This article is more than 1 year old

Come kneel with us at UK's Cathedral, er, Oil Rig of the Canal: Engineering masterpiece Anderton Boat Lift

Give a Cheshire cheers to a true waterway wonder

Geek's Guide To Britain One of the Seven Wonders of the British Waterways, the Anderton Boat Lift, near the Cheshire town of Northwich, is a perfect example of the rise, fall and reinvention of Britain's Victorian industrial heritage.

When it first opened in 1875, the lift – referred to by some imaginative souls as the Cathedral of the Canals and the Eiffel Tower of the Waterways - represented the very finest in Victorian civil engineering, an elegantly simple yet ingenious answer to a pressing engineering question. There followed many years of technical and commercial success before a gradual and near terminal decline set in followed by rescue from the metaphorical scrapheap and restoration to its former glory.

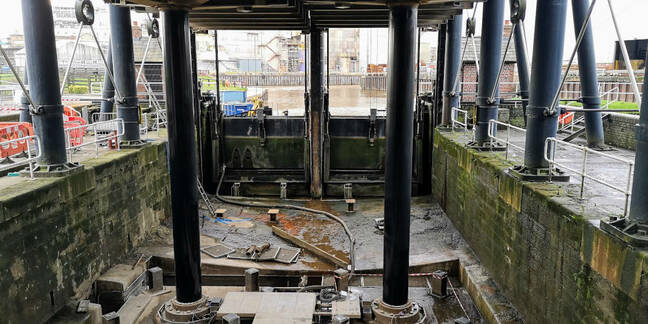

The lift originally stood on an island but subsidence required the area beneath the aqueduct be infilled. All pics: Alun Taylor

The story of the Anderton Boat Lift begins with the rapid expansion of the Cheshire salt industry in the early eighteenth century and the development of the Staffordshire pottery industry. To facilitate the transport of salt and pottery to the docks at Liverpool and to move raw materials the other way, two navigable waterways had developed.

The River Weaver had become the Weaver Navigation by an Act of Parliament of 1721 and linked Winsford with the River Mersey at Runcorn while an Act of 1766 established the Trent & Mersey Canal which linked the towns of what was becoming known as The Potteries with the Bridgewater Canal and, again, the Mersey.

By luck rather than judgement, the two increasingly busy waterways almost came together at the village of Anderton. Almost. There was a slight issue of a 400ft (122m) horizontal and 50ft (15m) vertical mismatch. In 1793 the Anderton Basin was excavated to allow for the manual transfer of goods between the Weaver and the Trent & Mersey making the area a focus for warehousing and industry.

By the late 1860s, it was becoming obvious that a more efficient system for moving goods between the Weaver and the Trent & Mersey was required: one which enabled fully laden boats to be transferred between the two waterways.

Enter the Anderton Boat Lift

Why a lift? In short, the other two options – a system of locks or an incline – wouldn't easily fit into the space between the Anderton Basin and the Trent & Mersey canal. For example, the Bingley Five Rise Locks on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal achieved a total lift of 60ft (18m) but over a length of roughly 350ft (106m).

The water loss inherent in a lock system – the Trent & Mersey was known as a shallow canal, especially during the summer – and the time it would take to transfer boats were other causes for concern.

The boat lift was the brainchild of the Weaver Navigation's chief engineer, Sir Edward Leader Williams (who later went on to mastermind the Manchester Ship Canal and the Barton Swing Aqueduct) and civil engineer Edwin Clark, whose design for a hydraulic ship lift at the Royal Victoria Dock in London Leader Williams may have been familiar with. The basic idea, then, was Leader Williams', while the detailed work was down to Clark.

The idea of a lift was not that revolutionary. Records show that several experimental canal boat lifts had been constructed in Britain between 1790 and 1820.

Robert Weldon designed and tested a boat lift on the Shropshire Canal at Oakengates while engineers Exuperius Pickering and Edward Roland conducted similar trails at Frankton Junction on the Ellesmere Canal. James Fussell designed a lift with two counterbalanced caissons for the Dorset & Somerset Canal at Barrow Hill – though, like Robert Woodhouse's lift on the Worcester & Birmingham Canal at Tardebigge, it never progressed beyond the trial stage.

In the 1830s James Green built a successful set of seven stone-built counterbalanced boat lifts based on Fussell's designs on the Grand Western Canal between Taunton and Lowdwells in Somerset. They apparently worked reliably for 30 years until the demise of the canal in 1867.

Clark's final proposal was a masterpiece of both elegance and simplicity. A 50ft tall (15.2m) cast-iron frame would be built on the island in the Anderton Basin to hold the guide rails and access platforms for two wrought iron caissons. Each caisson would be 75-ft (23m) long and 15-ft 6-inches (4.7m) wide and capable of holding two 72ft (22m) long narrowboats (each roughly 6ft or 2m wide) or one larger barge of 13-ft (4m) width.

