This article is more than 1 year old

The BBC's Space: A short history of 21st Century indoor relief

Digital: the magic middle-class makework word

State-owned, collectivised server farms

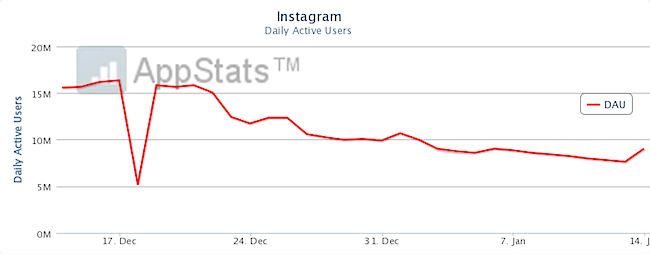

Ordinary people aren't stupid: they recognise when they’re being fleeced and react very strongly against it: whether its Instagram changing their T&Cs to assert more ownership or British bureaucrats trying to collectivise ownership of your property. Both are land grabs.

Instagram traffic backlash: People care more about their digital property than who owns the plantation

It’s the coercive transfer of property that they recognise and react more strongly against, not some ownership structure. And pointedly, readers didn't respond to state collectivisation positively, sighing with relief that the state had acquired ownership of their digital stuff. At all.

If you were to perform a “digital ethics audit”, the BBC doesn't emerge as one of the Good Guys, as Richard Hooper pointed out in his 2012 report for the government. The BBC routinely strips metadata from images that individuals send to the BBC, which Hooper pointed out is actually a criminal act. He also castigated it for not collaborating well with others on media formats.

So, trying to argue that the “public sphere was impoverished” using a definition of platform ownership is a bit like calling the Space Age "the Stone Age", because Neil Armstrong brought rocks back from the Moon. Of course you can try, but it isn’t really the full picture. It shows a tenuous, possibly utopian, grasp on reality.

The absence of “a public space” that, er, Space was supposed to fill did not actually mean “a space used by the public”, but “collectively owned”, in the Old Clause 4 of the Labour Party sense. But perhaps the ambiguity was intentional. Either way, it did the trick, and opened the BBC’s purse, and the idea was enthusiastically backed by the BBC Trust.

The Trust has a statutory role to see the BBC does its core job, but when it comes to anything digital, it tends to swoon like a giddy schoolgirl. The grander and vainer the digital proposal, the less critical was the BBC Trust. In 2011, the BBC Trust had described the doomed Digital Media Initiative as “something of which the BBC should be proud”. It was soon making the same swoony noises about Space.

What happened next?

The Space was announced as a formal collaboration with the Arts Council in 2012, which gave it a quasi-evangelical role in orienting other public sector organisations to doing web and apps, a "digital capacity-building" mission, as well as “connecting arts organisations with each other” (translation: networking, junkets). Here it took on a more Arts Council flavour, being a kind of digital portal for arts events****.

Not all audiences found their Space collaborations were a riotous success. “Given the size and reach of the BBC, we had hoped that the audience might have been larger and that a greater number would trickle through to our own website,” one participant noted. Interestingly, only 35 per cent of the arts orgs involved could identify a definite positive traffic impact on their sites from collaborating with the new quango. When audiences had the choice of going to the arts organisation's site or Space, they often shunned (PDF) the Space.

Naturally the theatres and museums were delighted with the helping hand. “89 per cent had ‘met’ or ‘strongly met’ their capacity-building objectives,” the Arts Council also noted (exec summary, pdf). “60 per cent reported changes in staff roles, giving greater prominence to digital.”

Yet merely conducting the evaluation of these modest pilots for the Space had created a mind-boggling amount of work. The Arts Council’s evaluation report drew on nine separate reports into traffic*****. The BBC had commissioned or funded five of these.

The Digital Trough

It’s too subtle for the Daily Mail to report, but there’s a story here, and it’s bigger than one about Syrian puppeteers and the paper’s ongoing obsession with Alan Yentob.

The British philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill once described the British Empire as "outdoor relief for the middle classes". The Victorians at the time were funding "indoor relief", a state-sponsored workhouse programme which invented jobs for the poor to prevent them being idle. Mill’s joke was that the Empire was a gigantic job creation scheme.

Today, “digital” has become the UK’s indoor relief program for the middle classes. Our digital do-gooders embark on a variety of Noble Causes, such as “teaching kids to code”, building “digital capacity” or hyping a "digital cluster", which are often responses to problems that don’t really exist. Sometimes – as we saw with the Government Digital Service (a quintessential digital-evangelical Mission) – the missionaries tout unique skills that don't really exist, but that can be used to bully and coerce.

The Space and the other now-abandoned "digital media commissioners" are a response to an imaginary scarcity, or an invented crisis, with the sketchy justification that the Cause was so Noble, no further justification was necessary. In the specific example of Space, the justification hinges on a definition of "public" that the public don't really care about. What they do care about is brushed aside.

What unites all these ventures – apart from the numinous word "digital" – is that administering them creates enormous amounts of work.

Our digital relief programmes today may even employ far more people than the British Empire employed in the Victorian era. From this estimate from the National Archives, the real number the Empire employed in the 19th Century is smaller than the 4,000 frequently cited. So while your kids doodle on a pointless arts app, or another "digital engagement" microsite goes dark, remember that at least the Victorians got some decent tea out of the deal. ®

Bootnotes

* It's actually an artistic homage to the Dazzle Ships applied to the former warship HMS President (1918), rather than a preserved Dazzle Ship.

** Or more charitably, you can only take so much of a good thing.

*** Here's Bill at The Register in 2002, busting net libertarian mythology with some gusto. From which we can infer that the flight from reality took place between 2002 and 2007, and may have coincided with a flight towards some work.

**** As of February this year, Ageh was still struggling to define the point of The Space. He devoted almost 5,000 words to a recent attempt before concluding it was "a higher calling".

***** Arts Council England, Artistic Assessments (January 2013); Arts Council England, Comprehensive Evaluation: Marketing and Communications for The Space pilot (2013); CogApp, The Space: User testing research (November 2012); eDigital Research, Pulse survey – website survey: Initial findings (August 2012) Independent evaluation of the pop-up Space user survey; Digital, The Space: Pilot analytics report (February 2013); Hassell Inclusion, User testing of The Space with disabled users (December 2012); MTM, Evaluation of The Space: Impact on Participants (February 2013); An independent evaluation of the impact of The Space programme on participating organisations; MTM, Evaluation of The Space: Artistic quality and innovation (December 2012); TrendSpot, The Space: Pulse evaluation deep dive (February 2013).