Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/10/25/bond_behind_the_scenes/

James Bond doesn't do CGI: Inside 007's amazing real-world action

Invisible Aston? We don't like to talk about it

Posted in Bootnotes, 25th October 2012 10:01 GMT

Bond on Film The Aston Martin; a martini, shaken not stirred; the Walther PPK; cool one-liners. These are the four elements of the James Bond films that have become established in our collective psyche as trademarks of Ian Fleming’s secret agent.

But there’s something else that’s also become a Bond trademark, and transformed what could have been just another literary character into a national figure on par with the NHS and the Queen: palm-sweating, gut-churning, nail-chewing action.

Skydiving into a nose-diving plane, brutal fisticuffs with a bomber on a crane high above an African building site, ripping chunks out of prime St Petersburg real estate using a former Soviet tank in hot pursuit of a fleeing car, skiing off a sheer mountain drop chased by flat-footed goons, also on skis, to deploy a resplendent Union-Jack parachute...

In the 50 years since Dr No, big action scenes have become as central to the Bond legend as the writing through a stick of sticky pink-and-white seaside rock.

But what’s really helped Bond see off Harry Palmer, the Man from UNCLE and Derek Flint, is not the spectacle per se, it’s how – and who – conceived and executed them.

For while lassoing an escaping plane from a helicopter (Licence to Kill), coordinating armies of frogmen fighting to the death (Thunderball), or crashing a speeding London Underground train (Skyfall) might seem merely fantastic, a CGI dream, in fact such scenes are all based on the real-life experience and know-how of those behind them – Bond’s behind-the-scenes men and women.

These are the people The Reg has been speaking to ahead of October’s 50th Anniversary of Dr No and the release of Skyfall.

A fight's not a fight unless it's on a moving train, in Skyfall

Sometimes, they tell us, things have been "too real". For example, parts of the aerial chase sequence from the opening of Octopussy – with Roger Moore in a single-seat jet – were axed because they made early Bond audiences feel nauseous.

Other times, where things have become "too creative", the Bond crew has learned from it: they cite as an example the CGI-tastic Die Another Day Aston Martin, which could turn invisible to the naked eye. Just don't walk into it ...

Ahead of the Dr No anniversary and Skyfall release The Reg spoke to three of the technical whizzes to discover what it took to bring Bond to life. We spoke to Skyfall’s FX supervisor Chris Corbould; Ricou Browning, who was underwater director on both the Oscar-winning Thunderball (the best commercial performer of the all the Bond films) and Never Say Never Again; and John William “Corkey” Fornof – who conceived, designed and personally flew aerial sequences in Moonraker, Octopussy and Licence to Kill.

Skyfall, which premiered on Tuesday at London's Royal Albert Hall, builds on a rich and compelling heritage. Corbould's latest work includes a specially built London Underground train demolishing a station plus a 25-tonne digger with mechanical arm mounted on a train and ripping apart carriages. Both feature in the Skyfall trailer, here. Do pay attention ...

Looking back into the glorious history of the Bond series, ace stunt pilot Fornof pays tribute to first Bond producer Albert R - AKA "Cubby" - Broccoli for creating an environment that made Bond watchable and believable, from Dr No all the way through to Skyfall. Broccoli was co-producer behind all Bonds until Licence to Kill, with his daughter Barbara now running things.

Fornof portrays a man in the mould of John Ford or David Lean, for whom story was king.

"Cubby is the original," Fornof tells The Reg in an interview over the phone from his home in Frisco, Texas. "A tremendous film maker and what we call old-time type of movie maker, that had the imagination to do what you had to do, made sure you had the time and the money to do it. He was into the different departments talking to people making sure they had what he needed."

Fornof has flown aircraft in more than 46 films, including three Bonds.

"Modern movie-makers are more dollar oriented," he says. "I'll do a movie and you have you have a producer come in and say: 'I told you, you had 12 weeks to prep and rehearse and now you have eight.' I was very honoured that at every party he [Cubby] had me sitting at his table. Same with Michael [Wilson producer and screenwriter] and Barbara [Broccoli].

"The most fun is Bond movies - period," he says of his filmmaking career. "The fun is the production meetings where you put all this together."

