This article is more than 1 year old

Are you for reel? How the Compact Cassette struck a chord for millions

From fuss-free audio tape recording to Walkmans, it's all in your head

Highly sprung

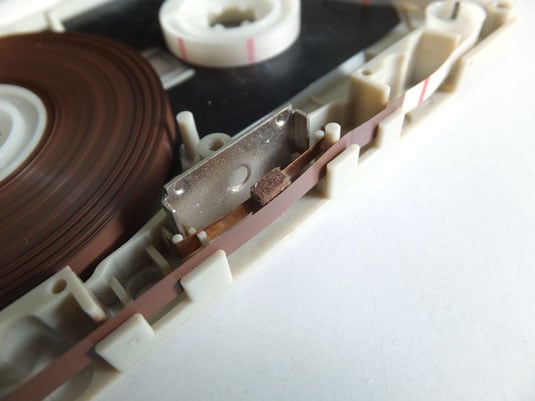

Inside a Compact Cassette, there's a pressure pad that is an important component. It's mounted to a short piece of sprung metal that produces a contact force between 0.1N and 0.2N to keep the head comfortably against the tape.

Sprung pressure pad and the silver metal plate behind it, which provides shielding from stray magnetic fields

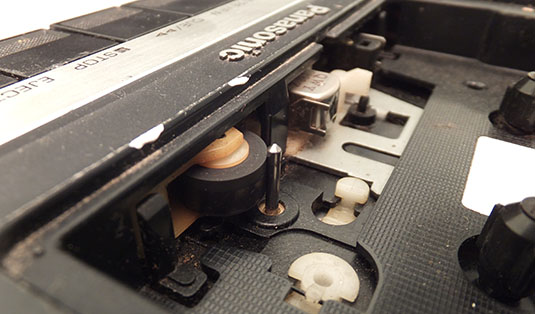

As on recorders before it, a capstan and pinch roller performed a similar sandwich act of pulling the tape through at a constant rate, like clothes through a mangle. That said, the 2mm diameter capstan Philips chose was precision made, and certainly not intended to mangle the tape, but if the capstan was bent or had an uneven surface, it could cause major problems not only to the tape but also wreck the feed speed.

The capstan – the thin, silvery, spindle in the cassette recorder – is the main component in governing the tape speed. It was much smaller than capstans on other recorders, which was needed to reduce its flywheel size, again, to keep the recorder portable. Using gearing, the same motor running the capstan would perform transport winds and determined tape take-up using a slipping clutch to decrease its speed as the empty spool filled up with tape.

Capstan and pinch roller on Panasonic RQ-2734 from 1976 and still working

All these aspects engaged when the tape was in play or record with the head array and pinch roller moving into place, rather than being fixed like on the RCA cartridge. For fast winds, the head assembly retracted, so there were no concerns of wear and tear caused by the head. The retracting array meant removal of the cassette posed no problems and also enabled the tape to be recessed slightly, and covered from both sides; protecting it when handled.

A bit of a flutter

With the motor driven by a current alternating at 32Hz, the capstan at 7.5Hz, the slipping clutch at 4.6Hz and the flywheel belt at 3Hz, this combination of components produced ‘flutter’ – minor, rapid speed variations in other words. It was something Philips couldn’t realistically eliminate on a consumer-focussed product. Instead, it had to set tolerances, weighting the acceptable limits against the audio world's DIN 45507 specification on frequency fluctuation.

Lest we forget that Philips wanted all of this to work its debut model, the EL 3300, from five 1.5V C cell batteries and to continue to function as the voltage supply declined from 7.5V to 5V or even less. The widespread use of transistors – a marvel of the age – made all this possible, with the EL 3300 also having to knock out 0.25W from its 2.4in loudspeaker or record from the supplied EL3797/00 moving-coil microphone and detachable EL3796/00 remote-control cable.

The first Compact Cassette recorder: Philips EL 3300. Source: Philips Company Archives

The front panel was sparse and the controls were a joystick of sorts, rather than the keys that would later dominate cassette machines. You’d need to hold down the separate red button before sliding the transport into the play position to engage recording. A quaint moving-coil meter to the right indicated the recording level and dials on the side controlled record and playback volumes. The two DIN sockets were for the mic and remote control functions.

