This article is more than 1 year old

Get thee behind me, Satanic mills! Robert Owen's Scottish legacy

Inside the works of Scotland's industrial revolutionary

Mind your ears

The mill operated that way until the 1950s, when the inefficiencies of running belts the length of the building became impossible to ignore. Generators were fitted to the main shaft, and wires carried power to electric motors running the machinery. Within five years it was clear that more power was needed, and mains electricity arrived to supplement the generated power until 1968 when the mill finally closed its doors.

New Lanark was all but abandoned for the next decade or so, falling into disrepair and gradually stripped of anything which could be recycled or sold off, until 1974 when a conservation trust was set up to preserve the site, as a model example of British industry, but also as a tribute to Owen who did so much to change it.

These days, New Lanark is a residential village; people live here, and most of the houses are occupied by locals who undertake restoration and maintenance in exchange for (quite literally) living in a museum. Visitors have to park at the top of the hill, which provides a suitably dramatic approach on the way in, but can prove a trial at the end of a day’s wanderings.

Around the village are spread various sites of interest – the school, the mill, the cooperative shop, and Owen's house which contrasts nicely to a typical workers’ house – he may have been a socialist, but he was no communist.

Three of the four mills are still standing; one is a hotel and another houses the souvenir shop amongst other things, but one mill has been converted into a visitors’ centre and it’s here that the sound and grime of the working conditions can be most-easily visualised.

Here we also find the “Annie McLeod Experience” – a walking-speed ride that carries you though life at the mill circa 1820. Annie has recently started working on the mill floor, and with some nice lighting effects, and a particularly-impressive hologram or two, she shows what her life is like, though to get a real feeling for the mill you’ll have to go up a floor to see a machine in action. You can get a taste for the authentic experience in the video, below.

There’s only one working machine, where there would have been four, but one is more than enough to show how noisy and unpleasant the works would have been at their peak. The space around the machine is filled with examples of the thread and fibres that would have been manufactured at the mill, and some film showing how cotton was picked, packed, shipped, and finally delivered on horseback from the other side of the world.

There are also some children’s games – Peever (aka hopscotch) boards are laid out, and children can have fun with hoops and skittles, not to mention the rather fine “Rise and fall of the unscrupulous master” that lets one climb the steps of career and achieve the pinnacle of success for only a moment before pitching down the perilous slide of disaster.

The symbolism might be lost on the smaller children, but the short slide can be enjoyed by all.

Scattered around the room are quotations from the good Owen, who certainly had plenty to say on the subject of unscrupulous masters, and the rights and responsibilities of the citizenry. He was only 28 when he bought the mill from the man who would (that same year) become his father in law, but he already believed that improving the life of the workforce was essential to improving society as a whole.

According to Owen: "I know that a society may be formed so as to exist without poverty, with health greatly improved, with little, if any misery, and with intelligence and happiness increased a hundredfold."

With that in mind his intention was to avoid employing children, and to provide day care from the moment they could walk (getting the mothers back into workforce as a happy side effect). At three years the children would start school, and they’d be there at least until the age of 10 with further education on offer.

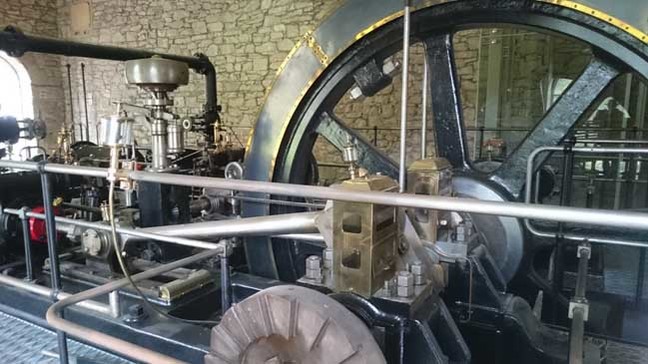

Borrowed from Philiphaugh Mill, Selkirk, and looking like a steam engine should

The education wouldn’t end when school was over. In stark contrast to received wisdom of the time Owen thought adults should be educated too, but that would require another new building.

Building the school and “The New Institution for the Formation of Character” was expensive, and the partners who’d helped buy the mill were not convinced such a thing was necessary, or desirable.

Owen wasn’t someone who’d give up easily, and on 31 December, 1813 he bought out his original partners, replacing them with more liberal-minded recruits who agreed to take only five per cent return, leaving the remaining profit for education, medical care, and other community benefits.