This article is more than 1 year old

Kobayashi Maru gets real: VR and AR in meatspace today

Outside the Silicon Valley hype cycle

Three years ago few people other than hardcore gamers and those working in specialist industrial fields were still talking about VR.

It was a gimmicky technology cursed by the “P” word (“potential”) and huge, ungainly headsets that generated a flurry of interest in the late 1990s that quickly evaporated.

Today, it’s big news. Arguably much of the resurgence in interest is down to Oculus, the company that surprised everyone in 2012 with a fabulously successful Kickstarter campaign to build its Rift VR headset – or using the modern parlance, head-mounted display (HMD) – for just $300.

By the time Oculus had released a second, more compact version of Rift to developers in July 2014, the company had been acquired by Facebook for the previously inconceivable sum of $2bn. The consumer version was duly announced last summer, and when pre-orders opened in January this year at $599 per unit, all hell broke loose. For less than the price of a top-end smartphone, gamers can now experience 360-degree 3D immersive gameplay via a high-resolution, low-latency VR HMD that not so long ago would have cost 20 times as much and weighed more than your own head.

The Oculus Rift is not a self-contained system: it’s 3D display device for hooking up to a Windows PC, and a reasonably beefy one at that. VR of this type demands a recent processor, a powerful graphics card and lots of memory.

This isn’t to say that the new wave of VR is restricted to the gaming elite. Samsung partnered with Oculus in 2014 to create the £96 Gear VR, a lightweight HMD designed to be driven by a Galaxy smartphone running Android. The phone itself slots into the back, providing the necessary binocular video as well as the computing platform.

Paring this concept down even further, Google conceived an ultra-lo-fi HMD constructed from pizza-box cardboard, selling for under £10 or, if you have recently had a pizza delivered, for nothing if you download the free cut-out template and have some velcro, capacitive tape and a pair of 45mm focal length lenses lying about. With an Android or iOS smartphone in the back running a compatible app, for most people Google Cardboard will be their first experience of binocular 3D VR.

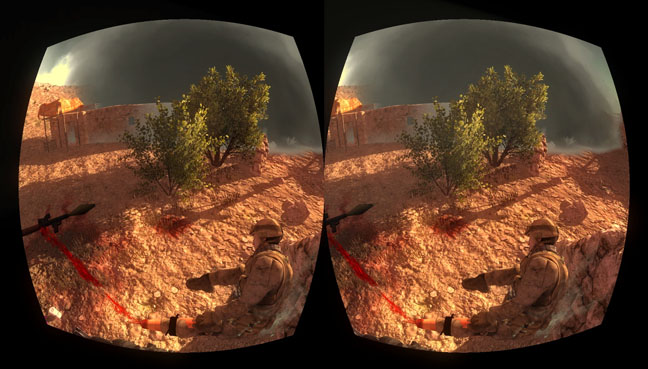

Field medics learn how to work under shifting battle conditions in Plextek’s VR training environment for the DSTL

It’s an experience that sells VR to the masses: indeed, Google claims that more than five million people own Cardboard viewers and over 1,000 apps have been created for them. Even if you dismiss it as a short-term consumer electronics fad, modern VR is inexpensive and accessible – two accusations you could never make about 3D TV.

Nor should VR be seen principally as gaming tech. “VR has a range of fascinating applications that range beyond the entertainment industry,” says Robert McFarlane, head of labs at digital agency Head, citing examples such as visualising real time data or winning new business though immersive media. “VR has already started seeping into the way medical professionals are trained, and how they diagnose and treat their patients.”

The South London and Maudsley (SLaM) NHS Foundation Trust, whose Institute of Psychiatry is ranked world number one for its academic citations, is beginning to make use of VR in the treatment of phobias. In a recent project prototype using last year’s Oculus Rift HMD, children suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder were helped to overcome their repulsion of public toilets by putting them in a controllable virtual washroom while they remained physically in a safe and comfortable environment, such as their own home. The children could incrementally control the virtual toilet’s cleanliness, or lack thereof, while wearable devices monitored their temperature, heart rate and stress level.

If it sounds a bit like a game, everyone working on the SlaM project is well aware of it. Bleddyn Rees, digital health consultant for Osborne Clarke, noted: “There is an increasing interest in taking gaming learning into clinical treatment.” Indeed, SLaM’s chief information officer, Stephen Doherty, has a background at Sony Computer Entertainment Europe. Kumar Jacob, chief executive of Mindware Ventures, said the SLaM prototype took just eight weeks to develop and that funding is being sought for a bigger trial: “VR can be used in the broader sense for cognitive behaviour therapy and phobias: it has a lot of potential.”

Medical training is another emerging application for VR but not necessarily in the way you might expect. The UK Government’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) is using VR to teach soldiers how to assist wounded comrades in the field.

Where previously the trainees might practise bandaging up a volunteer in a spare office, the system, developed by Plextek Consulting, immerses them in a 360-degree virtual war zone of up to three square miles in scope. As part of a squadron of up to eight, some of whom can be accessing the system from other physical locations, they hear an explosion in the distance, negotiate how to approach the site and soon discover a victim who has lost part of a limb. The trainees must then determine how to triage the patient according to medical procedure, apply a tourniquet and call a helicopter to evacuate.

