This article is more than 1 year old

Supply, demand and a scary mountain of debt: The challenges facing IT as COVID-19 grips the global economy

A lack of liquidity is going to cause complicated problems, analysts warn

Analysis If The Register's readers are anything like its writers, Monday is not the most cheerful morning of the week. We might console ourselves with the thought that if the weekend was a blur, perhaps last week was a dream. Sadly, it was not.

The worst day on financial markets since 1987? Real. The US stopping flights from most of mainland Europe? Real. UK government's £30bn fiscal stimulus to prop up the economy? Real. The Leader of the Free World dumbly in denial over the basic scientific facts of the worst public health crisis in a generation? Opinions vary.

As people rightly focus on their immediate family and friends amid this coronavirus pandemic, and try to do the responsible thing in the face of an unprecedented situation, it's tough to think of what the impact on work might be. Precedents are hardly reassuring. The last time the stock market dropped anything like this much, during the 2008-09 credit cruch, global IT spending fell by $165bn [PDF], a drop of nearly 5 per cent.

Will it be the same this time? Worse or better? It's impossible to tell, but by slashing interest rates to near-zero, central banks around the world are showing how seriously they take the economic fallout from the virus. Wherever you sit in the IT supply chain, whether it is an in-house IT department, a tech reseller, a big vendor or service provider, the impact will come from two directions: supply and demand.

Kit getting scarcer as supply-side complexity hits home

Microsoft has already noted that its personal computing business, including Windows OEM and Surface products, would be hit by manufacturing shortages. Meanwhile, Apple has reportedly told support staff that replacement iPhones for some devices will be in short supply for two to four weeks.

What we're seeing now are signs of the disruption in Asian manufacturing making their way out through supply chains

This morning news arrived that industrial production in China, a global centre for technology manufacturing, fell 13.5 per cent in January-February from the same period a year earlier, the largest fall in 30 years. The effect has already hit UK resellers.

Last week, The Register spoke to a reseller who estimated some orders were facing months of delay as components manufacturers and end product assemblers struggle with the consequences of the outbreak. John White, head of crisis preparation at supply chain risk consultancy S-RM, said this is likely to be the start of several waves of supply chain disruption rippling out of China, South Korea and the rest of the far east.

"It's too early to fully quantify the magnitude of the disruption that our supply chains might experience, but it's probable that what we're seeing is the start of something, much in the same way as we're really seeing the start of what coronavirus looks like in western Europe and the Americas. What we're seeing now are signs of the disruption in Asian manufacturing making their way out through supply chains."

He pointed out that components, end products and source material were mostly all produced in the Chinese regions affected by the virus. Some may be shipped directly to the channel, but components and sub-components are often shipped elsewhere to be assembled in complex extended supply chains. As the inventory unwinds, vendors will start to understand where the problems lie.

Resellers facing 'months' of delays for orders to be fulfilled. IT gathers dust on docks as coronavirus-stricken China goes back to work

READ MOREAlthough the true picture is obscure, doing nothing is not a good option at this stage. White said: "There's a real tendency in the human condition to feel that if you don't know what to do, standing still is going to keep you stable. That is not the case; the situation is evolving around you and it's entirely possible in some situations that doing nothing can be more risky than doing something."

Some IT companies have been quick to act to limit the impact on their operations. Apple has shut down all stores outside China. Microsoft and Amazon advised staff to work from home long before the Trump administration recommended it. A long list of IT companies have cancelled events. But we are just beginning to see the impact the virus itself might have on the ability of the IT supplier community to operate at full capacity.

Nick Wildgoose, senior consultant and CEO of supply chain consultancy Supplien, said companies normally build up inventory in preparation for Chinese New Year, which falls at the end of January. Only as this surplus is consumed will manufacturers understand the full impact, he said.

Crises court clichés, including "cash is king", are likely to be repeated in the coming months. The strain of both hardware and staff shortage on IT suppliers may leave make it difficult for them to fulfil contracts. A lack of cash in the supply market is going to cause problems.

"Remember, at the bottom of most of the supply chains are smaller companies supplying parts or services to manufacturers and cash is essential. For them to weather the downturn, they'll be relying on loans and bank funding," said Wildgoose, who is an advisor to DHL Resilience360 which counts Google and Cisco among its customers.

But even companies surviving supply chain disruption can find themselves at risk. Increasing capacity to take on market share from collapsed rivals can also leave suppliers dangerously short of cash – a problem called "over-trading," Wildgoose said. "They will also need the banks to be accommodating."

In the US, companies are seeing a slowdown and delay in the delivery of tech hardware, said Joe Marion, president of Association of Service and Computer Dealers International, an organisation representing IT resellers But refurbished products were still plentiful and enough to meet demand in the short term, he said. "While this is a difficult time right now for companies that are selling new products, for companies in the secondary market, we're actually seeing a little bit of an uptick," he said.

