This article is more than 1 year old

The Register's resident space boffin: All you need to know about the Pluto mission

Meeting a cold dwarf hasn't put off NASA one bit

I love a planet with a little atmosphere

To almost everyone’s surprise, the first high resolution shot of Pluto revealed no impact craters at all, and a series of 3000m-tall mountains that can only be explained, for now at least, as being composed of water ice. Other images show extensive plains of ice showing polygonal patters that might be signs of convection in the surface layers.

Some leap to the conclusion that this young surface is a sign that Pluto is active now; that the surface of the planet is being renewed by a deep-freeze equivalent of volcanism. If that’s true, explaining where that heat comes from is going to be a puzzle.

Active geysers of nitrogen had been found on Neptune’s moon Triton in 1989, but the source of heat for that was thought to be tides. Significant tidal heat wasn’t expected at Pluto; our understanding of those processes might be wrong, or that the heat is coming from somewhere else, such as from the gradual cooling of underground seas of water.

Other, more complex processes might be at work however: Pluto has a thin atmosphere, much of which freezes onto the surface when far from the Sun during Pluto’s elongated orbit, and evaporates again when warmed. This movement of material between the surface and atmosphere might have big effects on Pluto’s appearance.

The dwarf planet’s atmosphere, probed by viewing the Sun in ultraviolet light as it passed behind Pluto, was found to extend to at least 1600km above the surface, and some of it joins the solar wind, forming a tail of ions downstream that New Horizons detected directly.

These moons aren't balloons, or named

Pluto might be losing 500 tons of atmosphere per day, far more than is lost at Mars.

Pluto’s large moon Charon is particularly puzzling, showing a young surface in places, deep canyons, and what appears to be a mountain that’s gradually sinking into the moon’s icy crust.

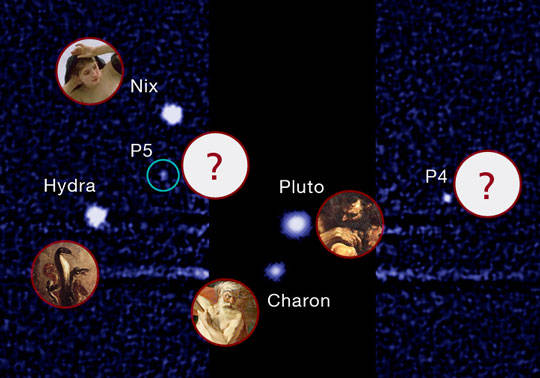

The north pole of the moon is dark, and might be where gases that have escaped from Pluto have frozen onto Charon’s surface. Images of the other four tiny moons have also been captured. As these are only a few tens of kilometres across compared with Pluto’s 2,370km diameter and Charon’s 1,200km, these are little more than pebbles, but could still provide valuable information on the Pluto system’s history.

The hard work of getting to Pluto is done, and the mission team is understandably elated. The probe is sending back its data, and plans are afoot to send New Horizons on to another target even further from the Sun.

The public had a taste of the excitement of a planetary encounter last week, but the mission’s scientists are relishing the years of hard but rewarding work ahead to understand the last data from our first survey of the Solar System. ®

Dr Geraint Jones is from UCL’s Mullard Space Science Lab, and has had stints at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and the Max Plank Institute for Solar System Research. He currently lectures on planetary science and researches areas as diverse as planetary atmospheres, cometary science and the solar wind, and appeared at El Reg’s last Christmas lecture.