This article is more than 1 year old

Liberator: the untold story of the first British laptop part 2

Out to launch

The Liberator lives... almost

Both Terry and Williams insisted on a large display - notable at a time when past mobile computers, especially those he had evaluated in a bid to find a suitable machine for his Civil Service colleagues, had either tiny screens or wide, but shallow displays. The need to include the big screen - a Toshiba-made 80-character by 16-line job with a pixel resolution of 480 x 128, supplied without a display controller so Jan Wojna had to design one and build it into the FPGA; comparable products had 40-character by eight-line screens - almost certainly inspired the Liberator's clamshell design.

Derek Williams handled with the Liberator’s industrial design. The six-month design and build timeframe made gearing up steel tools for the machine’s injection-moulded case impossible to achieve, so Williams sought out firms who specialised in aluminium tooling and had experience in injection moulding. “Steel tooling would have take three to four months to prepare,” he says, “and that would not have worked for us. We needed to be able to develop the mouldings very, very quickly.”

The 'CMND' key was crucial...

Williams approached the Production Engineering Research Association - now simply Pera - in Melton Mowbray, and Pera put him in touch with a consultant to work on the Liberator. “But they like steady, stable projects, and they weren’t used to pressure and constant revisions, and the guy working on the design and the tooling, he couldn’t handle the stress.” Williams began to search again, and found a Gloucester-based designer called Miles Bozeat. “He had experience in aluminium tooling, he was a very innovative designer. He took the project over from Pera.”

Bozeat came up with various designs, not only the angular look that was ultimately adopted for the Liberator but also a more rounded case which, Williams recalls, was the one favoured by Bernard Terry. But it was veto’d by the Thorn EMI marketing department, which favoured the “more contemporary” look that the machine eventually shipped with.

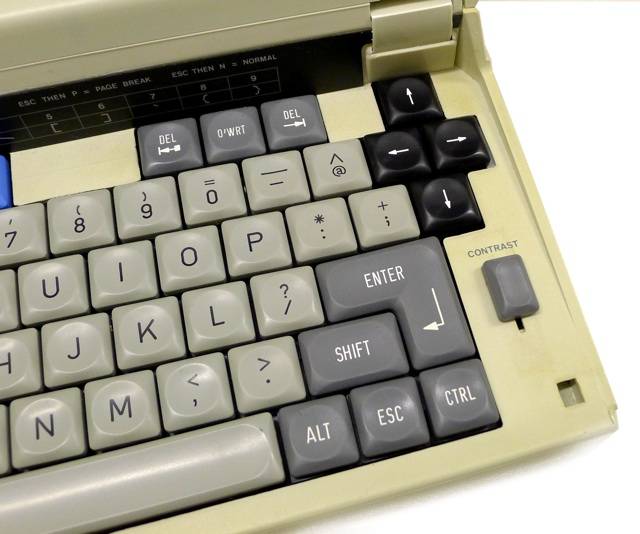

The Liberator, then, was a surprisingly thin and light machine, cased in cream plastic, with hinge half way along the top surface. Release the black catches on the left and right sides, and the forward part of the upper case springs up to reveal the 62-key keyboard, a slider control to adjust the screen's contrast, and the machine's monochrome LCD screen. Displayed around the panel: character- and line-count rulers, a nod toward the typewriter's formatting aids.

Knee-friendly underneath?

The rear of the Liberator, which is where the majority of its ports were located, was protected by a plastic strip that could be pulled away from the back of the machine to form a carry handle. Fold the handle down and it became the laptop's stand. Rotate it the other way, up and over the top of the machine, and it became a support for the display, which would otherwise fold to lie back flat onto the top of the portable.

The screen had no fancy hinge, simply a thin - but durable, if surviving Liberators are anything to go by - plastic strip connecting the separate display housing to the body of the laptop, and containing the screen's signal ribbon cable and power feed. Pulling the handle away from the back of the machine exposed the Liberator's removable 9V battery pack, its two 8-pin, 9600 Baud Din-type serial ports, and a parallel Ram expansion port. There was a second, general-purpose parallel expansion port on the Liberator's left-hand side.

The Din ports were based on a specification called S5/8 - for 'Serial five Volt, eight-pin'. Its use had been proposed by the Public Service Working Party (PSWP), under the recommendation of Technical Consultant Andrew Hardie and others. The PSWP had found RS232 to have become a "plethora of incompatible sub-sets" of the standard, while an alternative interface, the Centronics specification, was impractical for mobile use because of its "expensive and even larger multiway connectors". So the PSWP devised S5/8, which would, the organisation believed, provide a simple, low-cost and low-power alternative ideal for mobile computers. It pitched S5/8 to the British Standards Institute (BSI) during 1984, and the technology was subsequently added to the Liberator specification.

...but the Contrast control never quite overcame the LCD's limitations

The PSWP's motives may have been sound, but it proved a mistake for the Liberator. As reviewer Nick Walker noted in his evaluation of the Thorn EMI Machine for the September 1985 issue of Personal Computer World magazine: "It's doubtful this new standard will be adopted by printer manufacturers... Even Thorn EMI's own printers, especially selected for the Liberator, are Centronics machines with the necessary conversion box."

Specifications later suggested for next-generation Liberators would feature Centronics port.

The first Liberator's on-board memory was segmented into two banks, A and B, containing 40KB and 24KB, respectively - 64KB in total. There was a further 8KB of Ram on board for system use, but only the amount of user-accessible memory was stated in surprisingly honest promotional material. Flip a slider switch on the back, and bank B would not only kept powered by its own battery, but write protected like a diskette. Both banks were also fed from the main battery even when the Liberator was turned off, allowing their content to be retained - an amazing innovation in an era when most computers used floppy disks for non-volatile storage, hard drives were simply too big and too power hungry for a portable, and Flash solid-state storage was the stuff of dreams.

Even if the main battery ran flat or was removed, memory bank B's contents would be preserved by a built-in button cell that provided 50 to 500 hours' data protection, Thorn EMI claimed at the time.

The two ports are the Din-based S5/8s, the would-be UK standard

According to the Liberator manual - preserved, along with a machine and many of its peripherals by the Science Museum - the machine's "memory is allocated in 'blocks' of about one thousand characters". Two blocks were assigned to the word processor's paste buffer. Linney recalls that memory was implemented in Static Ram because it consumed less power - energy wasn't expended regularly refreshing each memory cell's state.

Not every machine came with Bank B. Two models were put into production: the 40KB LPTP1001 and the 64KB LPTP1002. The former only had Bank A fitted, the latter Banks A and B. Both banks were separate, as was Bank C, added to either machine plugging the LRAM1060 24KB Ram pack into the Liberator's expansion port. It too could be write-protected and kept powered with its own on-board battery, allowing it to be used to swap files between machines.