This article is more than 1 year old

What if everyone just said 'Nah' to tracking?

Privacy is nearly dead, but we're not even close to getting over it

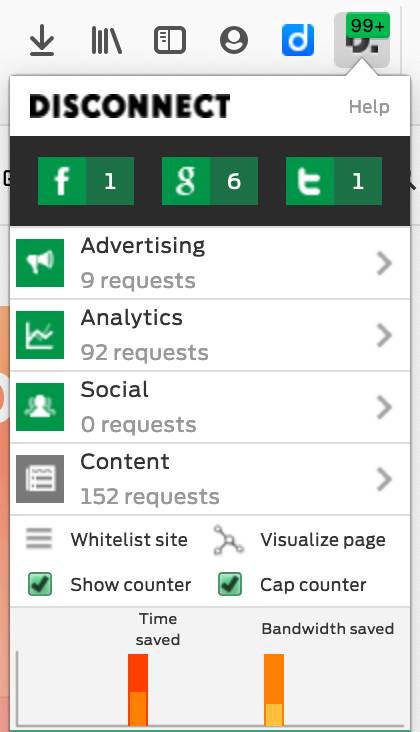

Column Sitting quietly in the upper corner of my browser's address bar, a counter rises as Disconnect thwarts requests to track me. Visiting well-behaved sites (such as El Reg), those numbers tick up more slowly.

On others - I won't name and shame, except to note that they're a bit tired - the counter ticks up and over the two digits it can display in the icon. Of this, it's reported that nine were requests for advertising, while more than ninety tried to send data off to "analytics" sites. You know the type: the profilers, the data harvesters, the location-stealers. Big data empire builders who maintain hundreds of millions of individual profiles - then leave them around for anyone to copy.

Disconnect does what it can, but at best it provides an incomplete shield. So much tracking has been embedded into nearly every connected product and service that Eric Schmidt's hideous pronouncement "privacy is dead, get over it," sounds like incitement to malice - and an understatement of what would eventually come. A world without privacy isn't only a world where it's hard to find the space to act without fear; it turns out that - paradoxically - it's also less secure.

The smartphone, indispensable and irreplaceable, has also become a massive security risk, because apps collect data, profile their users, then sell those user profiles. Cross-referencing multiple data sets, those profiles identify all of us, precisely. Late last year, the New York Times ran its own analytics - on a leak of mobile location data - de-anonymising it, then identifying government officials. While this seems a very big deal when Secret Service agents and US Defense Department officials pop up under a big data microscope, we'd be foolish to ignore the impact it has on all of us. Everyone in proximity to anyone "of interest" now takes a risk.

At the beginning of January, California's new Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) went into effect. We can all request a copy of our data from the companies that hoover it up, and can even ask nicely that it not be sold on. Hooray. Both CCPA and the EU's hasn't-worked-out-as-planned General Data Protection Regulation seek to tame the data once it has been collected. Yet each overlooks a basic fact: collection happens to be where the damage gets done. Passing laws to do something about it after the fact, while well-intentioned, does nothing to prevent the injury.

It all reminds me too much of my favourite Monty Python skit, "How Not To Be Seen," wherein various individuals (who can not be seen by the camera) are identified - then bombed to bits. Shouting our locations via our apps, we effectively paint huge bullseyes on our backsides, begging to be targets.

Track-me-not

What if we just say no?

This refusal runs counter to an economic model that insists that visiting a website grants it rights to conduct a sort of data mugging, where all one's valuables get spirited away, to be sold on through a data fence to the highest bidder. If we fight these robbers, and defend our property, well then, we're told that the economic basis for the web would simply implode. Advertisers would withdraw their ads, and economic catastrophe would result.

Poppycock. Advertisers need eyeballs, and they'll buy them, even if they can only guess that someone reading El Reg might be into IT. The finer gradations of profiling – beyond common sense – and rule of thumb offer too little value at too high a price.

Knowing everything about a user does not make them a better customer. Offering a better product and better service at a better price - that might. And you don't need analytics to tell you that. ®