Ricou Browning hired Thunderball's divers and

directed all underwater fight scenes. Photo: Jordan Klein

Thunderball, by director Terence Young, won Bond its first Oscar for visual effects - Goldfinger won Bond's first ever Oscar, on sound in 1964. Thunderball introduced jet packs, a rocket-firing Aston Martin DB5, and - famously - an epic underwater battle between the frogmen of S.P.E.C.T.R.E. and the US Navy armed with spear guns. The combo was so potent it pushed Thunderball into becoming the most financially successful Bond film - adjusted for inflation – making $599,896,000 in the US according to Box Office Mojo. It's the 27th biggest grossing film ever, with Star Wars at number two and Gone with the Wind number one.

All the underwater sequences were directed by Browning, who recalls how Broccoli and co-producer Harry Saltzman had wanted scenes so realistic they'd been trying to sign up underwater legend Jacques Cousteau.

"They had considered using Cousteau," Browning confesses of his interview meeting with Broccoli and Saltzman. "Cubby Broccoli asked why you, rather than him. I said: 'For one reason. We are phonies. Everything we shoot is phony everything he shoots is live, so we can make it better.' So we got the job."

Fights, chase scenes and disappearing cars

Browning spent "months editing and polishing the Thunderball script. "I created most of the fights," Browning tells us on the phone from his home in Florida. "We just tried to make it look real and for the most part we did. Some of the scenes were a little corny and were edited out. We just did our film."

Broccoli's spirit is alive today, with ideas on bubbling up from all quarters including producer Barbara Broccoli, says Skyfall's Corbould - who has worked on 13 Bond movies.

"The ideas come from any direction - Sam [Mendes, Skyfall director], me the stunt director, the producers ... sometimes it can come from most outlandish areas. Everybody pitches in, the lighting cameraman will come in with a great effect - it's an open forum."

Corbould worked with Mendes to develop the crashing London Underground train scene in the Skyfall trailer, which you'll have seen by now.

"It was an idea I had come up with, with Sam, to have a climatic piece in that part to be dramatic," Corbould tells us. "The scene required a dramatic moment in the chase sequence, when Bond feels he has his villain, and we wanted something that suddenly changes the tables and comes out of the blue."

Die Another Day's invisible Aston: the CGI went too far

Remarkably, Corbould continues, "everything is based in reality".

Never heard of a London Underground train running out of control? It has happened: at Moorgate in 1972, a disaster the left 30 dead and 70 injured.

Corbould makes a valuable point: all the ideas are based on the crew's experience or technical expertise, which is vital because keeping Bond reasonably close to reality helps make 007 feel familiar. Bond doesn't kick film-goers out of their viewing experience; they don't wake up suddenly and say: "Hang on, that's silly and this is just a film."

Not convinced? Corbould has a confession: the Bond crew know when things have gone too far. For example:

"Where we stretched it was on Die Another Day and the invisible car. I wasn't keen on that from day one. We went too far.

"Since then, we have kept things in the realm of reality - but only just," Corbould continues. "The other day I was on a plane and opened a magazine with a pen camera in it and I thought in a Bond film 30 years ago that was in there. This is amazing, because that's where we want to be."

Invisible car technology does exist, it's just too "out there" for audiences to really know much about or to appreciate. Putting it in a Bond film takes Bond a little too close to kicking you out of film-watching mode and into "wait a minute" mode. Mercedes cashed in on the glow of Die Another Day by publicising an invisible B-Class that it had smothered in $263,000-worth of LED mats that made the car "disappear" at a distance by copying the scene around them to fool a watching digital camera.

The catch, apart from the price of the LEDs outstripping the price of the car itself? The fact the power sources, computers and other kit used to power the system added an extra 1,100lb (499kg) to the car's weight, and the result was more semi-visibility than invisibility. The Swedish military has turned to pixels with their local BAE Systems subsidiary to turn a tank invisible, but they're the military. And it's a tank. And it only works in the infrared spectrum.

On the other end of the scale are scenes that are just too lifelike for audiences to handle.

It was Fornof, stunt pilot and consultant on three Bonds, who conceived and executed the flight of the little Bravo Delta jet used in the opening scenes to Roger Moore's Octopussy. The sequence climaxed with the jet flying through an aircraft hangar, barely evading the closing hangar doors. The hangar is then blown apart by a pursuing surface-to-air missile (SAM) before the jet is landed peacefully on a quiet road. With the fuel arrow on empty, Moore taxis up to a petrol station and instructs the startled attendant in this militarised Banana Republic to "fill her up" (evidently this station has jet fuel as well as more normal motor juice).

