This article is more than 1 year old

I spy a secret High Court: We're no 'star chamber', it says in 4-year report

Investigatory Powers Tribunal puts pen to *redacted*

The only court where you may appeal our spies' illegal activities in the UK has finally published a report covering its activities from 2011-2015, defending itself against accusations that it is a “star chamber” which “always meets in secret and never rules in favour of complainants”.

The Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT), which sits for an unknown and unknowable number of secret hearings every year, was established by Section 65 of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA).

Obliged to hear two particular complaints against the intelligence agents, the IPT receives applications from those who believe they have been “the victim of unlawful interference by public authorities using covert techniques regulated under RIPA,” and those who believe they have been “the victim of a Human Rights violation” conducted by the spooks.

Its creation followed the passing of the Human Rights Act 1998, after which it became necessary to ensure that the UK met Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) which states:

Everyone whose rights and freedoms as set forth in this Convention are violated shall have an effective remedy before a national authority notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.

Unlike the “star chamber” to which the report's author referred — an English court which in the 16th and 17th centuries became a byword for the monarchs' secretive abuse of the legal process to prosecute their own enemies — the IPT's hearings are increasingly open, through far from completely. That it indeed validates the Article 13 requirement was upheld by the Strasburg court in the case of Kennedy v The United Kingdom (2010).

While holding hearings in camera is not unheard of in English courts — especially for the purposes of protecting children — the practice of protecting the intelligence agencies from the attention which attends public trials has some under criticism following the disclosures made by rogue NSA sysadmin Edward Snowden, which revealed illegal activities had taken place under the existing regime.

Introducing the 52-page report (PDF), the tribunal's president, High Court judge Sir Michael Burton, acknowledged that the last two years had been quite busy for his team, due in part “to the recent well publicised and unauthorised Snowden disclosure and in part due to the greater interest in the Tribunal by Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) such as Liberty, Privacy International and Amnesty International”.

Not a single complaint brought to the tribunal regarding the security and intelligence agencies' surveillance activities had been upheld until supported by the documents leaked by Edward Snowden in 2013. Since that date, the report notes the number of complaints had steadily risen, though an unexplained reversal of the decline in the number of applications to the tribunal is already visible from 2008 onwards.

Initially slated for 2015, the tribunal's first annual report — which is published voluntarily, rather than as a result of any statutory obligation — was scrapped as the body was swept by more applications than expected. Among this uptick in complaints were the 663 applications brought as a result of Privacy International's campaign to solicit applications against GCHQ after the agency had been found to have illegally shared information with the NSA.

Many such hearings have historically been held in private, however over the last 18 months the tribunal has held “a considerable number” of public hearings and “delivered eight reasoned judgments in open.”

According to Sir Michael:

This has been achieved not, I believe, at the expense of any risk to national security, but by so far as possible developing the device of hearing cases on the basis of "assumed facts". This means that without making any decision in the first instance as to whether the facts alleged by complainants are true, where appropriate the Tribunal invites the parties to formulate and agree issues of law for the Tribunal to decide upon the assumption that they are true. This has enabled hearings to take place in public with full adversarial argument as to whether, assuming the facts, any such conduct as a claimant alleged to have occurred, by, for example, the SIAs, would have been lawful. Following this, closed hearings may be held in private ("closed"), when the legal conclusions of the Tribunal can be applied to the facts that it determines to be true.In this respect we are in a better position even than the Commissioners, who have the right and duty to exercise far more sweeping investigations, but do not have the benefit of adversarial argument to resolve these issues. It also goes a long way to meeting what has been rightly been described by the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (Report, 2015) as “the practical difficulties of making a case that will be heard in secret”. In this respect I believe we are pioneers, and a number of other similar bodies in other countries have expressed interest in following our lead.

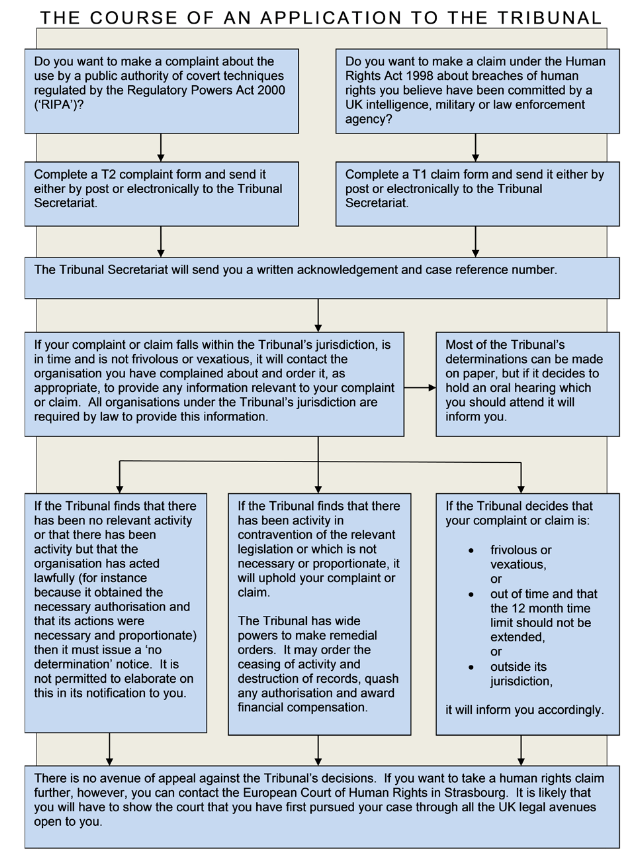

The report also published a flow-chart regarding the course of an application to the tribunal:

The tribunal considers material about secret interception and surveillance operations — which includes “material of the highest security classification which, if disclosed, could harm national security and law enforcement operations” which “if they are to be used effectively… must be secret”.

As such, there are no figures given on the number of closed hearings at the tribunal during this period; it claims it is prevented from giving them by its governing rules. However, an increasing number of open hearings have been held and resulted in the publication of internal manuals regarding the spooks' access to Britons' personal data.

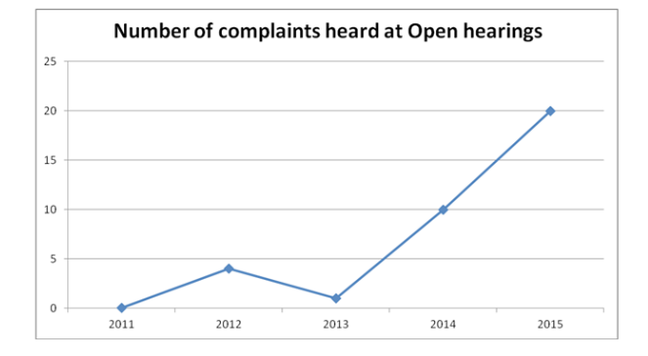

A graph published in the report related to the number of complaints which were heard in open hearings, though this figure also included single complaints that were heard over several hearings, for instance while 20 complaints were heard in open court in 2015, there were only 15 sittings in open court during that period.

As Burton wrote, there have been a number of cases which the IPT has brought which have led "to the disclosure of rules and procedures under which the [Security and Intelligence Agencies] have operated, which were not previously in the public domain".

"I believe that the Tribunal's methods generally work well," added Burton, "I trust they have gained the confidence of those applying to us, and that they are recognised as fair and sensible by those organizations we investigate as a result of the applications made to us." ®