This article is more than 1 year old

Delia and the Doctor: How to cook up a tune for a Time Lord

Making music from broadcast test equipment the Radiophonic Workshop way

The Art of Noise

In the context of music composition, Derbyshire’s notion of making something from nothing needs closer examination. One could argue that all composers make something out of nothing; crafting ideas into musical arrangements. However, with relatively few exceptions, most are writing with specific instruments in mind. Where Derbyshire and her colleagues excelled was in creating new instruments, often, seemingly, out of nothing.

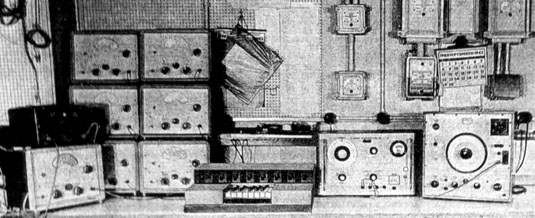

Seven Advance N1 signal generators and keying unit. A B&K wobulator is to the right

Indeed, most of the equipment appropriated by the Radiophonic Workshop consisted of signal generators and filters used for BBC engineering work. In short, it was test equipment intended for use to measure the response of circuits: put a sine wave into this piece of radio or TV kit here and see what comes out the other end.

For the broadcast engineers, rather than examine the results audibly, more often than not, the output would be viewed on an oscilloscope to check for signs of distortion, noise and phase artefacts. In many cases, the frequencies being analysed for broadcast purposes were way beyond human hearing.

Hissing with confidence

Furthermore, white noise would be used by the engineers to check the responsiveness of circuits. Again, it was unlikely this would be heard either, as untreated white noise is unpleasant to listen to. Just think of the sound of an old analogue TV without the aerial plugged in and you’re getting close.

Unlike a sine-wave generator, white noise doesn’t have a specific pitch. In fact, it is deliberately random and is designed to contain an equal amount of all the frequency components across the spectrum being examined. Again, for TV and radio use this frequency range would greatly exceed human hearing. So no point in listening to that then.

Well maybe, maybe not. Monitoring the response of audible white noise can be useful in acoustic environments, as it highlights resonant frequencies (a honking or booming emphasis) and damping (typically high frequency loss). A quick blast of white noise (and its colourful cousin pink noise) when monitored in a number of different positions within the room, hall or chamber, can identify the equalisation tweaks required to compensate for the environment’s acoustics.

While this describes how a natural environment can shape the response of white noise, the BBC engineers would also have electronic filters that they could apply to limit or tailor the frequency range being examined, as they went about their business testing and calibrating broadcast and recording equipment.

Filter tips

These filters wouldn’t just have to work on white noise either, any content could be fed through them. Three types of filter are commonly used: low pass, band pass and high pass. So with a high-pass filter, the high frequencies would pass through unfettered and the bass would be attenuated. Just think of a dance music track where the mix transforms to sound like it’s tinny headphone spill and you’ve got an extreme example.

Conversely, with the low-pass filter, the bottom end would be more pronounced as the high frequencies had been rolled off. Again, dance music uses this to good effect when the mix is filtered to sound like it’s just a burble of bass in a club toilet. On individual sounds and instruments, more subtle adjustments to minimise bass with a high-pass filter can be used to make the recording more pronounced in the mix and less muddy. Likewise, the low-pass filter can tame bright recordings so they sound warmer and less brittle.

The band-pass filter is fun too, as it can roll off both high and low frequencies so that you can narrow down to a particular range within the frequency spectrum. A typical example would be recreating the sound of a voice over telephone where both the bass and treble are attenuated leaving a squawky mid-range content. It’s also possible to shift that narrow notch of frequency bandwidth up and down the spectrum, so that interesting sweep effects can be heard. Indeed, this treatment forms the basis of the wah-wah pedal – think Hendrix's Voodoo Child intro [YouTube clip] or repetitive chiming of Massive Attack’s Protection [YouTube clip].

Room 12, Workshop 2: EMI tape recorders in the foreground with various signal generators at the back

All those examples highlight how the bare bones of simple test equipment can be applied creatively. While a sine wave gives the purest tone, also on hand with the flick of a switch among the various signal generators were harmonically rich square and sawtooth waveforms along with separate white noise apparatus. With these scant resources, the Radiophonic Workshop could begin to make some interesting noises.

More interesting still was the fact that so much of the sound creation was entirely electronic in origin. The cues for “clouds” and “wind bubbles” that Grainer mentioned in his composition notes to coincide with the title visual effects were up to the Radiophonic Workshop to interpret. And so they came about by filtering white noise. Derbyshire didn’t just set up a filter to hiss a bit and leave it there, producing the effect involved a performance element with some carefully timed knob twiddling.

Speech therapy

Gutted piano used for Tardis sound effect

Undoubtedly, the Doctor Who theme features some innovative sounds, but the programme itself needed regular sonic sweeteners too: the voice of the Daleks, for instance. This treatment was created by Brian Hodgson using a ring modulator, a circuit that multiplies two incoming signals.

To get the effect, the actor’s voice was modulated by a 30Hz sine wave that, together with the diodes that formed part of the circuitry, produced the menacing warble and distortion of the Daleks. A similar treatment was used for the Cybermen. You can hear how it works, experiment with the controls and find coding info on how to put your own emulator together on the BBC’s prototype page here.

Another example of Brian Hodgson’s brilliance was the sound of the Tardis take-of, created by scraping his front door key along the wound strings of an old piano. Edit, loop, vary speed, and add echo to taste.