This article is more than 1 year old

Drilling into 3D printing: Gimmick, revolution or spooks' nightmare?

Top prof sorts the hype from the science for El Reg

How the zeal about 3D printing emerged and why that's significant

Given the financial shenanigans since the credit crunch of 2008, a revival of American interest in manufacturing, as a kind of ethical alternative to financial services, should be no surprise. Also, efforts to "reshore" manufacturing from Asia back to the US are one area of common ground in American politics.

The average cost of a 3D printer as a product, both for use in industry and for use at a more residential scale, has declined enough in recent years for optimism about its potential to appear more than a little justified. Hobbyist or entry-level printers now retail for as little as $1000; professional ones for as little as $10,000. There has been no democratisation of 3D printing, that’s for sure; but, like the PC of old, it has got cheaper, and therefore more accessible.

A desire to rebalance the economy, make it more resilient in the face of international pressures and take advantage of cheapened, sophisticated machinery: these three factors have ensured that those who evangelise for 3D printing today are a little bit more than just a new generation of dot.com youth (late-1990s) or social-media youth (mid-2000s) with a peculiar fascination for real-world manufacturing.

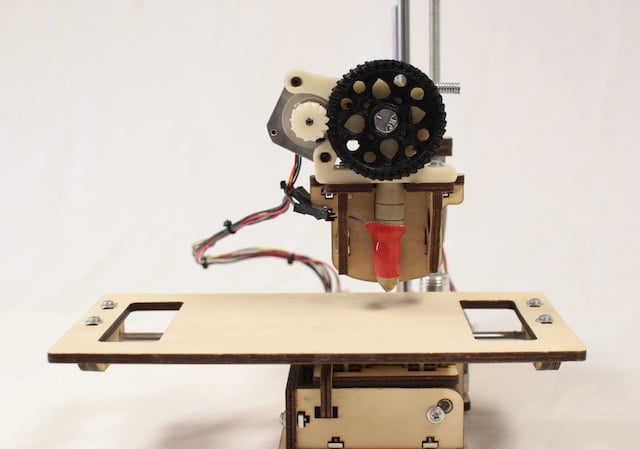

The Printrbot Jr: the ultimate budget 3D output machine at $449 (£280)

At the bottom, 3D printing buffs seek economic revival in small firms, firms which, in Anderson’s view, are job-creating (unlike conventional manufacturing), both small and global, both artisanal and innovative, and both high-tech and low-cost. Those who are over-passionate about 3D printing are really just making a misguided, right-on, petit-bourgeois attempt to reform capitalism by sector – toward the tangible and moral certainties of manufacturing, rather than the caprice of the banks. On the world economy, as well, mania for 3D printing displays a strong bent toward protectionism, import substitution and national economic independence.

That’s why, in his State of the Union address on 13 February 2013, President Barack Obama announced not only that 3D printing had "the potential to revolutionise the way we make almost everything", but also that he wanted to add another 14 "manufacturing hubs" to the $30m National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute that he set up in Youngstown, Ohio, last year. His purpose? To "guarantee that the next revolution in manufacturing is Made in America".

In the case of American boosters of 3D printing, an autarchic vision of the American economy coincides with an autarchic vision of the American home. This should not blind us to the considerable achievements already made by 3D printers when they have been used by multinational corporations; but it certainly should give pause to anyone hoping that household-based 3D printing by adults is going to take the world by storm. Nevertheless, the appeal of 3D goes beyond a few American homes and garages, and beyond the multinational firm. Politically, the appeal is greatest among the world’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) – always, for capitalism, the dominant source of employment, and always hailed as a major source of innovation.

It is not just Anderson and Obama in America who favour 3D printing. In the UK, the Lib-Con government has belatedly begun to talk it up, too. David Willetts, minister for universities and science at the UK Department for Business Innovation and Skills, has linked advanced materials, one of his own preferred "eight great technologies", to 3D printing, and in October 2012 went so far as to announce all of £7m ($10.5m) being made available for innovation in 3D.

The rational side of 3D printing

To his credit, Chris Anderson knows that conventional automation is here to stay. In Makers, he observes that "it’s the only way large-scale manufacturing can work in rich countries". What can change, he believes, is the role of SMEs, which can, he says, "reinvent manufacturing".

This is to get things round the wrong way. In one of the few reports to contain a balanced assessment of the limitations of 3D printing, the auditors and consultants Deloitte reported in early 2012 that sales of both consumer and commercial versions of 3D printers were unlikely to reach $200m that year, and that most revenue would likely come not from consumers, but from the business-to-business (B2B) market.

The figure of $200m sounds small, and could well be a big underestimate. Yet either way, the difference 3D printers will make is likely to be biggest among large firms – including firms that can build whole houses with 3D printing techniques.