Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/05/20/china_firewall/

Using the internet in the People's Republic of China

Our man reports from inside the Great Firewall

Posted in Networks, 20th May 2011 12:30 GMT

China makes no secret of its desire, and ability, to control internet access, but even at a glance it's clear that the Great Firewall Of China leaks like the proverbial sieve.

We had the chance to try our hand at breaching that wall on a recent trip to visit Huawei in Shenzhen. Our hosts kindly supplied us with China Mobile SIMs for data access so we could see the internet as the Chinese see it, and we managed to test out wi-fi connectivity at a local hotel with similar results - only the hotel wi-fi didn't kick us off entirely for asking the wrong questions.

Cisco provides the racks of servers used by the Chinese government to monitor, and block, access to specific services and information. Unsurprisingly the system is easy for the technically literate to circumnavigate, if we'd been using a UK SIM then our traffic would be routed via the UK operator and thus past the firewall. Even without paying ruinous roaming rates it's not difficult to do most things, though the blocks still crop up often enough to irritate if one is used to unfettered internet access.

Social networking? Ah, you mean QQ

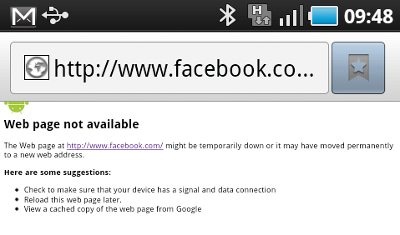

The blocking is almost entirely HTTP related – specific websites are disallowed on the basis of their URL. That includes services such as Facebook and Twitter, but only the websites; the westerner travelling in China will have no problem using app clients out widgets over hotel Wi-Fi and cellular, though the Twitter (SMS) short code won't forward.

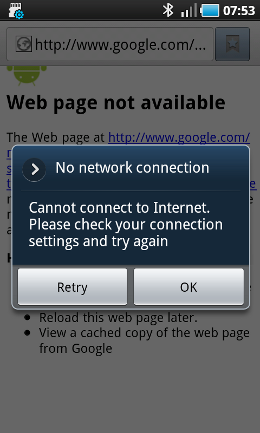

The same rules apply to email. Encrypted IMAP works fine, and Gmail continues to synchronise with it's Android (our similar) client, but try accessing any part of Gmail, or any GMail-hosted service (such as the El Reg mailboxes), on a browser and the Chocolate Factory's email service is permanently off line.

Attempting to load any of the prohibited web sites results in a 'site not found' error, just as if one had mistyped the address or Twitter.com just didn't exist. Locals were aware of the blocks, but didn't consider it remarkable and simply pointed out that all countries block content that they find socially unacceptable, it's just a matter of where the lines are drawn.

More interesting were the results of a contentious search. Google's URL forwards to Hong Kong from China, and mostly works, but search for "Tiananmen Square" and suddenly the cellular connection drops out entirely and has to be reconnected, not a browser error but a disconnected data session. Spell "tanaminm" badly enough and the firewall will miss it, but Google will correct the spelling and return the search results. That's not very useful, as clicking on any of the pertinent ones will result in the "site not found" error popping up again.

Your mobile data connection may be affected

After performing several such searches our cellular connection started playing up quite badly, dropping out at random and requiring a complete power cycle of the dongle before we could reconnect. There's no way to tell if that was down to our activities, or unrelated, but one did follow the other.

Tiananmen what?

China reckons that its site-blocking is no different than our own attempts to block sites hosting child pornography, albeit on a larger scale. But the comparison isn't really fair – at least not yet. We block child pornography because of the harm its production does to children, but moves are afoot to widen the UK's own firewall, and if that's allowed to happen then it becomes harder to attack China's on ideological grounds.

Using the internet in China you might never be aware of the blocking in place, and with a minimum of effort the visitor can participate in most online activities without significant impediment.

The decision to block services that can't be controlled, such as Twitter, has been enormously helpful to domestic versions and is increasingly looking like a trade barrier. In response to such an accusation the Chinese declare themselves happy to have Twitter locally just as soon as the company agrees to implement suitable censorship measures, and Facebook is rumoured to be about to launch a localised (and censored) version.

One could argue that using spurious national-security arguments to impose an unreasonable burden on foreign companies to the benefit of local competition is no different than what the US senators tried to do.

Had the congressmen succeeded in requiring operators to report all Huawei and ZTE kit used in critical locations, it would have been of a huge benefit to companies not in China. The difference, of course, is that the move failed, while in China domestic versions of Twitter and YouTube are thriving. ®