This article is more than 1 year old

My bleak tech reality: You can't trust anyone or anything, anymore

Two-factor authentication? Fine, if you trust the Feds

There are solutions

The ultimate solution to this problem would be a virtual appliance that I could install on my network which would stream updates and security configuration changes from a centralised cloud service. Here I could tap the expertise of a group like LastPass while still ensuring that the information I care about is subject only to the laws of my nation.

The truly paranoid would worry about backdoors being built into the app. The solution to that is independent audits. A requirement for those audits is that the auditors come from different jurisdictions, making it impossible to claim that all the auditors could have been ordered – or coerced - by any one entity to overlook such critical flaws.

Updates should be delivered via a pull (rather than push) mechanism, the updates posted to the site and the server software going out to grab them. There should be no means by which the centralised service could directly interact with the deployed base of servers. These updates could be similarly scrutinised to ensure that they do not introduce any back doors into the system.

I could go on, but I believe the point is made. We are heading into a world of cloud computing where trust is going to be a huge issue. It is no longer simply a matter of trusting that the software you buy works as advertised.

We now have to worry about ongoing and increasingly complex security threats, not only from criminals, but from governments whose laws and approaches to privacy and civil liberties diverge greatly from our own.

Trust as a design principle

The technosphere doesn't think like this. Very few design their products around trust, or the lack thereof. We've become obsessed with how the technology works and what that technology can enable; technology is easy, people are hard. How the technology we create integrates into the larger reality of politics, law, emotion and the other people-centric elements, is often overlooked.

In some cases it is simply a matter of having a limited target audience; American firms designing for American users, for example. It is impossible for most to really understand the intricacies of trust issues in all their variegated permutations. It is human to be limited in our vision, and scope of understanding.

The 2000s saw "secure by design" become a catchphrase as the exponential spread of always-on internet connectivity made remote attacks from random hostiles a part of everyday life. This decade seems to have latched on to "integrated by design" - a marriage of hardware, software, networking and cloud services under banners ranging from DevOps to Software Defined Networking/Storage/etc.

"Trustworthy by design" has been completely ignored, quietly brushed under the rug as inconvenient and bad for business. It is the elephant in the room that we collectively feel powerless to address. Companies don't want to waste resources worrying about it. Governments are all too often part of the problem, not the solution.

End users buy into marketing campaigns designed to make us feel as though we are somehow suspicious and guilty for worrying about such things. The scorn that technology companies – and technology magazines, reporters and bloggers – heap upon the concepts of privacy have made desiring control of your own data something that will get you ostracised.

We have created a culture of thoughtcrime - those desiring privacy are guilty of something, obviously, otherwise why would they want said privacy?

Demand change

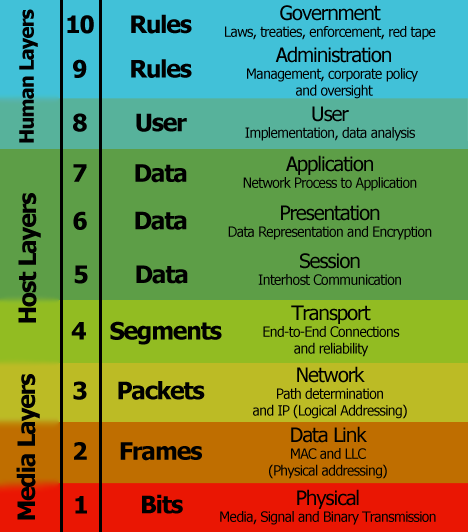

We need a new movement in computing, one that looks at all seven layers of the OSI model plus an extra three that take into account the human element, then works to design around every one of them.

As technologists, we must stop looking at user data as one more thing to monopolise and monetise; we need to treat data as sacrosanct.

We, as users, must not allow our data to be used to lock us into “solutions”, or be mined by corporations or governments. It's easy to understand the importance of securing data when we talk about passwords, but other forms of data are equally important. A journalist's contact list being mined could endanger their sources. As much as we hate to acknowledge it, revealing an illness or even an ethnicity that someone has kept carefully hidden could end up costing them their livelihood – or in some locales, even their lives.

Our data is no longer entirely under our control. As users we must examine every link in the chain of custody and ask ourselves "who could potentially gain access to our data and how?" We must demand steps be taken to ensure that nobody but us should ever have access to our data for any reason unless we explicitly allow it.

We need to demand this of the companies that create our applications. We must demand this of our governments and even the companies we work for. The alternative is a world without secrets; a world where one mistake – no matter how minor – can haunt us for a lifetime.

Humans are not particularly forgiving. We are cliquish and tribal, we seek constantly not to include others but instead to find reasons to exclude them. Our history is littered with discrimination based on every conceivable factor of our existence. This has manifested in everything from light heckling to segregation, slavery, torture and genocide.

It is easy to look at the more awful and extreme end of that spectrum and say that this is something that happened only in humanity's barbaric past, or in far-off places. We can abstract away the horrors of Darfur and Burma by telling ourselves that the people involved are somehow less than us - different, less civilised. How many are aware of the irony of the selfsame thought, one that creates an "us" and a "them" based on what would be nothing more than data in a spreadsheet: Country of Origin?

What happens when a racist gets hold of a great big blob of data? Could they misuse laws like "stand your ground" to find and harm people appearing in certain spreadsheet fields they don't like? Have we even begun to figure out how the misuse of this data could alter housing, insurance and related pricing? What would the mob do with that information when it feels entitled and on a mission? After all, Reddit sure got the Boston bombers' identities wrong.

We are not ready for Google Island. The human race has not evolved that far. We cannot even grant our governments powers to invade privacy without their immediate and blatant misuse. Powers created strictly to protect national security and deal with the very real threat of terrorism are used to spy on people putting out too many bags of garbage for collection.

Giant government databases of information that is supposedly properly curated aren't even right all the time - tapping US senators as terrorists among other failures. Are we really ready to have these same people dealing with mountains of unstructured data they've harvested from the tattered remains of our ever-increasingly-easily decrypted privacy?

Very few among us - maybe none - are worthy of the level of trust required to have complete access to our activities, beliefs, actions, associations and desires. Acknowledgement of this means designing the systems that store all of that information in a way that treats everyone as untrusted by default.

Are we – as creators and implementers of technology, as well as users and consumers of said technology – willing to ensure that data custody becomes as fundamental to design as security, connectivity and ease of use? If not, are we prepared for the future that our apathy will create? ®