Resellers can convince clients to switch to refurbished products or agree to short term rental during a period of constrained supply, he said. Also, on the supply side, is the prospect of a reduced level of support from IT services suppliers and software companies as staffing levels fall when employees become ill or self-isolate. In a worrying sign, BT Group CEO Philip Jansen confirmed he been diagnosed with COVID-19 just days after meeting bosses from Vodafone UK, Three, O2 and UK government officials.

Demand dries up

With the virus's early impact hitting the centre for global technology manufacturing in China and the far East, and the prospect of a large chunk of the workforce off sick in a short period, concerns about supply shortages are at the forefront of the tech industry's mind. But a bigger problem is lurking in the wings. As sectors of the world's largest economies stop traveling and venturing out in significant numbers, demand for technology could also collapse, far offsetting any supply constraints.

Travel bans and public movement lockdowns are hitting airlines, hotels, travel companies, conference venues, and retailers around the world. In a sign of the severity of the situation, Peter Norris, the chairman of Virgin Atlantic, is calling for a £7.5bn bail-out of the UK's airline industries to avert a catastrophe that would wipe out tens of thousands of jobs, according to Sky News.

Don’t look now! The debt lurking in balance sheets

The fear then is that a lack of liquidity leads to another credit crunch. Instead of the 2008-09 crash warning companies off debt, they have become addicted to cheap interest rates and built up a mountain of it. Global corporate debt outside financial services mushroomed to $75 trillion at the end of 2019, up from $48 trillion at the end of 2009, according to the Institute of International Finance. Tech companies are already responding.

Last week, Micron Technology drew down $2.5bn under its revolving credit facility to increase its cash position. While fears of companies' ability to service this debt had focused on the prospect of rising interest rates, now commentators are looking at company cash flow and revenue as the trigger for a cascade of defaults.

The world's industries react

That's one of the reasons stock markets have fallen around the world, Jerry Flum, CEO of CreditRiskMonitor, a financial risk advisory firm, told The Register. "The debt risk is greater than it's ever been. What this virus has done is come into this highly unstable situation of corporate borrowing all over the world. [The markets] tripped on a pebble; the pebble is the virus."

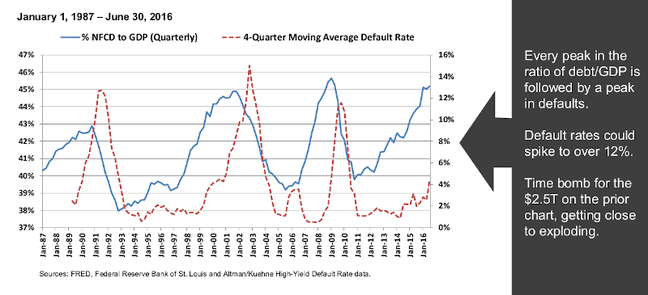

This slide is from 2017, but it illustrates the problem of every peak in corporate debt being followed by a spike in defaults. Copyright CreditRiskMonitor

If a central bank's decision to cut interest rates fails to stimulate demand, companies will try to do so by reducing prices, further eroding margins and putting cashflow and the ability to service debt at risk. "The real denominator, the thing that really is going to tell who the survivors are going to be is the amount of debt on your balance sheet," he said. CreditRiskMonitor's research suggests every peak in corporate debt is followed by a spike in defaults (see graph above) sooner or later.

Flum is not alone in his analysis. "This certainly is another match being lit [near] the bonfire of corporate debt liabilities," Simon MacAdam, global economist at Capital Economics told CNN at the weekend.

Others are a little more sanguine. William Kidd, director at Omdia, a technology research firm, said the impact of COVID-19 was "a very large issue for the companies when you combine both the supply side and the demand side effects." Pressed to forecast revenue falls across the technology sector, Kidd said there would be an average of a 10 per cent revenue drop.

Numbers not yet going south

But overall, he claimed the technology sector is in a good position. "Following the 2008-09 crisis, the tech sector had very significant declines in terms of shipment of semiconductors, as well as electronic devices. They were much larger than 10 per cent. But, in terms of the viability or company health, that was very strong."

Number forecasters are suggesting a fall in growth rather than a drop in overall demand for tech products and services. Last week, IDC cut its forecast growth for ICT spending in Europe during 2020 from 2.8 per cent to 1.4 per cent. But the situation is still nigh on impossible to predict as the spread of the virus in the US – the crucible of the technology industry – is unknown.

As of last week, the total number of people who had been tested in the US was around 11,000, whereas South Korea, for example, had tested around 230,000 people. Last night, Brett Giroir, US assistant health secretary, said there would be approximately 1.9 million tests rolled out to laboratories this week.

Five million tests have been promised in the next month.

Economist folklore says when America sneezes, the world catches a cold. We could be about to find out what happens when the world's largest economy gets a nasty dry cough. ®