This article is more than 1 year old

Why Europe threw net neutrality slacktivists under a bus

Because 'good enough' is better than... years of fighting

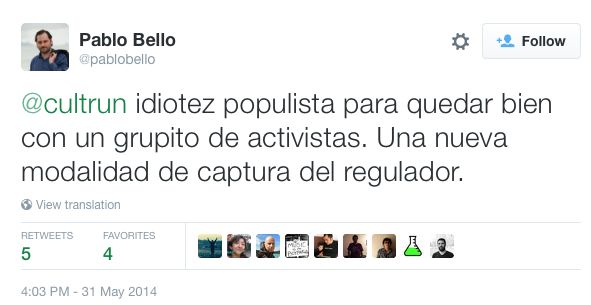

'Idiotez Populista'

Roslyn Layton and Silvia Elaluf Calderwood of the LSE decided to take a look at what happens when “hard” neutrality rules are implemented. They used real evidence. Several nations have passed hard neutrality rules, so the development of the telecomms market and the health of internet apps and services in each one could give us a useful guide. Did the customer ultimately benefit? What appeared in the evidence was striking. Net neutrality didn’t stimulate edge providers, which was its key raison d’etre, as Professor Tim Wu, who coined the phrase, had argued. “Levelling the playing field” with hard neutrality regulation didn’t encourage more services, or more diverse services. Specifically, zero rating didn’t tip the market towards a particular access provider anywhere.

Zero-rated HBO Go didn’t leap in popularity in Holland, and zero-rated TViN fell in popularity in Slovenia. Zero-rating tended to favour the incumbents. The Netherlands now has a "Netflix effect", as Netflix dominates the market. And guess who funded the "Save the Internet" lobbying this week? You've guessed it: Netflix.

“The Net Neutrality lobby will say that if you use Zero Rating you win market share. But we found the opposite. They never displace the No.1 incumbent.” Layton told us. Hard rules like outlawing Zero Rating cemented the established position of incumbents:

"My research shows that Netherlands has less edge provider innovation today than before the hard rules were put in place," Layton told us. "Things have gotten worse for edge providers in the Netherlands, only because the American internet companies have entrenched themselves even more in the country."

How could this be?

“Incumbents like Netflix have more first-run content. Zero rating was the only strategy the upstarts could use. It’s what you do if you can’t get any visibility at all.” Where activists take arms against Zero Rating, what they’re really trying to get data caps removed. Or in other words, they’re trying to get Netflix a free lunch.

Layton thinks that the Neutrality activists seized upon Zero Rating because their original fears had, over a decade, simply proved to be unfounded. There were other factors that gave Parliament confidence in dealing with the activists. Nothing seemed to satisfy the calls for ever-more, ever-harder legislation: no neutrality legislation was ever “pure” enough for the neutrality activists. Regulations led to confusion, and often perversely anti-consumer outcomes. And genuine public support for the regulations seemed to be thin to non-existent.

After passing neutrality regulation in 2010, operators in Chile could no longer market themselves on speed or quality - that was now illegal. (Seriously). They instead sought to put specific services outside the data bundle. But in 2014 the government banned that, becoming the first state to outlaw zero-rating. The murky ruling pleased no one. The regulator’s economic advisor memorably called it “populist idiocy from a small group of activists. A new form of regulatory capture.” Economist Pablo Bello on zero-rating:

What customers really cared about, as measured by the complaints to regulators, was performance, particularly on mobile networks; poor customer service, including lack of information and dodgy billing. Only 1.8 per cent cared about neutrality or zero rating. The only public complaint on file was by the local Net Neutrality activist group! The Netherlands banned HBO Go and forced an ended the free (but limited) Wi-Fi offered to travellers at Schipol airport, one of the world’s busiest hubs. Netflix now dominates the Dutch market. MEPs looked at the real-world examples and asked themselves, "Does anyone really want to live in the slacktivist’s world?"

“The business models that Net Neutrality lobby has been saying are so dangerous don’t exist today," says Layton. "If you are a telco and want to charge the next Skype a fee, then there’s a transaction cost to extracting that money. There’s no business model there.”

She thinks network operators had been slow to adjust to the public’s explosive demand for data. The report notes that, “What is frequently described as a predatory situation between operators and third party applications, might also be viewed as operators having the wrong business model in a time of change”.

"It turns out soft rules work better because you have the power of the carrot and stick," says Layton. "The stick holds operators' feet to the fire with the threat that the regulator can take more action. The carrot is the incentive for good behaviour and having a less regulated environment. When you have hard rules, you remove incentive for cooperation, so operators frequently put energy into litigation inside."

What Europe decided to this week was kill the issue politically. Europe is beset by problems - mass unemployment, and mass migration - but in this instance, it has dodged the bullet. By contrast, Layton sees huge problems ahead for the USA, where activists captured the regulator.

"The US rules are only supported by the President and three commissioners at the FCC. It has a shaky foundation, and is being challenged by nine lawsuits. On the other hand, the EU rules have the buy-in of the Parliament, the Commission, the Council—as well as many other parties, so they will likely last. And there’s not a tradition for litigation in the the way there is in the US.

“If this is the way you're going to do Net Neutrality, it’s fundamentally not a good way to do policy."

The US seems to have lobbied itself into a rancorous and expensive stalemate.

You can download and read the study ("Zero Rating: Do Hard Rules Protect or Harm Consumers and Competition? Evidence from Chile, Netherlands and Slovenia") here.

It's an eye opener.®