This article is more than 1 year old

Scoop! The inside story of the news website that saved the BBC

How BBC News Online was created from scratch

The days and months after the successful launch – and attempts to wreck it

Despite early problems, News Online raced out of the blocks. At first it crashed several times a day – but it was up and running very rapidly.

The site started to double its readership every month. Smartt’s team quickly found a voice. The clean look, speedy operation and the breadth of material available reminded people of the scale and reach of the BBC’s journalism. It was definitely British – but the World Service feeds gave it a global feel.

The News Online home page a few days before launch ©Matt Jones

And the journalists were soon showing up their rivals.

“In my own field, science, we were doing it quicker and sharper,” said science correspondent David Whitehouse, who joined the team shortly after launch. “We completely destroyed everybody else.”

The citadel of BBC Newsgathering had initially ignored the newcomer. Before long, it was getting stories by looking at the BBC’s website. “Do you think when you get a good story, you could tip us off?” the head of newsgathering was overheard asking the news website team.

News Online was the first to cover the Ladbroke Grove train crash because, according to one BBC worker, “you could see Ladbroke Grove from the seventh floor where we were based. A puff of smoke went up. The website's managing editor, Dave Brewer, took a camera, took a picture, and we had it up online. We broke the story because he saw the smoke.”

Today there’s a mini-industry urging journalists to "learn to code", but Mike Smartt thought that was an unforgivable a distraction. “No coding was necessary – in fact, the use of HTML by writers became a sackable offence,” he recalled.

BBC News Online scooped the news website category at the BAFTAs in 1998 and for the next three years – until the category was abolished. Even so, another journalist speaking to The Reg said: “It took two to three years before the rest of the BBC realised that online would be just as important as TV.”

But the success brought enormous resentment. The biggest obstacle blocking the team wasn’t technical nor a commercial rival – but the BBC itself.

The Empire Strikes Back

Incredibly, despite the string of BAFTAs, the BBC’s biggest success story wasn’t appreciated.

The BBC’s Online operation, separate from the news website, was located in Threshold House, an overspill office on Shepherd’s Bush Green, where Ed Briffa, chief of Broadcast Online, and his new strategy assistant Azeem Azhar, an Oxford graduate in philosophy, politics and economics who had briefly been a Guardian technology correspondent, worked. The News Online team referred to this as “PowerPoint House”, an indication of the tensions between the two factions.

A snapshot from 1998

The runaway success of Eggington and Smartt’s new operation contrasted with the poorly focussed sprawl of the rest of the BBC’s internet operation. Broadcast Online operations had spent £30m on its sites. Meanwhile, the news website was run on a tight budget, cost a third of Briffa’s overall budget, and was eclipsing it in terms of traffic.

In early 1998, News Online noticed something strange. Server logs showed that all BBC websites had experienced an unusual spurt in visitor traffic. On some days, according to the logs, the most popular domain browsing the BBC was the BBC itself. What was happening? BBC Online had decided to include “non-human page impressions” in its numbers: around 65 to 80 per cent of the "hits" were actually coming from Microsoft and Netscape push channels. Just as sending a letter is no proof of its receipt, most of the subscribers never saw the pages.

The News Online team came under pressure to follow suit – and include its own substantial push numbers – but declined. The independent web traffic auditor ABC noticed the caper and refused to audit the BBC’s numbers.

Briffa departed in 1998, but there was no respite from his successor Mark Frost, an American who joined after a brief stint at AOL UK. Frost was convinced Will Wyatt, head of the BBC's broadcast TV and radio empire, could bring News Online to heel. But because the news website team had carved out its own reporting line – via Abramsky and Hall – at the start of the venture, that was never a realistic proposition.

“There were attempts to broker back room deals to take over News Online, sometimes someone would try to get control of the funding, sometimes asking for access to our database to repurpose news content elsewhere, and sometimes just leaving us to do good work and then taking credit for it," recalled one insider.

There are people who take credit for BBC News Online today who devoted their efforts to trying to sabotage it, one former insider noted wryly.

