This article is more than 1 year old

The Lynx effect: The story of Camputers' mighty micro

The cat from Cambridge that clawed its way to the top... almost

Business in trouble

There was a lot riding on the 128KB model. Christmas 1983 had not yielded the sales volumes Camputers and many of its rival manufacturers were anticipating. “We shipped a lot of units into retail through mid-1983, but at Christmas they just weren’t selling,” says Sore. “I don’t know what was selling, but it wasn’t computers.”

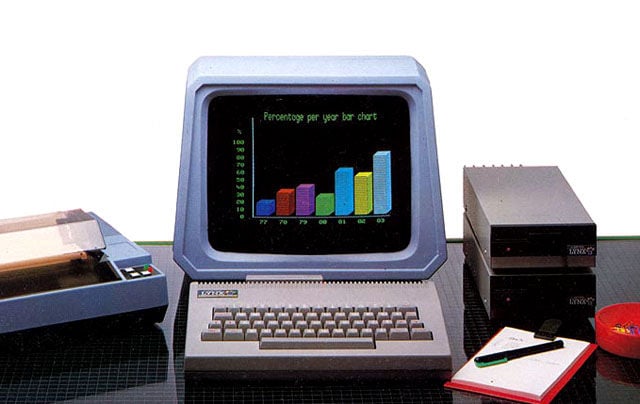

The 128KB was pitched at businesses and professional users, though you have to wonder now how many of these potential buyers would pop into Laskys or Dixons for their office equipment. Certainly, retail remained the focus of Camputers’ sales efforts, but the troubled Christmas and scary prospects of a very weak home computer market through 1984 prompted the company to emphasise the 128KB and its role in business.

In 1984, Camputers' future was riding on the 128KB Lynx and its hoped-for business audience

Enter, then, a rebranding exercise: the 48KB Lynx became the Leisure, the 96KB model the Laureate, though the name would be later appended to the 128KB Lynx too. The 48KB model was dropped by Camputers’ retail partners, who would to focus solely on the 96KB and - eventually - the 128KB models; the Leisure became a device only available through mail order. Its price was cut to £160. The Laureate was bundled with a pair of disk drives, a parallel interface and a copy of Perfect Software’s suite of productivity apps, all for just under £700.

But many observers questioned Camputers’ health. Dick Greenwood was encouraged to step down as Chairman, to be replaced by Stanley Charles of the company’s stockbroker, Statham Duff Stoop, which had organised the share issue the previous year. Charles pitched the rebranding as an attempt to change Camputers’ image, but he confirmed that the company was seeking further funding - a sign it was not selling enough computers.

“We have now reached agreement with a financial consortium,” Charles announced in March 1984, “and we are just waiting for the stock exchange paperwork to go through before we make a formal announcement about it.”

No one to the rescue

But their potential angel got cold wings and pulled out. Come May, Charles was forced to admit: “While one party has expressed an intent to ensure that the Lynx series will continue, no firm offer has been made.” The writing was on the wall. 24 members of staff were laid off - among them John Shirreff, he told me - and a creditors meeting called for early June. Charles’ hope that a would-be buyer would snap up the company before that meeting were dashed, and there was little choice left but to go into voluntary liquidation.

Camputers’ debts totalled £1.8 million, with £877,000 of that owed to its parent company, Plc. The firm’s total assets were estimated at £94,250.

Through the summer joint liquidators Hacker Young & Partners and Cork Gully negotiated two possible takeover deals, one with paper and stationery company Spicers, but neither came to anything. “There is still some interest being shown but there is not very much time left. Within a month someone will have to be found to continue with the project or it will have to be broken up and the parts sold off,” a spokesman for Hacker Young told Personal Computer News in October.

Two months later, Camputers finally closed down and its assets were sold to Anston Technology, a Cambridge firm founded specifically to buy Camputers’ assets, for which it paid £24,000, it was claimed at the time. One of Anston’s directors also ran Braefield Chapman, one of Camputers’ assembly sub-contractors and which would have undoubtedly been one of the firms owed money by Camputers. It had Lynx stock and pre-assembly components on hand. Dick Greenwood was asked to advise Anston on where it might take the Lynx range. “My purpose is to ensure that the Lynx continues,” he told PCN. “I’m currently tying up loose ends from a technical and production point of view.” He would soon become, with Chapman, joint head of Anston.

In February 1985, Anston announced that it would begin selling the 128KB Lynx, promising to cut the price from £399 to £299 and offer a 1MB disk drive for £269. The 48KB and 96KB models were culled. But there’s no sign the revived machine ever came back to the market, certainly not with any significant presence. By now Oric had also collapsed; Acorn, having teetered on the brink, had been saved by Olivetti; and Sinclair, a year after the launch of the business-oriented QL, was having a tough time - it would later be forced to consider taking money from publishing tycoon Robert Maxwell. Only Amstrad appeared to be flourishing.

Thirty years on

Looking back, Geoff Sore says: “We had to differentiate ourselves from the Spectrum because of the price differential. We were trying to appeal to a better class of customer, a more technical customer, but it was a much more capable machine, but it wasn’t as good at fancy, flashy games. And indeed the Commodore 64 eclipsed the Spectrum and everything else because of its games capability. We failed to fully appreciate the power of the games market, and we never really got to grips with getting enough output on the games side. That’s one reason why we didn’t sell enough machines.”

It is estimated that around 30,000 Lynxes were sold in total, only a third of them in the UK - the rest were bought in Europe. That’s rather less than the 40,000 units Camputers told journalists as the start of 1983 that it expected to produce that year alone.

Geoff Sore left Camputers in August 1983. After stints at Control Universal, a maker of Eurocard-format BBC industrial controllers, and at Pye, he founded a business manufacturing custom keyboards for industrial applications and, in 1988, founded precision motor company SmartDrive. He retired on health grounds in the early 2000s.

Dick Greenwood is still in the electronics business. He runs Circuit Solutions (Cambridge), a privately held contract manufacturer.

By the time, Sore left, John Shirreff, was long gone. He left when the administrators came in, a casualty, he hinted, of the job cutting programme. He went on to work for a variety of electronics and programming projects, some as a freelance, others as an employee. Some, such as stint with 80s guitar maker Staccato, combined his love of music and technology. He also returned to the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, Oxfordshire - he’d worked there before, in the early 1970s - to work on 3D graphical visualisations of scientific data. Today, semi-retired, he’s looking forward to getting hold of a Raspberry Pi. ®

The author would like to thank the many retro-tech fans for archiving home computing adverts, photos and documentation from the 1980s, without whom this feature would not be possible. Very special thanks go to Geoff Sore and John Shirreff.