This article is more than 1 year old

Atari Pong at 40: Alcorn talks plastics, pirates and square balls

Pong pioneer to Bushnell: 'Screw you, I'm not making it round!'

Unintended success

Pong the home game had been in the frame from day one for Bushnell, but it was Pong the arcade game that started priming the demand three years earlier, in 1972. The arcade game, though, might also never have happened. Bushnell had hired Alcorn to build a better Odyssey after, legend has it, he attended a demonstration by Magnavox on 24 May, 1972. Bushnell founded Atari on June 27. Magnavox later sued Atari, along with others, for patent infringement.

The problem for Bushnell was he didn't have sufficient cash to invest in a home system in 1972; he had just $500, according to Alcorn, who became Atari vice president of R&D and after leaving Atari became an Apple fellow. "Doing a home game was way out of the question at that point in time for us. It cost too much money to make a chip. We didn't have any money," Alcorn told us.

Instead, Bushnell fell back on what he knew best: arcades. Bushnell had worked at an amusement arcade in Salt Lake City during his university years and had been inspired by Steve Russell's Spacewar!. Alcorn said: "He [Nolan] said: 'There's a game: if I can put that in an arcade where pin ball machines were, I could make a lot of money'."

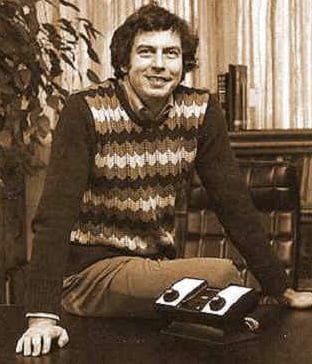

Bushnell and Alcorn had met working at video and audio equipment manufacturer Ampex. Bushnell gave Alcorn, a recent graduate, the job of building Pong simply to get him up to speed on video game programming – a new field at that time. Bushnell, it seems, had underestimated just how driven Alcorn would be in delivering arcade Pong.

Nolan Bushnell: Arcade-turned-Atari man

"I got to work on it and that's the prototype I created in three months," Alcorn told us, gesturing towards the original machine, now sitting behind glass in the renovated Computer History Museum off the 101 freeway in Mountain View.

"I was disappointed because it had too many chips in it. Nobody told me it was going to be a throwaway. The real game was going to be a more complex game, but he [Bushnell] didn't tell me that. So I added speed up and sound and other features to it to make it playable. We put it in that cabinet over a weekend and put it in a bar [Andy Capp's Tavern in Sunnyvale]. It was a big hit.

"I was thinking: 'Who the hell would play this thing? It says Pong, there's a coin box on the side, there are no instructions and it requires two players.'"

As it happened, plenty of people wanted to play Pong, as Alcorn discovered when he got a call from the manager at Andy Capp's Tavern after just a single day – to say the machine had broken and that it needed fixing. When Alcorn arrived at the bar, he quickly discovered that the "problem" was the machine simply couldn't take any more money: the slot was overflowing with quarters. From that first machine to the last, Pong reputedly made four times as much money as other coin-operated games, with Atari selling more than 35,000 of the units.

Raunch-free

What accounted for Pong's early and unexpected popularity? Game play, yes, but also the casing of that humble and unassuming wooden box Alcorn had hurriedly assembled over the course of a weekend. There was a thriving business at the time in ornate fantasy art for arcade game casings. The understated design had helped pulled in a new group of gamers, one which is still in demand and which companies such as Nintendo and Microsoft have tried to lure with the Wii and Kinect: women.

Alcorn tell us: "We knew the game had to last for about a minute or two and Nolan wanted it to be a subdued cabinet. Back in those days the pin ball machine" – the staple of bars and amusement arcades immortalised by Elton John – "had lurid pictures of ladies and tits on them, and Nolan wanted [Pong] to go into bars and other locations that would appeal to women. I think this became a very good social game because women could play it because it wasn't biased sexually."

Atari quickly saturated its market, becoming as big as the dominant arcade games company of that time, Bally, giving Atari the money and motive to get into the home. Bushnell's company had a turnover of $40m in 1975 – with $3m profit. Also, clones were becoming an issue: Pong's architecture of 66 chips on a board programmed using discrete logic was easy to knock off. Soon, boards were coming from Chicoin, Meadows and Ramtek with even Bally offering its own Pong, called Pong Playtime.