Grimly evocative of Star Trek’s Kobayashi Maru test, the system allows trainers to insert complications along the way, such as unexpected gunfire, smoke limiting visibility and sudden changes in the patient’s condition, which will influence the trainees’ responses and affect the eventual outcome. As Collette Johnson of Plextek explains: “When you do something wrong, the scenario changes and follows through according to the decisions you made.”

The system makes use of Oculus rift HMDs but Johnson is keen to develop it further for £689 HTC Vive headset, calling it “a game changer for real-world applications outside gaming, such as disaster relief, by allowing room for movement and enhanced graphic quality.”

Less surprisingly, heavy industry has also warmed to the opportunities that VR presents, not least because it has been using 3D design tools for decades.

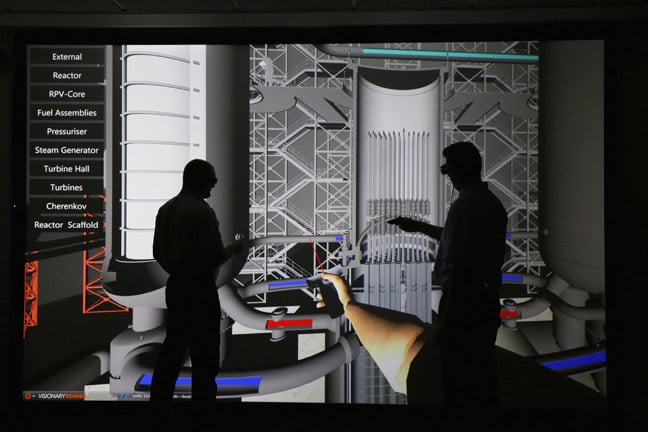

University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) has been working with the likes of Caterpillar, Boeing, Rolls-Royce, BAE Systems and Airbus, while its sister branch Nuclear AMRC focuses on new-build nuclear power systems and their supply chains, using a variety of VR techniques including “caves” and “power walls”.

A VR cave is a multi-wall system into which three or four people can physically enter, allowing them to walk through and manipulate a 3D model. With a power wall, one person controls the 3D environment while up to 20 other people follow the action on a rear-projected screen.

AMRC and Nuclear AMRC’s VR technology lead, Rab Scott, points out where gaming VR can fall short when faced with industrial applications: 3D games look realistic because of high rendering but they suffer from a low polygon count, and it’s this kind of detail that matters. “If I want to take a nuclear plant apart as if in a manufacturing CAD package, I wouldn’t be able to do it in an existing games-type package.”

As Scott puts it, a good-looking image isn’t what’s required so much as a precisely accurate interactive model that reveals whether or not you can fit a blowtorch in the right area and angle it to the right spot.

AMRC and Nuclear AMRC systems make use of the Oculus Rift HMD, but also Epson Moverio and Google Glass headsets, which technically speaking are Augmented Reality (AR) devices rather than fully immersive VR. It is only natural that there should be a crossover between the two concepts, given that the main impetus behind the current wave VR has been the convergence of technologies, including wearables and virtualisation, driven by the smartphone generation.

AR allows people to see the world around them with a virtual overlay, which can be as simple as a heads-up display (HUD) or as complex as 3D graphics and video. Epson’s Moverio headsets are fully binocular, employing Epson’s own high-temperature polysilicon panel technology to project stereo vision images into the wearer’s field of vision from both sides. This moves it out of conventional Google Glass-like HUD applications and well into the world of VR.

Full-scale virtual reality 3D design at University of Sheffield's Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centr

“We believe the AR market will grow considerably in the commercial market, such as arts and culture,” says Valerie Riffaud-Cangelosi, new markets development manager at Epson. “Museums were an early adopter. Also healthcare, retail and applications that have become really streamlined... like drones.”

Indeed, one of the most popular emerging uses of Moverio HMDs is for piloting drones, as it allows you to keep an eye on your done from the ground while at the same time seeing a bird’s eye view from the drone’s own mounted cameras.

Engineers on London's Crossrail are also making extensive use of AR with iPads – for example, holding a tablet up to a wall and allowing underground beacons to determine one’s location allows AR to reveal precise 3D models of what lies behind.

The advent of lightweight wearables combining AR and VR would therefore seem to be the next, logical step.

Riffaud-Cangelosi says: “We have some interesting partners working on the gesture interface. For example, you might open your hand, and suddenly a keyboard appears on top of it. You can then type on the keyboard with your other hand. All this is virtual. AR and VR can be very complementary.”

Helping the speed of VR adoption - so far, at least - has been the rejection – again, so far - of complex custom interactive handsets and bespoke gesture systems in favour of simpler games console controllers. Collette Johnson of Plextek observed that, having started off with a Razer Hydra handset, they soon switched to an X Box controller because the average trainee, typically aged between 16 and 28, required little or no training in how to use the latter. Sony effectively has this already in the bag for its £350 PlayStation VR launch coming this October.

Cost aside, if complexity alone stymied 3D TV, simplicity will boost VR: increasingly, HMDs can be adjusted to suit those who wear glasses without inflicting hours of discomfort, and short-sighted people can just remove their glasses altogether. Combined with simple operation and, eventually, wireless connections for the top-end systems, widespread VR adoption over the next two years seems all but inevitable.

Of course, if you insist that it’s just another passing tech fashion, you may enjoy Google’s alternative April Fool, the Google Cardboard Plastic. It’s not virtual reality, nor augmented reality. It’s just reality - as seen through plastic. ®