"If you have a good director he will keep rolling if something is happening," Fornof says. "Some of the things I loved about the Bond movies is they relied on me. As Cubby said: 'These are the shots we need, now you put the magic in them' - that's where the roll in the canyon scene [Octopussy] comes up."

In that opening sequence of Octopussy with the Bravo Delta jet, Fornof is dodging the SAMs through and around the gorges and mesas of Utah. However, some shots were just too realistic for the Bond audience to handle.

"[We were] shooting over Hurricane Mesa with a 1,500 foot drop - there's a forest on top of it. Where the forest ends I pushed negative 2Gs going down. From the camera it was a beautiful shot but we ran it for a test audience during one night, and more than half got sick or were nauseous. People felt like they were being sucked into the scene, which I felt was fantastic but didn't play too well with the audience."

Real life Bond thrills and spills

Many other things you'll have seen in the big, set-piece Bond scenes have been actually done, or have been made to work in real life by those doing them.

The roots of Fornof's Bravo Jet sequence are his own experiences. Buzzing through the hangar came from a sequence he shot for a Toshiba commercial while the idea of landing on a public road originated from an experience Fornof had flying the Bravo Delta when he was forced into an emergency landing in their skies above North Carolina when the small plane suddenly lost oil pressure.

Descending through the cloudbase at 800 feet above hundreds of miles of dense forest, the only thing resembling a landing strip coming into view was a long grey streak of Carolina freeway cutting through the dark green with traffic beetling along in both directions.

"My heart was in my throat – there's no two ways about it," Fornof tells us. "I was going to land someplace and the highway was my runway. Was I scared? Yes, but as a test pilot you lean to stay with it until the situation is over.

"I got in the flow of traffic and almost landed on a moving van. I had enough speed to get in front of the van. So got in front of him and hoped he would slow the traffic down [behind him]. As I came to an offramp, I went down that, to an access road, and rolled into a gas station."

Fornof says the petrol attendant who'd been standing in a doorway walked up to him and asked if it was Candid Camera. Shortly after, the local news showed up.

Fornof's forced landing made the news and inspired the opening of Octopussy

On The Living Daylights, Cubby asked Fornof if it was possible to snatch an airplane out of the air. After three weeks' practice in Miami, Fornof had developed the routine. He worked out how to drop a person by wire from helicopter, a US Coast Guard H-65 Dolphin, onto a Cessna aeroplane, and for that person to loop a cable lasso around the Cessna's tail, so that the chopper could fly off carrying the plane with nose pointing down.

You can - and probably have - debated the strengths and weaknesses of The Living Daylights and Timothy Dalton, but this scene was seminal and showed its influence in the opening of Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight Rises as Batman's nemesis Bane is rescued mid-air and mid-rendition by his henchmen.

Thunderball set the trend for such jaw-droppers. FX man John Stears landed the Oscar but Browning choreographed and directed the sub-aquatic action. The inspiration for this work? Browning was a competitive swimmer with the US air force, who became a scuba diver and who also devised a unique way of breathing underwater – breathing oxygen by drinking what you want from a hose.

This fed into the films: he was cast as The Creature in B-movie classic The Creature from the Black Lagoon. Originally a location scout, he was cast for this style of swimming, considered natural for the beast. Browning then wrote Flipper - the story of a boy who befriends a Dolphin - before landing the job on Thunderball. Browning was spotted by Kevin McClory, who adapted Thunderball and got the diver in front of Broccoli and Salzman for that Cousteau-stopping meeting.

Keeping one foot planted in reality is an important part of Bond as it would be easy nowadays to surrender shooting such scenes to the green screen and CGI. Such digital re-touching technology didn't exist in 1965, though; if it did, Broccoli could have padded the underwater fight scene with hundreds of digitally reproduced frogmen instead of the 60 divers Browning choreographed and staged under the waves.

Mercifully, Bond has remained free of this kind of digital screen-washing, which - done badly - shows the cracks or which can be all-encompassing, as in James Cameron's Avatar. In 1965, the underwater set for Thunderball was built and lowered into position under the Caribbean, including a full-size replica of a Vulcan bomber, the plane carrying the nuclear bomb Emilio Largo steals. The plane was lowered into position 50 feet beneath the waves using a $5,000-a-day crane and fastened to the seabed using weights to prevent powerful currents tearing it away.

