This article is more than 1 year old

How digital audio ate itself and the music industry

Part One: The birth of a new science

Special Report Digital audio began life with high ideals and worthy engineering feats, with its extended dynamic range came the promise of noise-free recording. This is a story of how it first charmed and then choked the industry it was designed to enhance.

It's a long and complicated story, full of challenges and unforeseen consequences. In the first part, I'll explain how some of the strange choices were made by the earliest digital audio engineers.

It's 1987, and London Zoo is playing host to a conference called the Digital Information Exchange (DIE) run by HHB – a professional audio hire and sales company. Theoretical papers are being delivered and real products are being demonstrated from the leading lights of the era, the likes of AMS and Fairlight.

But there's an excitement to the event. Something new is emerging, finally. The talk of the show is a brand new digital stereo recording format and milling around me are audio engineers of a quite different nature to the ones sat in studios. These guys are behind the designs of digital recorders, including the multitrack machines that would become the mainstay of well-heeled recording studios for the next 10 years. The fruits of their labour are on display and the future looks bright.

Mitsubishi's X-880 ProDigi 32-track recorder

Looking back, 10 years doesn’t seem long enough to recoup all that technological effort, but it was a necessary step that would eventually take us to desktop music-making and with it, a mass culling of professional recording studios. Song demos and remixes that would once keep a studio busy as a 24-hour concern, were lost to the bard in the bedroom and, inevitably, whole albums would be made by musos sitting around in their underpants.

Digital audio itself wasn't new, of course. The compact disc was already done and dusted as a consumer product by the early 1980s, along with digital recording in stereo in the studio to facilitate CD masters. Yet on show at the DIE was the means to bring CD-quality audio beyond stereo mastering and use it for the actual track laying in the studio. Admittedly, the phenomenally expensive 3M systems had already captured performances of jazz and classical works along with Donald Fagen’s The Nightfly, years earlier, but here in the flesh was a new generation of digital multitrack recorder, not some technological rarity.

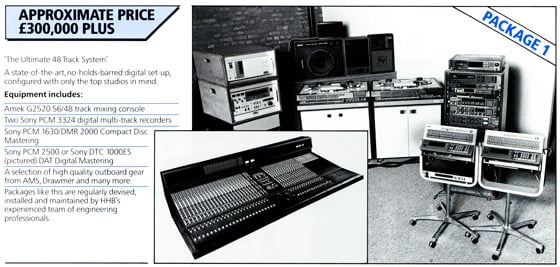

Readily available for hire or sale, these Japanese reel-to-reel digital tape machines were capable of recording 24-tracks (Sony DASH) or 32-tracks (Mitsubishi ProDigi) on one-inch tape. They were still phenomenally expensive but they were impressive – Sony would later double the track count to 48 and license its technology to analogue multitrack stalwart, Studer, once considered the Rolls Royce of reel-to-reel recorders.

Two Sony PCM-3324 DASH machines with mixer and digital mastering gear package from 1987

Although these two tape standards, DASH and ProDigi, were incompatible, they were nonetheless remarkable examples of data storage and precision timing. With analogue-to-digital (A/D) and digital-to-analogue (D/A) converters for each track, these multitrack recorders also featured digital outputs that conformed to one protocol, the AES/EBU standard. And this was crucial: digital interfacing was the conduit that enabled these recorders to speak unto other digital recorders and mixers. What we take for granted with a multichannel Toslink optical cable on the back of a AV receiver today, was in embryonic form here on XLR jacks and, in the case of MADI (multichannel audio digital interface), BNC connectors.