This article is more than 1 year old

Space Shuttle Columbia disaster remembered 10 years on

What really happened to the mission that grounded NASA's orbiter fleet?

The Investigation

CAIB (Columbia Accident Investigation Board) initially found it incredible to believe that a foam strike could have caused the tragedy. The results from CRATER simply wouldn’t allow for such a scenario to be possible. It was only after the board looked into the development of Crater itself, that startling information was uncovered. Not all of the experimental results had been entered into the database. In fact, tests with large foam impactors caused such extensive damage to tiles that it could not be measured.

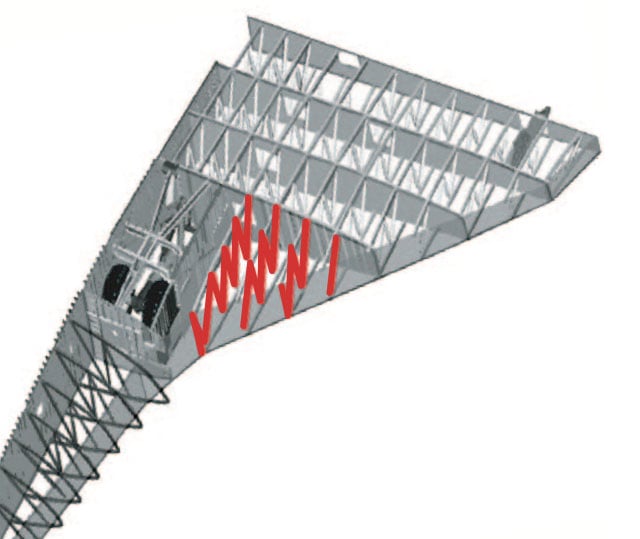

Nitrogen gun used to fire foam at the RCC test rig

CAIB concluded that Crater was only suitable for use with small foam debris, some seven hundred times smaller than the chunk that hit Columbia. Although it was now known that the foam could have damaged the tiles, it was not accepted that damage to the HRSI tiles would have resulted in total loss. Further details of the strike were needed.

Enhanced video investigation methods revealed that the foam did not actually strike the HRSI tiles, but actually hit the leading edge RCC panels considered “indestructible” that had been overlooked previously. Following this revelation, NASA engineers set about building a mock up of Columbia’s wing from spare RCC panels. Using a nitrogen cannon to fire foam blocks at the rig, showed that foam impacts could cause catastrophic failures.

RCC panel damaged in foam impact test

Having finally determined the truly deadly nature of high velocity foam, CAIB found that the damaged RCC panels would have allowed superheated air to pass through the thermal protection system and enter the wing cavity. Once inside the wing structure, temperatures exceeding 3000°F would have made short work of the aluminium framework, explaining the loss of sensors within the wing and destruction of the landing gear. Once the wing was breached Columbia didn’t stand a chance and the entire vehicle soon succumbed to the intense heat.

Columbia wing section indicating area exposed to hot gas in red

Columbia’s doom was ultimately spelled out by lack of communication and refusal to acknowledge the present danger highlighted by those who were in the know. If this sounds familiar, then you are most likely remembering Challenger when it exploded shortly after launch in 1986; very much the victim of the same attitudes.

Descent proposals

Had the peril been recognised, NASA had several options to explore – it would have been entirely possible to rescue the crew, if not Columbia itself. Since the incident, experts have suggested that an alternate re-entry trajectory may have been able to at least get the crew below 40,000 feet at which they could parachute to safety. Such a plan involves a “crabbing” entry, shuffling the Shuttle sideways, exposing the right wing to higher heat loads but preserving the damaged left.

Other options included performing repairs on-orbit and waiting for a rendezvous rescue by Space Shuttle Atlantis, which was on the launch pad at the time. These two options would have required a resupply to keep the crew alive, but this would be entirely feasible with one of many available launch vehicles. While these options would have been incredibly costly, such a rescue would have brought NASA much needed positive publicity in a similar manner to Apollo 13.

Had appropriate action been taken, STS-107 could have been remembered as a triumph, rather than a tragedy. ®

Debris outline collection hangar in 2003: 78,760 pieces identified at the time with over 84,000 pieces recovered later

The full CAIB report from August 2003 can be found as PDFs here.