This article is more than 1 year old

How big telcos can repel the Valley's OTT insurgents

And why they probably shouldn't try

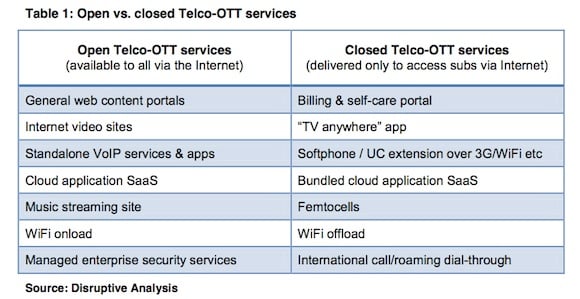

Part two After years of bouncing around PowerPoint slides, the battle between telcos and "Over The Top" insurgents is now very real. It's a scrap that's characterised as Silicon Valley upstarts storming the gates of the closed network world, and that's not a bad nutshell introduction. Long-time OTT champ Dean Bubley of Disruptive Analysis calls these insurgents "access-independent internet services".

Traditionally the telcos have been dependable and profitable, but innovation-averse. Internet companies sometimes have good ideas - but they're anything but dependable and rarely profitable.

The vast profits that telcos make today - over $150bn in revenue from text messaging alone last year - look like low-hanging fruit. Thanks to smartphones, data plans and a flourishing app market, punters are voting with their feet. For example, OTT insurgent Pinger, popular with US teens, has become the country's seventh biggest operator purely on the back of its apps.

All of which sounds quite dramatic.

But if anything, the Valley-versus-dinosaur description underplays the nature of the disruption: this is more than a cultural or a technical skirmish. It's about whether telecomms companies, which today are vertically integrated money-making machines, can adapt and become "platforms" for third-parties, without hollowing themselves out.

The range of predictions I've canvassed for this special report is very broad, but at least there's some agreement on what is the nature of the battle.

One perhaps surprising admission this week came from Vodafone's CEO Vittorio Colao. He admitted that OTT players drive traffic to telcos - so this isn't a story that necessarily ends with the winner holding up the severed head of the vanquished. Both sides in the OTT battle could benefit.

In part one I looked at a fascinating company called Tyntec, which sits as a gateway between the closed telco world and the upstarts - and outlined some of the new services. But what there are plenty of pitfalls before this is resolved. Some could be fatal. So let's see what these are.

Fear the regulator

The idea of "regulatory capture" was coined by public choice theorists in the 1950s, and helped win a Nobel Prize for Chicago School economist George Stigler. In brief, new market entrants come out worse in any competition for a regulator's scarce time, while profitable incumbents with deep pockets "capture" a watchdog and win favourable regulation.

One example is the distribution of real telco-world phone numbers that are used as the bridge to internet-connected services. These, as we saw in part one, are really critical.

"Dishing out number ranges is jealously guarded," agrees Bubley. "If you're a mobile operator, your block of the number range is vigorously defended. These guys spend a lot of money on lawyers to lobby Ofcom deciding how they're allocated."

It's still early days. OTT players acknowledge that the regulatory picture isn't clear - but say uncertainty and ambiguity are more of a problem.

"Virtual numbers are legally a grey area. It's ambiguous. So there's a risk to being first," Tyntec told me.

Germany, for example, insisted mobile services could only be sold attached to a real, physical SIM card. Every mobile number had to be traceable; it was illegal to offer a mobile service without a SIM card. In March last year, it relented. Virtual numbers are now fundamental to bridging the telco world with the IP world.

"In the UK it's not clear but Truphone is allowed, which is promising," Tyntec added.

Europe has 27 national regulators - which makes for 27 different interpretations of whether a mobile number should be attached to a SIM card for example. This doesn't make it impossible to launch, but does increase the risk, and adds an administrative overhead.

But there are are many ways the Empires could strike back.

Nice business idea you've got here. Shame if anything happened to it

In 2005 US regulator the FCC took decisive and pretty swift action against a telco called Madison River, which was blocking VoIP calls (telephony over the internet). Madison River had to pay a fine and promise not to do it again. Although the net neutrality debate rumbled on for years, it cleared the paths for VoIP providers.

There's little to stop a mobile operator blocking outbound calls from a smartphone app, or deciding to not divert them to virtual numbers. But it lacks a legal foundation. And we'd hear about it pretty quickly, whether it was a small operator such as Pinger, or a Facebook or a Google.

More of threat, perhaps, is an incumbent's market power that can be used to innovate just a little, enough to offer punters many of the benefits of the OTT players, while keeping hold of its subscribers. Sky and T-Mobile have done this quite successfully.

Like Tyntec, Vivox is another quite intriguing and game-changing player. It was founded by VoIP big mouth Jeff Pulver, who got got investors to put their money where his chops are, by co-founding Vonage. Vivox began life providing voice chat and IM backchannels for online multiplayer gamers (including Sony Entertainment) and Second Life. But now it offers "softphone" services, which work with carriers. And like Tyntec too, it stresses the opportunities for carriers.

It won a significant prize when it landed T-Mobile. Deutsche Telekom's mobile service uses Vivox for a service called Bobsled, which aggregates a lot of the services offered by OTTs, such as virtualised numbers, "follow me" services, and the like. It's pretty ambitious: telephony escapes the device you're attached to or your social network. Telefonica's O2 is dabbling with JahJah to provide something similar.

For STL Partners' analyst Keith McMahon, much of the OTT hype is unrealistic, and pundits who predict the incumbents will be overthrown are "smoking crack".

"The telcos simply dropped their prices to fend off the VoIP services. Many already route their calls over VoIP anyway," he said.

Equipment manufacturer Huawei now provides a rich platform for punters to create OTT-like services, he points out. Sky uses Huawei for Sky Talk, providing calls for £5 a month to 30 countries, and follow-me services that OTT upstarts tout.

"These are huge platforms with tons of features," he points out. 4G LTE mobile networks will be "all IP" networks too - making it easier to deploy and integrate new features. In theory, at least.

Both acknowledge one point, that what works in the US won't necessarily work here.

Recall Pinger, which collects termination fees from sent messages and shares them with the OTT player and the carrier. But termination rates vary around the world and in many countries the perception is that a mobile number is more expensive to call than a landline. In the US, all numbers are geographically anchored, so the distinction doesn't exist.

"There's a lot of psychological attachment to those fixed and mobile numbers in Europe - and most of the world," agrees Bubley. "You don't send a text to a fixed number."

This might change over time as people begin to 'trust' these strange-looking new numbers. (You can see how much scope there is in the international country code allocations here.)

With the OTT insurgency in its early days, and a significant chunk of the population resisting smartphones, it's impossible to pick winners. Telcos may find it easier to accommodate the new world, opening up to gateways providers such as Tyntec or partnering with companies such as Vivox, and capturing a bit of value, rather than resisting the tide. ®