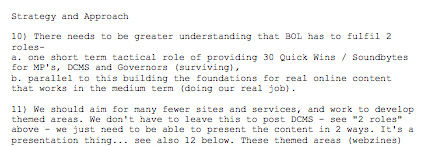

Quick wins and webzines.. a flashback to 1998

A memo to Briffa from his team in 1998 revealed a lack of focus, a craving for “quick wins” and the desire to create a technical bureaucracy.

Yet the BBC’s top brass could see what worked and what didn’t – and News Online worked. Before he officially took office, Greg Dyke – the incoming director general and Lord Birt’s successor – visited Eggington and Smartt, and was impressed. Dyke was actually gauging who was most competent in Online to launch a sport website – which would have been a huge boost in traffic for whichever team won. Dyke was impressed enough to give the News Online team the job.

BBC Sport landed the web news gang another another huge success. Jones gave the sports pages a distinctive yellow background – much like evening newspapers printing Saturday scores on pink paper. The BBC’s first attempt to put the football results online saw them published at midday on a Sunday. It has come a long way since. The success of the sport site ended any realistic prospect of Fujitsu reviving Beeb.com, or the Broadcast team ever finding a hit. The Broadcast Online rivals began to peel away into the private sector – or tried to join News Online.

Karas recalled spending hours discussing URLs with Tom Loosemore, who had joined Frost’s team and was attempting to build a site for the 1998 World Cup. Loosemore was one of several who wanted to switch to News Online. No one could find a job for him in the team. He went on to head a large team devising “BBC 2.0”, which was cancelled, and now works at a vastly expanded Cabinet Office devising "GOV 2.0" – a project to streamline public-sector websites. After months of deliberation, the GOV 2.0 recently standardised on a new font for Whitehall sites, called Transport.

The sports page: the yellow 'un

Briffa’s successor Mark Frost, introduced to the BBC by Azhar, lasted a year. BBC Online staff drifted away to cast their lot in the first dot.com bubble. Azhar himself would start eSouk, a short-lived incubator.

“I warned the news website team from the outset that their startup wouldn’t last. As the News Online site became more vital to the BBC, it was inevitable it would be brought back under central control,” recalled one executive.

Having seen off the worst of the threats, and with News Online now a core part of the BBC, Eggington moved on in 2000. Karas joined a spinoff of Mike Lynch’s Autonomy. Mike Smartt led the editorial team until 2004, and was made an OBE that year.

What made it succeed, then?

“Apart from the well-matched team, the simple truth is that we had a clear and valuable mission, while something like the EastEnders discussion forum didn’t," said one former executive. "People came to the BBC website for news and sports – which is news – or for programme information. Now they come to watch a program. Everything else, the vanity pages, is cruft.

“Bob [Eggington] put up a wall around the team stopping harmful external interference. We would offer to help other departments but it had to be on our terms. We ended up helping World Service quite a lot."

The site had a clear focus, and it focussed relentlessly on what the licence-fee payer really valued from a BBC site: reliable news trickling in over a slow dialup link.

“In those days nobody really knew what they were doing – it wasn’t unusual for half the budget on a project to be wasted, or 80 per cent. We had a very clear idea of what we needed to do,” Eggington said.

Karas agreed that it’s the lack of focus that explains why generously funded web publishing projects fail: they hire talented people, but don’t tell them what is needed.

“It's as though people think that the ingredients for a good web operation is hiring well-known website builders, rather than having a vision for some useful, informative or entertaining content," he said.

That’s a little bit like starting a newspaper by hiring some printers and telling them to print a newspaper. When it doesn't work out, it's not the printers' fault".

All three executives were driven to make it succeed. They also knew how to defend the fledgling operation from the BBC bureaucracy. And there was a huge element of trust down the chain of command. Lord Birt trusted Abramsky, and Abramsky trusted Eggington and Smartt to deliver, and fought their corner for them in the boardroom.

A huge degree of trust was placed on the techies to build the world’s most demanding news content management system – which paid off. And this trust was also enjoyed by correspondents, who were proud of their role in the system and were highly motivated. “They gave creative people what they need, a bit of space,” recalled one reporter.

And the quality of the staff was excellent. “BBC managers aren’t always very good – but Bob Eggington and Mike Smartt were exceptionally good managers,” said Whitehouse. Eggington himself says it was simpler than that:

“We wanted the best thing from a user’s point of view.” ®