This article is more than 1 year old

Tell Facebook who's the greatest: YOU are!

Or you can just buy a mirror instead

Opinion HMV called in the administrators on Tuesday, prompting wailing and mourning from thousands of people who hadn't set foot in one of its outlets for years. Sky News brought in Andrew Harrison, the tech-savvy editor of Q magazine, for what I suspect the editors wanted: a simple soundbite on an entire industry extrapolated from the performance of one company. But Andrew is a very smart chap - and didn't quite give them what they wanted. Instead, we got a brilliant summary of what record shops can do - and where they can go.

What online delivery does, Harrison reminded viewers, is get you what you already know you want very quickly. Supermarkets put popular music in your face, at a keen price - but only bring in stock for a very limited range of CDs. As for HMV, it had long ago abandoned music except as a vestigal item: it was actually quite hard to find the CD section in a modern HMV, Andrew pointed out, whereas indie record shops that put music first are actually flourishing. (Rough Trade's second half sales were up 8 per cent - and it's expanding).

But the great thing physical stores gave you, he pointed out, was serendipitous discovery. You'd find something you didn't know you wanted, lured by a great sleeve perhaps, or a good pricing offer. In a physical store, you can browse hundreds of items in the time it takes to load a couple of web pages. Meanwhile the papers are full of stories about HMV "getting its digital delivery".

Very few people seem to have noticed that there's much more to the shopping "experience" (apologies for using the E word) than instant gratification. Now, I doubt Andrew Harrison has much in common with the Mail's grand pontificator Simon Heffer, but the latter does well to sum up the joy of music retail therapy: "I seldom went in with a specific purchase in mind, but always came out with piles of CDs," writes Heffer. HMV had contrived to make music shopping a joyless experience - the wonder is that it lasted so long.

So the joy of discovering pleasure in the unexpected is quite important; it takes you beyond your own immediate preoccupations.

Navel Search?

Now keep this in mind as we look at what Facebook revealed yesterday: its great annual "innovation" - something called "Graph Search". Facebook Graph Search allows you to search a billion Facebook users to find people by their interests and location. It has its uses, for sure, as a kind casual dating service. But what it does really does is ensure that serendipity will never intrude upon your life. It's very unlikely that you'll type "Interests: Bare Knuckle Fighting Place: Romford">" unless you're already interested in bare knuckle fighting. People may use Graph Search if they're new to an area, perhaps, to find friends. But let's not kid ourselves - most people won't.

We've always used to technology to tailor our immediate environments, but this is relatively new and interesting. It's interesting because nobody has asked for it. It's not a product which is fulfilling a real demand. But what's really interesting is how it is so at odds with Facebook's espoused marketing mission: "to make the world more open and connected". Graph Search is billed, without any irony, as a "discovery" mechanism. But what Graph Search does is focus people on their own interests; it makes the world more far more selfish and isolated.

This is a trend I started to identify almost a decade ago, before Web 2.0 even had a name. We have always devised technology that helps us tailor the environment around us - we no longer live in communal homes, we like the comfort of an air conditioned car, and we enjoy immersing ourselves in a book or a piece of music nobody else can read or hear. But this was something quite different.

In theory everyone is more connected than ever, but in practice, it's a Balkanisation of interests: the goal is to bulkwark the Self. The pioneers of social media used it to exclude opinions they didn't like - quite proudly demonstrating their intolerance and control-freakery.

The world is incredibly rich and surprising - but this is a technology designed to find people who like exactly the things you do. It makes the world small and homogenous.

Techno-Utopians wank themselves silly imagining a "Hive Mind" or "collective consciousness", but the reality is the opposite - we're encouraged to become a billion nation states of one.

(Note: I was off by a factor, there. Nick Carr has also written about this very well - and spotted it right away.)

This is territory that film-maker Adam Curtis has covered in greater depth than anyone. His 2002 BBC series Century of the Self looked at how the Freud's ideas were adopted. The most acute film of the four is number three - called There is a Policeman Inside All of Our Heads, He Must Be Destroyed - which looks at how the baby boom children of the 1960s counterculture became the strongest supporters of the individualism of the 1980s. They were looking for Me. They probably still are.

But even Freud's cranky and now discredited model of the human mind was greatly richer than the model Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook presents to us in Graph Search. Freud at least attempted to account for human motivation and agency; Zuckerberg just assumes we want to "discover" what we already like.

Personally, I see no cause for alarm here. Simplistic ideas that narrow our world never succeed. Facebook is only ploughing this rather desperate furrow because the digital economy hasn't matured into a transactional economy yet: giants like Google and Facebook are still dependent on advertising. This has created a sort of derivatives bubble of data-mining personal information. So the tech firms work with what they've got - which is a few interests and affinities.

But we like to be surprised.

Yesterday, the UK government issued paternalistic guidelines on how we should behave on social media - a quite amazing thing when you think about it. This warned us not to use the internet to cause "annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety". But half of Twitter seems to be constantly on the prowl for something to be annoyed about - and take noisy offence at. They're looking to get anxious. Some take this as a sign of intolerance (and of course, it is), but I see it as a sign of boredom - boredom induced by an online world that really can't give us serendipity, a nicer kind of surprise.

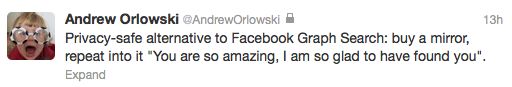

I gave this advice on Twitter yesterday - and I think it's a much more satisfying alternative to what the greatest minds of our generation have come up with at Zuckerberg's Facebook:

What do you think? ®