This article is more than 1 year old

Infinite loop: the Sinclair ZX Microdrive story

The rise and fall of a 'revolutionary' storage technology

At a stretch

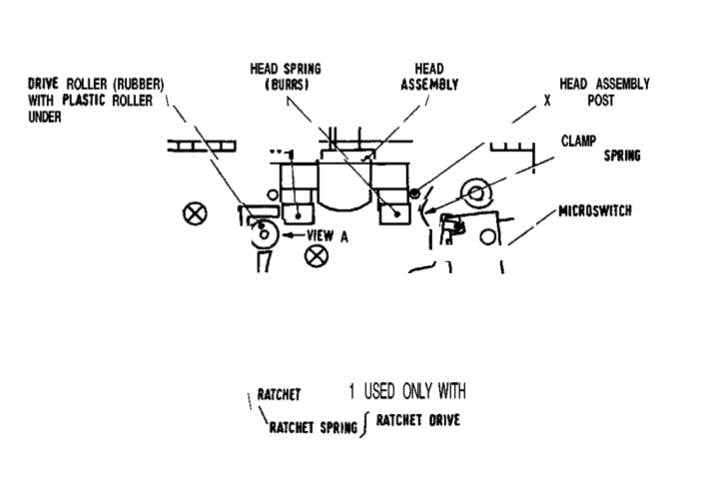

Like all media based on very narrow, thin magnetic tape, the Microdrives accumulated particles of the magnetic oxide material, a problem exacerbated by the need to pull the 2mm-wide tape out of the centre of the storage reel - from where it was fed in a loop over the read head and back to the outer edges of the spool - and the extra friction it induced. The tape was moved by a rubber-wrapped wheel in the Microdrive, pinching the tape between it and a plastic wheel inside the cartridge. Firing up the drive, taking the tape’s speed at the head from zero to 750mm per second, would give the tape a big tug, leading to stretching at the point where the tape emerges from the centre of the storage wheel. Later versions of the drive incorporated a 22µF capacitor to allow the motor to come up to full operating speed more smoothly.

Even Sinclair, in the Microdrive manual, had to admit: “Microdrive cartridges will not last forever, and will eventually need to be replaced. The symptom of an ageing cartridge is that the computer will take longer and longer to find a program or file before loading it. So it is a good idea to keep back-up copies of important programs and files on another cartridge, or on a cassette.”

The Microdrive head mechanism schematic

While the drives were, at £49.95 a throw, considered cheap, replacement cartridges, which cost £4.95 each, were not. That’s about three times the price of a 5.25-inch floppy disk at the time. Storage capacity, initially said to be 100KB, had by launch become “no less than 85KB”, to allow for capacity lost to tiny differences in the length of the tape in different cartridges, motors running at slightly different speeds in different drives and, to a lesser extent, bad sectors on the tape. Each tape stored up to 200 512B sectors spread over two parallel tracks, the drive’s electronics automatically ensuring the correct track was read.

Each cartridge could hold no more than 50 files, and information had to be read into memory, changed, the original erased and the new version written onto the tape. There was no way to modify the files directly, a consequence of the drive’s lack of true random access.

The drives themselves had flaws. Adding extra drives seemed easy: just join them with a ribbon cable that clipped into the side of each unit. But each drive also had to be screwed together using a special bracket - clearly, Sinclair Research was worried that an inadvertently knocked drive would break its connection, crashing the system and potentially losing a user’s data. Up to eight drives could be lined up alongside each other this way.

It was later found that the mounting for the microswitch used to sense whether a cartridge’s write-protect tab had been removed was placed in a way that overly vigorous insertion of the cartridge into the drive could cause the mount to bend, “causing incorrect switch operation”, as a later, October 1985 Microdrive service manual reveals.

Rush to production

“I believe Clive rushed the Microdrive into production too soon, and the variability of the drive heads and the tapes meant reliability was quite spotty. If you went through a few drives, you could generally find a good one,” remembers John Mathieson, in the early 1980s a Sinclair engineer working alongside Ben Cheese and Martin Brennan, though not directly involved on the Microdrive project. He designed the ZX Interface 2, the add-on that would allow the Spectrum to accept Rom cartridges.

As Brennan and Cheese ploughed on to complete the electronics and the software, others under David Southward refined the drive’s mechanical engineering. Brennan recalls a hectic pace - “coming in to work on Saturdays and Sundays; working late most evenings” - but no specific deadline to which they all needed to reach.

Not that there weren’t very difficult challenges to overcome. The promised 100KB capacity was one. Using an analogue storage medium, the tape loop inside the cartridge, meant Cheese had to deal with a frequency response that was not only not flat but varied with the speed at which the tape passed over the read head. Speeding up the tape improves the response, but at the cost of storage capacity for a given length of the material. Getting an even frequency response is essential if the system is to accurately pick up the changes in frequency which encode the 1s and 0s of binary data.

Combine that with the tolerances accepted in the tape length, motor speed and such, and Cheese and Brennan saw considerable difficulty ahead if they were forced to meet the 100KB target. Cheese, backed by Brennan, argued that Sinclair needed to play it safe with capacity, and they were able to convince Southward and Searle that the capacity should be 85KB, with the potential for a higher value if a given tape and drive were in perfect alignment. That’s the capacity that the Microdrive system promised when it finally went on sale in September 1983.