Nearly 50 years later on Skyfall, the techies are still keeping it real. The London Underground train was realized in full scale on the Bond Pinewood 007 set in Shepperton using a full-size train consisting of two carriages that were built from scratch and controlled electronically, and sunk into an underground that consisted of the same tanks that had formed the submarine bays for villain Karl Stromberg's submarine-eating supertanker in The Spy Who Loved Me in 1977.

Fornof's petrol-station landing was lined up for shooting

Fornof gives his theory on why Bond's producers pick people over pixels:

"Reading the trade papers I've seen a lot of surveys where people want to see live stuff because they think: 'I can do that on my computer.' I think they want to see things done real."

Skyfall's Bond veteran Corbould, who's seen the rise of CGI, reckons Bond's predilection for big, set pieces done with real people has actually been helped by the rise of digital.

CGI? What of it?

"We were doing GoldenEye at the advent of the CGI wave. I thought we had five years left," Corbould says - he thought it was the end for FX. But what happened was that CGI created more opportunities for live-action work.

"I have 40 people on the FX crew in GoldenEye; by the time I did Die Another Day I was up to 100, because they could show a meteor hitting the ground, and we would do the cars flipping up and exploding." Corboud's mixing up his films, the meteors he mentioned were in Armageddon around the time of GoldenEye, but the principle stands.

So what are the component parts of the Bond set-piece machinery?

Browning (left) with colleague wrangle shark into shot for Thunderball, photo: Jordan Klein

On Thunderball, Ricou hired 60 divers and a crew of 13 recruited from the Miami area, with rehearsals conducted on dry land and, once underwater communicating using nothing more sophisticated than hand signals. Browning had underwater voice communications in time for Never Say Never Again, but this purist reckons through-water comms just made things worse "because everybody wanted to talk".

"Directing underwater is no different to directing topside," he says casually. "The only difference is in the element, so you talk the scene over and rehearse it on dry land or aboard a ship or barge. Then you go under water and shoot the sequence."

Browning says he spent a "solid month" under the waves directing.

"I'd say it was like shooting a horse sequence with groups of cowboys and Indians on different sides. You keep doing it again and again until you get the shot," he says.

The hardest part wasn't communications or air, it was simply fighting the currents and getting the frogmen to meet and fight in the middle once they'd descended. "Once they met you could cut to the individual fights. If somebody shot a spear gun into another person we'd have the spear in the other person and we'd whip the camera on to that person and it would look like they'd been shot."

Browning met Broccoli and the team every four days to discuss progress; he thanks Broccoli for giving him the chance to direct "as I saw fit". "With Thunderball, I wasn't on a tight budget. I was able to take the time to do it correctly," he said.

Sharks were a big feature of Thunderball and Never Say Never Again, creatures considered suitably exotic and sinister to a post-war audience coming out of gloom. Nothing says cruel and ruthless like Largo with his own pet sharks, used for casually offing underperforming henchmen and annoying secret agents.

Browning and team landed the role of taming and handling the sharks, bringing them on to the set and doing what was called for.

"We had to take the time to work with sharks and it tames some time because you can never tell what a shark will do," Browning says.

Sharks where held in underwater pens with ropes around them to make them easier to catch - this was the era before PETA. Come shoot-time, Browning and two fellow fearless divers would snag a shark and hold it by the fins.

"We'd back off if it was too hot," he tells us. The shark was then maneuvered into position and released for it to (hopefully) swim a straight line through the shot into open ocean. Divers would swim down to try to bring the shark back, but mostly it was gone.

Through all this there were just three injuries, one of which befell Browning: in a fight scene he rolled from the upper deck of an underwater wreck onto the lower deck and landed on a spear gun that was leaning up against the hull, with the spear going into Browning by about an inch.

"Went to the hospital and they cut it out," he says. "It wasn't that serious."

For Fornof, the risks came higher and faster. Among Fornof's appearances, you'll see him in The Living Daylights landing a Cessna on top of a moving road tanker (he was the pilot). The challenge: warm temperatures - 118 degrees on the day of the shoot - meant the air was almost too thin to support the plane while travelling as fast as the tanker truck could go. The plane was going so slowly that it was on the verge of a stall throughout, and the oval shape of the tanker meant shifting slipstream, making a landing even harder. Multiple takes were needed.

Lassoing the Cessna from a helicopter in the same film was a sequence that took three weeks to prepare over the skies of Miami. It was such a serious piece of work, Fornof had to meet with US Coast Guard chiefs in Washington DC beforehand. The idea itself held such potential that members of the CIA showed up to film the scene.

