This article is more than 1 year old

Britain’s forgotten first home computer pioneer: John Miller-Kirkpatrick

The electronics genius who nearly beat Clive Sinclair at his own game

Home life

Miller-Kirkpatrick undoubtedly knew that machines like the Nascom and 380Z were coming, along with the likes of the Apple II, Commodore Pet and Tandy TRS-80, which were launched in the US during 1977. He certainly didn’t rest on Scrumpi’s laurels, but times were hard in the Miller-Kirkpatrick household. His daughter Kirsten had been born deaf, and so John moved the family during the long hot summer of 1976 from Hemel Hempstead to the Buckinghamshire village of Chalfont St Peter in order to allow Kirsten to attend the best schools for hearing-impaired kids in the area. He named the house "Tintagel".

His own health was troubled. As a child, he had suffered from leukaemia but the treatment had been seemingly effective. Perhaps it’s that earlier brush with mortality which made John so active in later life. It’s hard not to conclude that he realised early on that life could be short and that we all owe to ourselves to make the most of what time we may have. Either way, around 1976 the disease returned.

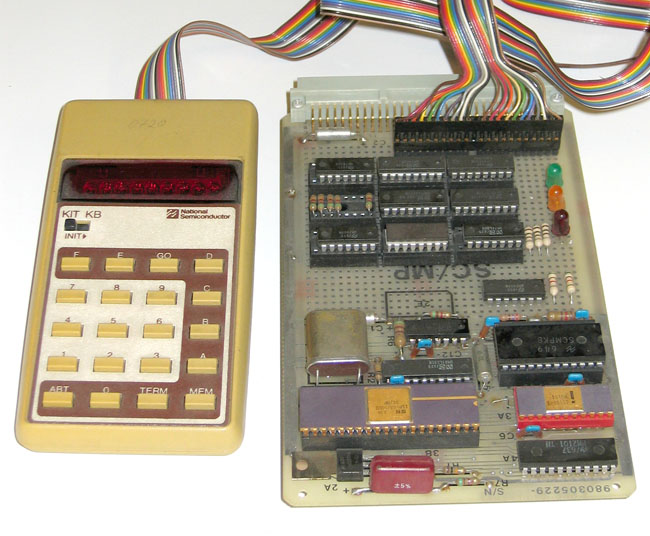

Yours for £140: National Semiconductor’s IntroKit and KB Kit

Source: Colin Phillips

Not that he was one to let this get the better of him, and he continued to show the same fighting, fun-loving spirit as he always had. His daughters both recall John’s keenness on belting around South Buckinghamshire in his Jaguar. “We used to get taken out to country pubs in his Jag,” remembers daughter Kirsten.

“We used to go out for drives which I have since discovered was probably to a) find little country pubs and b) find a new home,” adds her sister, Ashleigh. “Mum said they used to write a list of L, R and then just drive and turn according to the list - this was fairly adventurous and spontaneous, a trait of my dad’s I would suspect.” Sometimes he’d let the kids choose the next turning.

John often took the kids to London on his trips to the ETI offices and the family were at the head of the queue when Star Wars premiered at the Odeon Leicester Square on 27 December 1977.

Inspect a gadget

Play was important to John, but so was work. While his illness soon forced him to work from home - wife Jane would continue to manage the Bywood office in Hemel Hempstead every day - he never let up. Both Kirsten and Ashleigh separately recall encountering him still awake in the wee small hours, still hard at work on electronics projects.

“I used to hate storms when I was a child and woke up during the night one time,” says Kirsten. “However, I found my father in the dining room where he was tinkering away with his electronics work and he allowed me to stay up until the storm passed.”

“I often thought he was up early for breakfast only to discover that he had been up all night!” adds Ashleigh.

The girls grew up surrounded by their father’s magazines, journals, sci-fi books, rock records, that de rigeuer feature of every middle-class 1970s English living room, the tropical fish tank - but mostly his electronics handywork. “Solder kits, chips, circuit boards, wires and pliers, home made digital clocks, a static electric resin door stop and other detailed projects and inventions filled our home,” recalls Ashleigh. The dining room became his make-shift office.