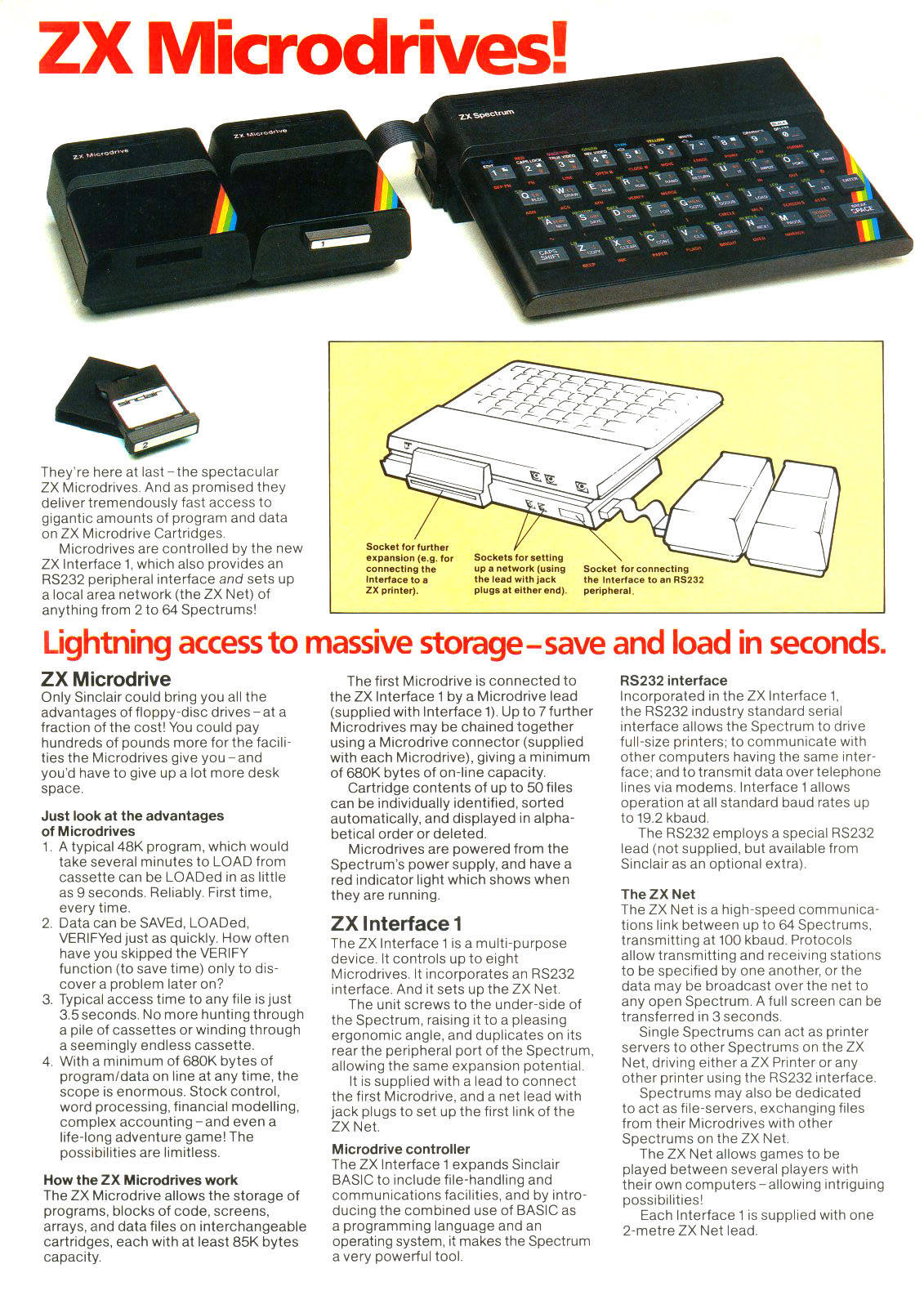

Promoting the ZX Microdrive

The Microdrive soon had competition. US company Astec introduced what it called the Wafadrive in the summer of 1984 - the product was sold in the UK by Rotronics - which comprised a dual-drive hardware unit which took 16KB, 64KB or 128KB tape cartridges. The drives were rather more expensive than the Sinclair offering - £130 for the Spectrum version, or £160 for a unit that connected to the Commodore 64 - but the tapes were cheaper: just £3.95 for the highest capacity. The drives also had Centronics and RS232 ports on the back. Again, each cartridge contained a 5m loop of tape to simulate random access, though the speed of access fell as the capacity increased, as there was more tape to spool through. Sinclair User found the system to be rather more resilient than the Microdrive - mostly thanks to the larger, more robust tape cartridges - but slower.

Of course, what neither system could replace was the audio cassette. For almost all users of Microdrives, the tech became a place to store their own programs and data. Few companies were able to offer software on Microdrive cartridge, at least until the Sinclair QL, which also used the Microdrive, began to sell well. The QL hardware was developed by David Karlin, who sat close to Brennan and was able to get regular updates on the progress of the Microdrives while the machine, originally codenamed the ‘ZX83’, was under development. Likewise Tony Tebby who worked on the QL’s system design and driver software.