"Cubby asked me - can we take an airplane our of the air and I said: 'Yes, we can. I've got a stunt I've been working on for years," Fornof says.

Fornof devised, planned and executed a program to lasso a plane in mid-air using a helicopter

"I wrote a test program - taking our stunt man out to lower him onto the plane's tail on a wire [manoeuvring himself] using sky diving skills. We found he could reach 45 degrees left or right of the helicopter, flaring out to go back and balling himself up to swing out in front. Then we moved to putting the plane in the air. We developed a safety measure for me and the helicopter. The most dangerous part? There was no [para] chute on the wire."

When it came to the aircraft hangar scene, Broccoli and fellow producer Michael Wilson had an idea of what they wanted - Broccoli had wanted the scene four years earlier in Moonraker, but it was dropped during filming thanks to bad weather. Fornof had a meeting with Broccoli and Wilson where the subject under discussion was: can this scene be done and what could be added to complete it? What sealed the deal was Fornof's real-life landing in North Carolina.

"I told them about the landing on the highway," he said.

It was pushing the Delta Bravo jet through the aircraft hangar that held the most risk, though.

Programming... under pressure

Flying in an enclosed area can create pressure feedback: this is where the air pressure tries to equalize on all sides and surfaces of the plane. As the air can’t escape and because the plane is moving, the air is constantly trying to equalise. Trying to compensate with a tug or twist of the joystick in reaction to the pressure is high risk: it produces an oscillation and means you slam the craft into the floor or ceiling as you try to compensate and the oscillation increases.

Fornof ran some calculations on a computer to work out the airspeed at which he could fly through the enclosed space of the hanger without producing an oscillation. Computer said: 156 knots.

“On the last pass I went just above 156 and I got one little bump,” Fornof says.

Flying in enclosed spaces can seriously damage your chances of not crashing

"Cubby told me: 'Do you know why we hire you? We don't hire you to take risks. We hire you because you are known to eliminate the risks'. They hire me to say no when there is no way and to get the shot when it's needed."

Bond’s pilot got an early lesson in the dangers of pressure feedback flying a P51 Mustang at low level in New Orleans, Louisiana.

"My friend said let's fly under the route I [Interstate] 10 bridge and I said that sounded cool. We went fast. The road is six lanes wide, and when I was under bridge l lost 30 knots because the air couldn't go fast enough. It felt great but if the road had been wider there's no telling what could have happened. Being young and stupid taught me a lesson for later."

For Fornof, flying is in his blood; his dad was a US Navy fighter pilot in WWII and then a test pilot and Fornof was always around planes, cleaning his dad’s Grummans, Mustang and Curtis P6. His first aircraft was a Grumman Bearcat, with Fornof flying in airshows before getting into TV.

"I just grew into it," he tells us.

All this has helped equip Fornof to prepare and execute perfect scenes of breath-taking magnitude to the point where the biggest risk in all Fornof's Bond shooting experience has come "on the ground, from other people". Fornof said his most worrying moment was getting jumped by gun-toting Mexican Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) officers in the remote American South West where he'd parked one of the Cessnas at the end of a day's shoot on Licence to Kill. Fornof was wearing a dress - he'd been body-doubling for Bond girl Pam Bouvier (actress Carey Lowell) who, in the story, is the one piloting the Cessna and trying to get wheels down on the tanker truck so that Bond (Timothy Dalton) can jump aboard and scamper up to the cab.

The toughest nut of the Mexican anti-drug posse? A female agent.

"A guy who was 6ft 3inches looked at me - we'd briefed the Mexican DEA ... he came up to me and back-handed me, knocked me up against the side of the plane then rabbit-punched me in the ribs and knocked the wind out of me. They were laughing.

"I stood up and he started speaking English. Everybody knew what we were doing there but this woman agent took the barrel of an AK47 and lifted my dress and with the barrel of that gun started playing with my private parts. I tried to tell them I had papers but when I went to get them, he hit me again."

Having got their jollies the DEA melted into the bush, but that wasn't the last word as an angry Barbara Broccoli jumped on the phone to roast the Mexican authorities.

"That was the biggest danger in my life," Fornof reflects of the encounter.

For Skyfall, the set piece scenes carried their own risks. The London Underground train sequence involved months of sinking the Pinewood set below ground and building a pair of 10-tonne railway cartridges that would hurtle at 30 miles per hour across the set into a tight space and which then had to be brought to s safe stop without anybody getting hurt. All that while getting the shot, and no re-takes.