Each water-filled caisson would weigh 252 tons with or without barges in it (thanks to the equilibrium of liquids) and would be supported by a 3ft (0.9m) diameter hydraulic ram. The cylinders for the rams, sunk vertically to a depth of 50ft (15m) below the bed of the lift chamber, were connected by a 5-inch (127mm) pipe with an isolator valve.

Linking the top of the lift with the Trent & Mersey would be cast-iron aqueduct measuring 162ft and 6 inches (49.5m) long, 34ft and 6 inches (10.5m) wide and 8ft and 6 inches (2.6m) deep. As the two caissons would counterbalance each other the only external hydraulic pressure was in the form of an accumulator and a 10 horsepower (7.5kW) steam engine.

The system was designed so that when boats were loaded into the caissons and the sluice gates closed there would be a 6-inch difference between the water levels in the lower and upper caissons. That 6-inch difference makes the upper caisson some 15 tons heavier.

The isolating valve connecting the two water-filled hydraulic rams would then be opened and the heavier, upper caisson would descend and the lighter, lower one, ascend. Water levels were then adjusted to match the canal and river respectively and the sluice gates opened.

The accumulator was used to push the caissons the last few feet into their final resting places or if just one caisson needed to be moved independently. The caisson transit took 3 minutes and boats could make the complete trip from one waterway to the other in between 10 and 12 minutes. If a single caisson was raised by the accumulator, the transit time was around 30 minutes.

The Anderton Boat Lift was formally opened to toll-paying commercial traffic on the 26th of July, 1875 and proved to be quite the money-spinner for the Weaver Navigation Trust. Just as well as the total cost had risen from a planned £28,420 to £48,428 or £4.6m at today's prices. The tonnage of goods moved through the lift rose from 31,000 tons in 1876 to 67,000 tons in 1885 to 213,000 tons in 1914.

A corrosive issue

Unfortunately, there was a cancer eating away at the lift's hydraulics from day one. The polluted water that filled the hydraulic rams to a pressure of between 550 and 670 lbs per square inch (38-46 bar) was eating away at the pistons. Attempts to solve the problem by hammering copper strips into the damaged sections of the cylinders actually made matters worse thanks to electrolytic corrosion.

Converting the hydraulic system to use distilled water in 1897 slowed but did not solve the problem. Essential maintenance began to close to lift for weeks at a time.

By 1904 things had become so bad that the then chief engineer, Colonel JA Saner wrote a report recommending that the lift be converted to electrical operation. In 1906 the trustees bowed to the inevitable and gave Saner the go-ahead. This is why the Anderton Boat Lift looks like two structures, one inside the other. It is.

Saner's plan was brutally simple. Build a steel A-frame gantry around the existing structure and use it to support a machine deck which would house the headgear for an electrically powered winch system utilising an array of thirty-six 14-ton cast-iron counterweights and two 30 horsepower (22.3kW) motors, one per caisson.

Despite the complexity of the job, Saner accomplished it with the absolute minimum of interference to lift traffic. During the installation of the new system, the lift was only fully closed for three periods which amounted to only 39 days between April 1906 and July 1908, when the electrified lift was officially opened.

Saner, a stickler for detail, was fully aware that while the corrosive nature of the water on the Anderton basin was no longer an issue, the corrosive quality of the air thanks to all the local industrial activity, was. Annual repainting was required and was likely carried out until Saner retired in 1934 after 50 years service to the Weaver Navigation. Thereafter it seems that things began to slip.

Between Sander's retirement and the mid-1950s, the Anderton Boat Lift plodded along with only the odd mishap but with maintenance increasingly reduced to fixing what broke. An inspection in 1965 found many serious faults mostly related to badly corroded steelwork. Indeed, it was the 1908 steelwork rather than the 1875 cast-iron that gave the most cause for concern. A further inspection in 1972 anticipated a possible collapse unless urgent work was carried out.

The rapid decline in commercial canal traffic in the post-war period removed the financial impetus for such work and so the Anderton Boat Lift continued to deteriorate. On April 14th 1981 an accident occurred when a caisson lost water thanks to an improperly closed sluice gate causing it to rise too rapidly and collide with the aqueduct structure, resulting in not insignificant damage. Nobody was injured (indeed, throughout the lift's history nobody was seriously injured either building or using it) but the writing was on the wall.

During a routine inspection after the accident, a worker accidentally poked his finger through one of the iron girders at the top of the structure! In the autumn of 1983, the Anderton Boat Lift was closed permanently after 108 years of use.

Rust in peace? No thanks

Thankfully the structure had been listed by English Heritage in 1976 giving it some statutory protection as it sat rusting and largely forgotten. In 1987 the cast-iron gears and electrical motors were removed from the engine deck and along with the counterweights, stacked along the banks of the Weaver. The A-frame structure was considered in danger of collapse if they were left in place.

Forgotten? By the public maybe, but not by British Waterways or a determined band of canal enthusiasts who by the late 1980s were considering a number of options for the lift ranging from maintaining it as a static display to a full restoration with both caissons operational. In November 1994 a detailed restoration plan was drawn up with a price tag of £7 million.

