This article is more than 1 year old

Voyager probe reaches edge of Solar System's 'bubble'

'Soon we find out what interstellar space is really like'

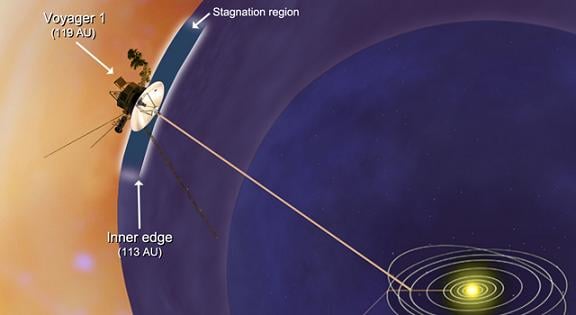

NASA's famous Voyager 1 space probe, sailing outwards into the interstellar void far beyond the orbit of Pluto, has entered a new and never-before-seen region of space thought to be the very edge of the "bubble" maintained around the solar system by the power of the Sun.

"We shouldn't have long to wait to find out what the space between stars is really like," enthuses Ed Stone, Voyager project boffin.

Her 39-year-and-counting mission ... to boldly go

The probe has been encountering strange, previously unseen phenomena in recent times as it comes to the true edge of the solar system, where the "wind" of particles blowing out from the Sun is no longer steady - and sometimes is overcome by the cosmic winds of the wider galaxy, actually gusting back on the outward-bound probecraft.

"Voyager tells us now that we're in a stagnation region in the outermost layer of the bubble around our solar system," says Stone.

"We've been using the flow of energetic charged particles at Voyager 1 as a kind of wind sock to estimate the solar wind velocity," says his fellow Voyager scientist Rob Decker. "We've found that the wind speeds are low in this region and gust erratically. For the first time, the wind even blows back at us. We are evidently traveling in completely new territory. Scientists had suggested previously that there might be a stagnation layer, but we weren't sure it existed until now."

According to a NASA statement issued yesterday:

Voyager has been measuring energetic particles that originate from inside and outside our solar system. Until mid-2010, the intensity of particles originating from inside our solar system had been holding steady. But during the past year, the intensity of these energetic particles has been declining, as though they are leaking out into interstellar space. The particles are now half as abundant as they were during the previous five years.

At the same time, Voyager has detected a 100-fold increase in the intensity of high-energy electrons from elsewhere in the galaxy diffusing into our solar system from outside, which is another indication of the approaching boundary.

Voyager 1 was launched stop a Titan/Centaur rocket stack on 5 September 1977, just two weeks after its companion craft Voyager 2 (launched on 20 August 1977), designed to take advantage of a rare conjunction among the outer planets which would let them make a lot of visits there over a relatively short time without much fuel. The two craft made many discoveries, and Voyager 2 remains the only spacecraft ever known to have visited the outer planets Uranus and Neptune.

But in 1989 their work among the planets was done and the two craft were formally tasked to head out into the interstellar void. For the past 22 years they have been not merely space probes but star probes. Voyager 1, the furthest out, is now some 11 billion miles out, almost 120 times as far from the Sun as Earth and several times as far out as Pluto. Voyager 2 is not far behind at 9 billion miles.

Despite their great longevity, the two craft still each generate more than 300 watts of power from their nuclear radioisotope generators, enough to maintain communications and control, and keep some instruments in operation. NASA's Deep Space Network ground stations around the world are in touch with them 8-12 hours a day. The Voyagers' data links deliver upload rates of 16 bits/second, and download at 160 bits/sec (or 1.4 kbps for high-rate plasma data). When out of communication with Earth, the probes store information on an 8-track digital tape recorder.

There's more on the latest from Voyager 1 here and more on the Voyagers in general here. ®