“The carpets often held onto bits of wire, solder and the occasional chip which my dad convinced me were robotic woodlice. I would sit on his knee ‘helping‘ solder and choosing lengths of coloured wire.”

Late nights and family rites

Adds Kirsten: “There was one ‘woodlouse’ that had a wire connected to a remote control that he had made up. Looking back, I’d say it was a genius thing to have done as I don’t know of any such remote controlled ‘toys’ available for sale on the shelves of shops 40 years ago. This ‘woodlouse’ had legs that walked.”

Miller-Kirkpatrick continued to work on his computers too. During 1977, he revised Scrumpi, replacing its processor with the newly released SC/MP-II chip, a lower power, cheaper version of the original Scamp, this time based on NMOS technology. Bywood knocked the Scrumpi’s price down to £46 and released the Scrumpi 2, a physically larger board, at £56. Later in 1977, he tweaked the Scrumpi 2 to add slots for extra RAM and PROM. A more expensive, ‘F’ version of the Scrumpi 2 came with these slots filled, with an extra 512 bytes of RAM and 512 bytes of PROM.

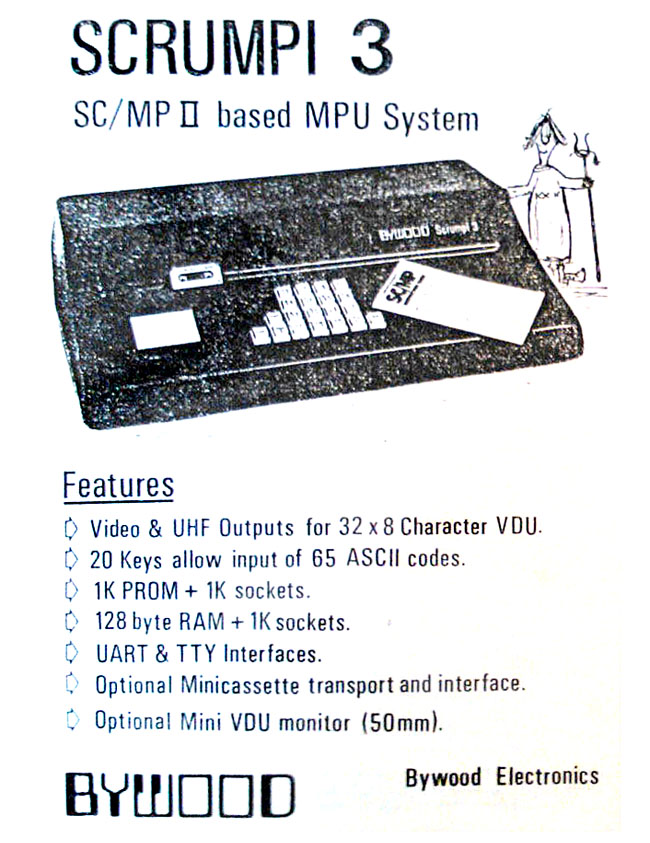

Aware of the major limitations of both the Scrumpi 1 and Scrumpi 2, Miller-Kirkpatrick was already working on a third version and this debuted in the Summer of 1978. No more switches and LEDs - the Scrumpi 3 had a VDU output and a 21-key keyboard: 16 character keys, four mode-selection keys and an "Interrupt" button.

Introducing the Scrumpi Mk III

The Scrumpi 3 was lauded by Electronics Today International as the “cheapest” board micro with a VDU output. “Bywood has managed to squeeze all 64 upper case Ascii characters onto a 21-key keyboard. This is achieved by the use of three shift keys. One soon gets used to using the shift keys and although it would be more convenient for entering hex code if the lower case characters were 0-9 and a-f, the current layout has presumably been chosen to ease a general purpose teletype.”

Unsurprisingly given Miller-Kirkpatrick’s talent for journalism, “the two handbooks are well and entertainingly written, starting from absolute basics and working up, so that someone who had never heard of a microprocessor before would soon be able to use the Scrumpi,” the review noted, though it also said “Bywood consider that ‘the PCB is its own circuit diagram’ and that further documentation is therefore unnecessary.”