This article is more than 1 year old

Charles Townes, inventor of the laser and friend to both science and religion, dies

Coherent light, coherent thinking

Obituary Charles Hard Townes, one of the winners of the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics for developing the laser and a pivotal player in astronomy and reconciling science and religion, has died at the age of 99 after a brief illness.

"Charlie Townes had an enormous impact on physics and society in general. Our department and all of UC Berkeley benefited from his wisdom and vision for nearly half a century," said Steven Boggs, professor and chair of the UC Berkeley Department of Physics.

"His overwhelming dedication to science and personal commitment to remaining active in research was inspirational to all of us. Berkeley physics has lost a true icon and our deepest sympathies go out to his wife, Frances, and the entire Townes family."

Townes was born on July 28, 1915, in Greenville, South Carolina and was a precocious youngster, eventually earning his BS in physics at the tender age of 19 before completing his PhD at Caltech in 1939 with a thesis on isotope separation and nuclear spins.

He joined the legendary Bell Labs shortly afterwards and spent the Second World War designing radar systems. Once the conflict was over became a professor at Columbia University and focused his research on using microwave technology developed at Bell for the emerging field of spectrography.

Seeing the light

In 1951 the 35-year-old Townes was sitting in a public park in Washington DC when he was struck by a remarkable idea which he later likened to a religious experience. Townes though he could see a way to creating a pure beam of short-wavelength, high-frequency light, what we now know as the laser.

Einstein had proposed that such a device would be possible, but the scientific community was skeptical. When Townes began work on the project his fellow scientists told him to stop wasting his time.

"Look, you should stop the work you are doing. It isn't going to work. You know it's not going to work, we know it's not going to work. You're wasting money, Just stop!" he was told by the chairmen of his department Isidor Isaac Rabi and Polykarp Kusch, fellow researcher Edward Teller recounts.

Townes argued his case and refused to give up on the research. He later explained that he was able to refuse to stop his research because he had tenure, so there was nothing they could really do to stop him.

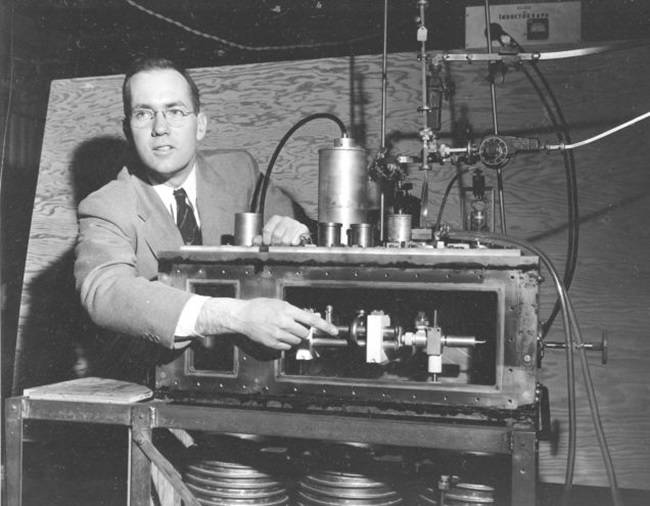

Three months later, in 1954, Townes and two students, James Gordon, and H. J. Zeiger, successfully built the first microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation (Maser) using ammonia gas. His boss immediately apologized to Townes.

Townes and the "impossible" Maser

Four years later Townes and his brother-in-law (and future Nobel Prize winner) Arthur Schawlow, conceived of a system that used mirrors at the end of a gas chamber to create a laser. In 1960 Theodore Maiman used these principles to develop the first laser, and Townes instantly saw the uses of the system for communications.

"Light has a very high bandwidth," he said. "You can put an enormous amount of information on one light beam. One light beam can carry all the information that is transmitted in the world, in principle. I realized that and knew it would be of some importance, but didn't know quite how important."

Bell Labs promptly patented the laser, while Townes retained his patent on the maser, although he made it open source in the name of scientific advancement. In 1964 Townes got the Nobel Prize for his discovery, along with Russian boffins Aleksandr Prokhorov and Nicolai Basov, who had independently developed masers.