Walker, required the removal of 14 screws and revealed “a single, somewhat cramped motherboard” taking up just two-thirds, perhaps, of the interior area and featuring the Z80A, Nick and Dave chips, and 64KB of DRAM arranged in “a bank of eight 8KB chips”.

The keyboard “is exactly the same type as the much criticised keyboard on the Sinclair QL. Unlike the QL keyboard, this one is actually quite good to use, even if the first touch does make you cringe”, wrote Cooke in PCN.

He also praised the eight function keys, which “can be used with the Shift, Control and Alt keys [so] there are actually 32 available”, as did Walker, who found the keyboard itself “slushy” and in need of the key-press beep sent through the Enterprise’s on-board speaker.

“First impression of the Basic is that it is extremely long winded,” said Cooke. “Most versions of Basic now use abbreviations for their command words. Enterprise, however, has gone back a few years and, just as with Cobol, everything has to be typed out in full - CLS has been replaced with CLEAR SCREEN.” But he admitted that “this does have one good thing going for it: programs are extremely readable”.

Programmer’s micro

Nick Walker liked how, “using the SET statement it is possible to configure a very wide range of machine, video and sound options such as the size of the editor buffer or redefinition of the character set”.

He was also impressed that “it is possible to have a number of [Basic] programs in memory simultaneously, each with its own local variables and line numbers... parameters can be passed from one program to another”.

“The Enterprise is actually a nice machine for programming on,” said Cooke. “Line syntax is checked whenever a key is pressed so you don’t have to wait until a program is run before you find you’ve made an error. Correction of a line is made very simple by the inclusion of a full-screen editor under the control of the joystick. If an error is present on a line, you simply zip the cursor up to the offending error, insert or delete using the keys to the top right of the keyboard and then hit Return.”

The Enterprise diskette drives: designed by Geoff Hollington but never put into mass production

Despite the four-voice power of the sound chip, Dave, the Enterprise didn’t output sound through the connected TV but through its built-in speaker. “This gives a sound quality more reminiscent of the beeper on the Spectrum than a four-channel synthesiser,” grumbled Cooke. “The only way to get decent sound out of it is to plug the output into your hi-fi.” And yet, he said, the stereo output was pumped through the cassette output socket. The result: you can play sound loud, or write data to tape, but not both at the same time - “you will have to keep swapping the plugs at the rear of the machine”.

Nick Walker thought Dave “certainly on a par with the BBC or Commodore 64, the current ‘kings’ of sound”.

Nice touches

“One extremely nice touch,” added Cooke, “is the level meter which appears at the top of the screen when loading [a program from cassette]. This consists of a green and red block. When the green block is lit, the load is going OK; if the red block is lit, your cassette volume needs to be adjusted.”

All good stuff, but out too late. “A year ago, the Enterprise would have stood out as a market leader... At the time it was thought to be the greatest thing to happen since the invention of the microchip...” judged PCN. “Today, with Sinclair, Acorn and Commodore and perhaps MSX all becoming household names, it will probably have a much harder time making an impact.”

PCW agreed, but at least felt able to say “the Enterprise is still ahead of the field in terms of technical specification” and sported a “structured Basic [and a] nicely designed operating system”, but reckoned the competition offered by the QL and the Amstrad CPC 464 would cause it great hardship. “The machine’s idiosyncratic styling and non-standard ports are also drawbacks.”

The delays would come at tremendous cost. Combined with the downturn in the UK home computer market, Enterprise now found it impossible to persuade big name retailers to put its micro on their shelves. Without the high-profile High Street presence this would have ensured, independent retailers were none too keen to sell the Enterprise either.

The cost of the delays

Reducing the price of the 64KB machine to £180 alongside the June 1985 launch of the 128KB model, now priced at £250, didn’t help much, especially when Enterprise’s price list stretched to just 30 software packages. Offering a tool to convert Spectrum Basic programs didn’t win many converts to the Enterprise, either. This down-the-line lack of punter and reseller interest eventually prompted Enterprise’s distributor, Terry Blood Distribution (TBD), to drop the product toward the end of the year.

Enterprise tried to persuade it to reconsider. It promised new kit for 1986, but with sales slow, it wasn’t able to fund the aggressive product development programme it was promising. The Enterprise had built up a fanbase and garnered decent reviews but it was unable to break into the mainstream. Had its computer shipped in 1983, it would have had a tough enough time, but at least the Enterprise was, back then, well specced - “miles ahead of the competition”, PCN had said. However, 18 months to two years on, it was no longer the leap ahead it had once seemed.

During 1986, Enterprise attempted to interest Dixons in an alternative to Amstrad’s PCW8256 word processor, called the PC360. It was unable to persuade the retailer to take the machine.

According to David Levy, Mike Shirley and Deepak Mirpuri made a last-ditch attempt to persuade Greens, a retail chain, to take 20,000 units. Greens’ buyer was interested but only if the machines could be sold to him at a “more aggressive price” than Enterprise had originally offered. Shirley and Mirpuri approached company Chairman Lachu Mahtani, who held the purse strings. Still sure that the Enterprise was a premium product he refused to allow the negotiators to accept the lower unit price.

Missed opportunity

A “fatal” error, says Levy. Mahtani soon relented, but by now Greens’ buyer had lost interest. Had the deal been struck, says Levy, it might have saved the company - or at least kept it going to bring new, more relevanmt products to market. But by June 1986, Enterprise’s endeavours had racked up debts estimated at more than £8m. It could not continue.

The receiver was called in. But with little appetite for the company or its technology - or, indeed, the Z80-based CP/M machine, codenamed Vulcan, it had in the labs as a successor to the Enterprise - there was little choice but to liquidate the business. That was it for the UK, though Enterprise’s partner in Germany continued to offer the machine, peripherals and software into the early 1990s, selling the kit left behind by its liquidated parent. It wasn’t too hard for Enterprise buffs to import machines back into the UK.

The business Enterprise that never made it: Vulcan

Despite Enterprise’s grand plans, an online catalogue of micro serial number suggests fewer than 70,000 Enterprise computers were produced, the vast majority of them - those with five-digit serial numbers - being 128KB machines, most of which went overseas.

After the collapse of Enterprise, Technical Director Robert Madge went on to found Madge Networks, which focused on the development of high-speed networking hardware based on the IBM-developed Token Ring protocol. The new company experienced stratospheric growth during the late 1980s and 1990s on the back of businesses’ growing keenness to connect their personal computers to servers, and to connect premises across telecoms networks using technology like ISDN.

Collapse

Madge Networks proved itself able to compete with Token Ring’s main proponent, IBM. But shifting the company to the US, and a move to rid itself of its Ethernet business, turned out to be the wrong decisions, and Madge Networks declined before eventually going bust in 2003. It lives on now as Madge Ltd. Robert Madge left in 2001. These days he is involved in a number of Malaysian technology ventures.

Enterprise’s failure also hit Intelligent Software hard. IS was one of Enterprise’s biggest creditors and without the prospect of being paid for its work, it collapsed too. David Levy continues to take a close interest in the world’s of chess and machine intelligence, and still writes extensively on the subject and to lead the International Computer Games Association (ICGA).

In 2001, he formed Intelligent Toys to create software able to converse realistically with people - and netted the 2009 Loebner Prize, which judges submitted code on its ability to chatter away like a human.

Geoff Hollington went on to do design work in the hi-tech office furniture sector, and product design for the likes of Kodak and Parker Pens. He currently runs his own agency and is an External Examiner for the Royal College of Art. ®

Special thanks to David Levy and Geoff Hollington for their invaluable insights into the Enterprise story.