Mind the gap...

"One of the biggest things we did was the Underground train," says Corbould. "The biggest challenge was the sheer scale and we only really had one go at it - and it had to be at realistic-looking speed."

Set-up was meticulous: the carriages were constructed using a aluminium, fibreglass paneling and polycarbonate to help minimise weight.

"We knew it couldn't veer off the track," Corbould says, so besides a main train track being built that ran atop a set of goal-post-shaped supports, a hidden monorail was added for the purposes of guidance that ran across the entire stage. The speeding train runs along this, then crashes into the main set, which is built of foam bricks eight feet below the Pinewood stage floor in those massive tanks.

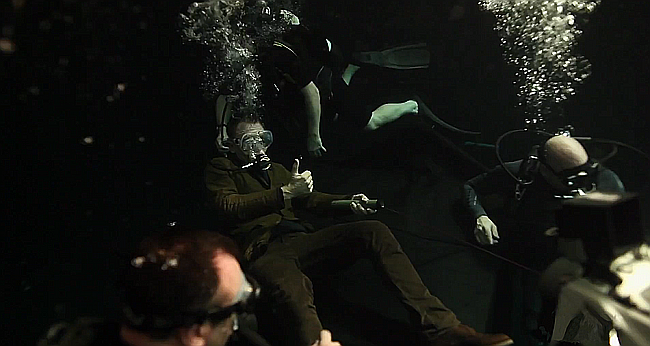

Daniel Craig goes down in Skyfall's underwater shooting, from the Skyfall videoblog

"The second problem was we had to stop the train afterwards, otherwise it would end up in the stage wall. We used a brake system with cap of two tonnes each. We put a series of those in line so it wasn't a dead stop, it was a slowing stop, then 30 tonnes of sandbags to take the real speed out of it."

"In theory we could do it again - but at huge financial cost."

The same might be said of the digger and train sequence. This involved mounting a working, 25-tonne digger on a flatbed carriage moving at 25mph - in the film, the digger's arm is used to span a gap between two separating parts of the train. The digger was wider than the flatbed, so three crushed VWs were installed to act as track for the digger on the carriage. "We had to make sure the digger stayed on the carriage. We built a giant wall to make sure the digger couldn't slide off sideways," Corbould says.

In the 50 years since Dr No, those working on the mechanics of making Bond films have delivered a character that's become as British as the Union Jack, a nice cuppa, and thrashing Johnny Foreigner in the velodrome.

Broccoli and the nation aren't the only fans, as those working on the films have imbibed the spirit and channeled it into the execution of the scenes we know.

Fornof is so passionate he's given ideas to Bonds that he didn't end up filming, thanks to work commitments: the pilotless plane that tumbles over the edge of the cliff at the beginning of GoldenEye – which Pierce Brosnan then skydives into – was a Fornof creation.

"It's all just a matter of gravity," Fornof explains matter-of-factly.

"A person will fall at 120mph. We've done that kind of stuff before. I said why don't you do that, he could go off a cliff. I picked that plane too ... You can put the propeller in reverse - it slows it down."

Fornof's favorite Bond project? Impossible to say.

"I love all of them," the normally plain-talking pilot says, a little romantically. "The're all individual - every one I've done, they all have their stories. I don't know, because they are all like your kids."

How does he rate some of today's Bonds?

"They look good" - but there are some scenes where they could have done a better job on the aerial sequences, Fornof says.

Browning remains a fan, still enjoying Thunderball on TV.

"It was a fun movie to make and watch. I think we did as good a job as we could on Thunderball."

Thanks to Browning, Fornof and Corbould, a literary character from the 1950s has been introduced as a very real and very national character. Most viewers will have first met Bond through the films, without even realizing the books existed, thanks to the bank holiday TV scheduling of the BBC or ITV when growing up or through the box-office assault from the GoldenEye reboot of Bond.

From the martini, shaken not stirred, and the throwaway one-liner ("Shocking, positively shocking"), to the sweat-inducing aerial sequence on the wing or on the crane, we know our man to be cultured, calm and deadly, prevailing over whatever odds the creatives on set throw in his path.

Skyfall producer Barbara Broccoli recently recounted how, growing up with her dad, she too believed Bond was a real person. It wasn't until she was seven that she discovered Bond didn't really exist, she said.

And thanks to the techies behind Bond, the rest of us can still make believe too. ®