This article is more than 1 year old

Classic telly FX tech: How the Tardis flew before the CGI era

How the special effects boys made magic in the 1960s, 70s and 80s

Best of PALs

In the early days, spacecraft were shot at standard camera speed. Only later would filmed effects be captured at high speed to ensure that, when slowed down to the correct speed, their jerky movements would be smoothed out thereby creating a better sense of scale. Ian Scoones’ work on the Jaggaroth spacecraft in City of Death, shot in 1978, is still gorgeous to look at more than 30 years on.

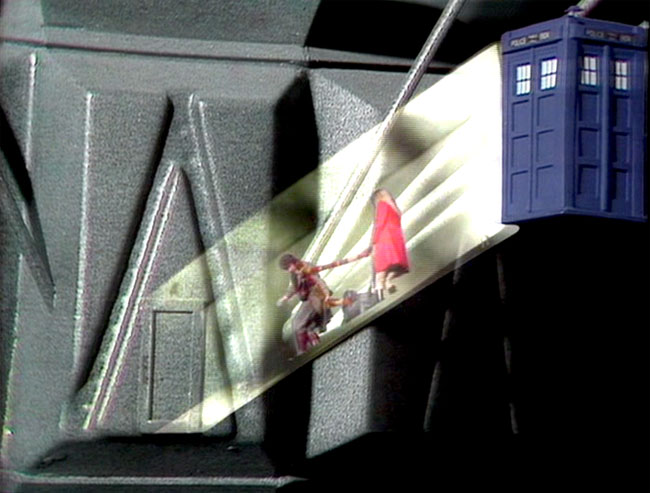

You could do some clever stuff with CSO, if you were careful

Source: BBC

Effects shots which required actors to appear in the shot would be achieved by masking off a section of the set in black, then filming the thesps doing their thing. The film or videotape would be rolled back through the camera, and re-exposed, this time to a real or a model set masked to ensure the already exposed areas of the film were not exposed a second time. The result: one piece of film containing two separately shot images which combine into a single shot. This is how the lifts in the Dalek city on Skaro were shot in the second Doctor Who story, The Mutants, later renamed The Daleks, were achieved.

This trick, like almost all of the early approaches to effects work, derived from cinema technique, despite the use of videotape and electronic cameras. It wasn’t until the adoption of the PAL (Phase Alternation Line) TV system – developed in 1962, established as a European standard in 1963, and put in use by the BBC in 1967 on BBC 2; BBC 1 followed in 1969 – that colour became possible and engineers could begin playing with the signals to see what could be achieved entirely in the video domain.

PAL extended the number of lines to 625 - only 576 are used for the visible picture - again transmitted to form 50 alternate-line fields every second. Each field was interlaced with its predecessor to display 25 frames each second. Like System A, PAL primarily transmits a monochrome image - the main signal defines the brightness of a given point on the screen, called its ‘luminance’. Within that main signal, there is a quadrature amplitude modulated sub-carrier sending the colour information - a signal that black and white TVs would simply ignore and which was configured not to interfere with the luminance signal.

CSO behaving badly

Source: BBC

PAL’s colour signal transmitted red and blue colour levels - ‘chrominance’ - with the green level derived by taking the combined red and blue signal strength at a given point away from the luminance level at that same point. That saved bandwidth. So did transmitting colour data for effectively half the number of lines, though that was the result of PALs alternation of the colour signal’s phase to help correct phase errors by cancelling them out. Fortunately, the human eye’s colour resolution is less effective than its ability to detect changes of brightness, so the lower colour resolution was not a problem.

One upshot of all this became known by BBC engineers as Colour Separation Overlay, or CSO. Engineers working for the broadcasters on the independent network called it Chromakey. Whatever the moniker, the essence of the technique involves substituting one picture signal for part of another, the substitution keyed to a specific colour, hence the ITV name.

The signal from the foreground camera was run through a ‘key generator’ which essentially created a video mask derived from the key colour. After the key signal had been adjusted for hardness or softness, it was used to control the video mixer being used to combine the output from the foreground camera and the signal from the background camera.

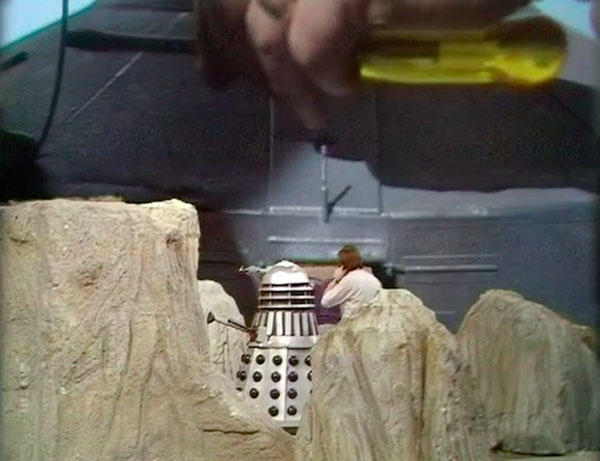

Foreground, rocks and Daleks. Background: Dalek saucer and... er... technician’s screwdriver

Source: BBC

Unlike CGI, the CSO mixing was done live, before the shot being recorded, so any errors remained for all to see. Studio-recorded TV in the 1970s and 80s generally lacked the time to remount shots with iffy CSO, so directors just had to live with glitches, of which there are many to be spotted in Doctor Who episodes from the period.

We’ve all seen them: dark or coloured lines at the borders between keyed picture components; areas of the foreground picture appearing to disappear, the result of studio lighting casting light of the same hue as the key colour and incorrectly triggering superimposition, or the key colour backdrop itself reflecting off a shiny object; and of course hair or glass not looking right because the intensity of the key colour had dropped out of range while passing through it.

The key colour - usually yellow in early 1970s Doctor Who episodes, and blue later on - had to be carefully selected to avoid replicating natural human skin tones. With the colour set, parts of the set into which separately shot images would be later dropped - radar screens, windows, stuff like that - would be painted in the key colour. If the lighting was a bit off, the apparent colour intensity would fall below that the mixer was expecting to key an image to. Costumes had to be designed to ensure they didn’t include the key colour. Naturally, that didn’t always happen.

Chromakey monkey asleep at the wheel? The yellow section should have shown a futuristic monitor display

Source: BBC

And sometimes Vision Mixers, the guys charged with making the effect happen, simply forgot to key in the image to be superimposed. Watch out for unexpected large areas of yellow or blue behind the Doctor or others. Examples are legion, particularly when yellow was used as the key colour - blue might just occasionally be mistaken for sky.

With time for patient, careful set-up, CSO could be quite effective, and there’s plenty of good CSO in classic Doctor Who too. The best examples are barely noticeable. But time was not a plentiful commodity during the recording of a Doctor Who episode and the results could be very poor indeed.