Thanks to over £430,000 in private donations, a £3.3m grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, funding from numerous other interested charitable bodies and the rapidly increasing number of leisure craft using the canal system the money was raised and work on the restoration began in March 2000. The lift was formally reopened on March 26th 2002.

The restored lift is very much a distinct third incarnation. The caissons are once again powered hydraulically but this time by an electrically-powered, oil-filled system rather than the original water-filled hydraulics. The dry dock has been retained from the 1908 redevelopment while the gearing and motors have been refitted to the machine deck. They are only for display, however. The counterweights were not refitted and now form a maze outside the visitor's centre.

The new fully pumped hydraulic control system was designed and installed by Fairfield Control Systems, the same company responsible for the hydraulic controls at the Falkirk Wheel. Unlike the 1875 hydraulic system, it does not depend on the differential pressure between the two caissons.

When both caissons have an equal amount of water in them, oil is pumped from one side of the system to the other by two 45kW electric pumps. Smaller 18.5kW pumps can be used to overcome natural leakage within the system and maintain the caisson positions. When raising a single caisson two 90kW fixed displacement pumps are used.

Control of the lift now takes place via a fully computerised system in the visitor's centre rendering the control cabin atop the lift obsolete. The interior has been maintained in the same state it was during the final days of electrical operation.

This new design was in many ways the perfect solution. It maintains much of the design purity of the original (better appreciated without the counterweights and their steel cables obscuring the 1875 ironwork) and lets visitors see the way the lift evolved over the years. And all the while maintaining the lift as fully functional.

What to expect

Visiting the Anderton Boat Lift today one is struck by the difference between the perfectly landscaped and presented area around the lift and visitors centre on the northern bank of the Weaver and the industrial harshness of the now Tata-owned chemical plant on the southern bank.

Photographs from the early 1990s clearly show the degree to which industrial activity on the north bank had declined from its peak in the early 20th century, leaving only an unkempt scrubland. The contraction of industrial activity on the south bank over the last fifty years is also clearly evident.

Of course, if the entire site were still a blighted industrial wasteland it would not be a pleasant place to visit. And pleasant it undoubtedly is. I was given a guided tour by one of the site's staff, essentially the same as the "Walking The Lift" tours that the general public can buy tickets for.

It allows you to get up close and personal with the structure and to get a first-hand idea of how badly the structure must have decayed before restoration took place. Large sections of the cast-iron beams that support the upper part of the 1875 structure had to be patched with welded plates which in places outnumber the original, riveted sections.

When I visited the two caissons were both at half-mast for maintenance, a position that highlighted the visual similarities with the Barton Swing Aqueduct. Even if you didn't know that Leader Williams had had a hand in building both, you would still suspect a pretty fundamental connection.

As a combination of a working industrial artefact still fulfilling its original purpose and an accessible heritage monument to a bygone era, I can't think of anything that trumps the Anderton Boat Lift. It's well worth a visit.

Incidentally, should you visit the Anderton Boat Lift and want to seek out similar constructions, Edwin Clark went on to design another, larger boat lift on the Neufosse Canal at Les Fontinettes in northern France. Clark's company also went on to design and build four boat lifts on the Canal du Centre at La Louviere in Belgium which only recently retired from active commercial use.

The Anderton Boat Lift

GPS: 53.272739, -2.530480

Address: Anderton Boat Lift Lift Lane, Anderton, Northwich, Cheshire, CW9 6FW

Getting there

The Anderton Boat Lift Visitors Centre is open from 9.30 am to 4 pm every Saturday and Sunday. Entry is free though there is a charge to park (normally £2.80 for three hours but both ticket machines were switched off when I visited).

If you want to get up onto the lift's superstructure you will need to book onto one of the "Walking The Lift" guided tours. These cost £5 per person and run on selected dates in August, September and October. Details are on the website. I was told that the team are more than happy to accommodate special guided tours for groups.

You can travel through the boat lift on The Edwin Clark for £8.50 (short cruise) or £12.50 (long cruise). Trips run every day from Saturday 21st of March to Sunday 1st of November. It is recommended that you book two weeks in advance. Again, details are on the website.

The Visitors Centre includes a gift shop, a rather decent cafe, toilets and information displays about the lift that should satisfy most knowledge levels and ages. There is outdoor seating in the grounds of the Visitor Centre too.

By car: Follow signs for Anderton and then the brown tourist information signs to the Anderton Boat Lift car park.

By train: The nearest train station is Northwich. For there Anderton is a 35-minute bus ride or a 2 mile, 40-minute walk, most of it through the Anderton Nature Reserve that abuts the Visitors Centre.

Further reading: A Guide to The Anderton Boat Lift by David Carden, ISBN 0953302865.

The Seven Wonders of the Inland Waterways by John Suggitt, ISBN 1916012515.