The EL3300 measured up at 113 x 56 x 196 mm and weighed 1.5kg, which is certainly portable. It cost 300DM at launch, and it didn’t quite live up to the cassette spec potential: the audio frequency response topped out at about 6kHz; the later EL3302 would improve on this with claims of 10kHz.

In the US, the Philips recorders were marketed under the Norelco brand and in November 1964 were sold as the Carry Corder 150. As a result of Philips’ decision to license the format for free, the Compact Cassette’s popularity was assured. Being suitable for use in cars was another bonus, even though the 8-track ‘Stereo 8’ cartridge did make considerable in-roads here, as the cassette tape still needed refinements to become more listener-friendly for music.

Harman Kardon cassette deck with Dolby B from July 1970

Indeed, prerecorded Musicassettes didn’t appear until late 1965 in Europe and the following year in the US. The introduction of Dolby B noise reduction on hi-fi cassette recorders – the Advent Model 200 being the first in 1970 – started a proliferation of what was in effect an analogue codec on mass-produced Musicassettes.

While replaying without Dolby B would be acceptable, it did mean that the listener was hearing a bright and slightly compressed sound and not experiencing the original dynamic range or equalisation of the recording. An explanation of Dolby's ingenious analogue signal processing is featured here.

Making tracks

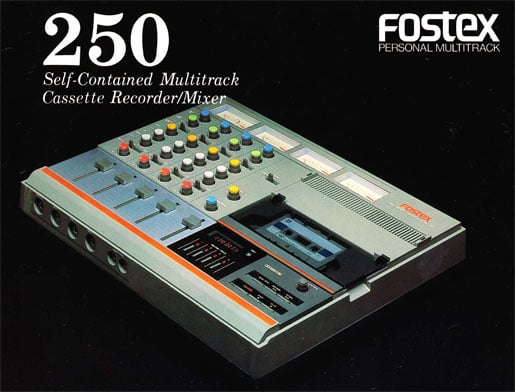

Fostex 250 4-track tape head

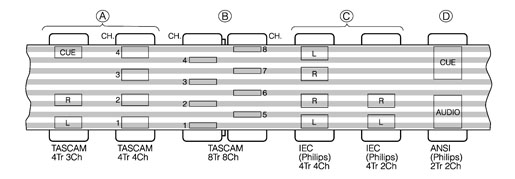

Despite being a Tascam trademark, the Portastudio - popular for taping demos and similar performances on a budget - stuck as shorthand for a multitrack cassette recorder. The early models allowed four-track recording, and the tape didn't have to be flipped over: you could use the whole of it in one go without having to pause, and at double speed, too.

Tascam and Philips tape track allocations

The speed allowed for better quality, but you’d only get 15 minutes out of a C-60 that would also need to be a CrO2 tape (made using chromium dioxide, which boosted the sound quality). Tracks could be independently recorded and played back, so you could build up a multi-instrumental and vocal recording.

Fostex 250 multitrack cassette recorder

Also these portable multi-trackers had an integrated mixer, so the 10-track bounce would be possible too, all from within one machine. Here’s how you’d do it:

- Record on tracks 1, 2 and 3, and while mixing these down to record on track 4 add a live performance. So that’s effectively four separate tracks into one mono track.

- Record more stuff, then bounce tracks 1, 2 and a live input onto track 3 (three separate tracks into one mono track).

- Record more stuff then bounce track 1 and a live track to track 2 (two separate tracks into one mono track).

- Now you’ve one remaining track to record on. The track count across four physical track totals: 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 10.

Tascam 238 8-track cassette recorder

Just about all four-track tape decks would have noise reduction on-board. I used a Fostex 250 which had Dolby C but Tascam and Yamaha models featured an alternative by dBx. Amazingly, Tascam even went so far as to produce an eight-track model that used the Compact Cassette.

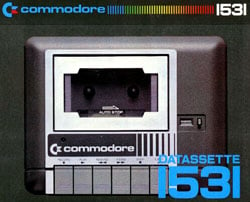

Commodore Datasette kept alongside many a Pet

There were other applications for musicians too, as tape backup of synth sounds, sequences and drum machine patterns could be saved on tape. There's more on this right here.

And it wasn’t just musicians who were doing this. The cassette tape was the backup medium for many microcomputer owners in the 1970s and early 1980s. It could handle data rates of 2kbs, notching up about 660KB per side on a C-90, close to a 3.5in HD floppy disk.