Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/03/03/bt_milton_keynes_fibre_to_the_premises_trial/

BT fibre-to-the-premises trial takes 7 hours per install

Fingers, blowers and splitters in Milton Keynes

Posted in Networks, 3rd March 2011 12:08 GMT

Knee deep in cable BT's new fibre optic upgrade is delivering better real world speeds than the company's old copper-based network when compared to advertised "up to" broadband rates, according to the latest figures from Ofcom.

Meanwhile, the UK telecoms giant is continuing to test out its latest fibre-to-the-premises (FTTP) kit. As part of that process, BT invited The Register to visit its Bradwell Abbey, Milton Keynes trial site yesterday, to look at how the firm is reshaping its cabling infrastructure.

Intensive manpower is required to get the work done but access to individual premises and estates remains a constant challenge to getting the kit installed. BT has 32,000 engineers on its OpenReach books, all of whom are currently re-skilling to help roll out the telco's new fibre technology.

BT is anticipating having to overcome local opposition to its plans to push FTTP cabling under and sometimes over streets throughout the land as it attempts to get its £2.5bn 100Mbit/s downstream broadband fibre optic tech rolled out to two-thirds of households and businesses by 2015.

It has already faced similar upgrade roadblocks from its fibre-to-the-cabinet (FTTC) trials in recent years, which forms part of what the firm as described as a "mixed economy exchange".

Muswell Hill resident Johnny McQuoid, who just so happens to be BT's "superfast" broadbrand programme director, told El Reg that the company was still waiting for clearance from local authorities in Haringey to let the company install 18 of its cabinets in the conservation area of six streets around Queen's Avenue.

BT has come up against less opposition in Milton Keynes, however. In fact McQuoid claimed that the local authorities there had been very helpful during the trial upgrade, with fibre being overlayed on the company's existing copper-based network as well as Virgin Media's television coax cabling in the Buckinghamshire town.

So far the FTTP infrastructure has "passed" 11,500 homes and businesses in Milton Keynes and testing has gone smoothly in the area, said McQuoid. BT uses the "passed" terminology to point out that its infrastructure sometimes passes homes that don't have a copper line.

By September this year BT is hoping to have 12 exchanges built that are kitted out for the new fibre network.

BT said that currently four million homes and SME businesses in the UK could access the service. McQuoid explained that the company was at a run rate of about 300 cabinets per week and was "passing" 75,000 to 80,000 homes and businesses per week.

Ducts, telegraph poles, manifolds, splitter nodes and a very steady hand

BT said it's taking seven hours on average for two of its engineers to complete one "managed install" of the new kit at a customer's home. The company is trying to push the work down to around four hours, but it hasn't nailed that yet during the trial.

Furthermore, the telco can expect bigger challenges when it begins dealing with much older infrastructure than the relatively well-planned duct system in place in Milton Keynes.

Once a customer signs up for BT's FTTP service, the firm's engineers arrive on-site and proceed to blow fibre through to the punter's home. It's a fiddly task involving lots of spliced fibre that is threaded through to an outside connector, which in turn feeds into a BT-branded box inside the house.

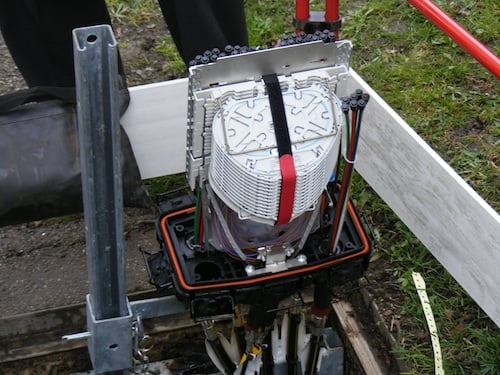

Splitter node – where the magic happens

The fibre is installed from BT's exchange down to a device called a manifold that resides in the ground or up on telegraph poles. But it's a lengthy process.

Cables containing individual fibres are fed out to a splitter, where engineers then splice it and split it to provide the service to up to 32 customers.

The difficult part for the engineers is in getting the fibre pushed through the tubes via narrow subducts that are already used for existing telecoms infrastructure. BT said that the cabling has to be pulled through by hand as there is no tech in place that could somehow automate the finger-freezing process.

BT kit loaded onto vans for FTTP deployment

To put that into perspective, in the Milton Keynes area alone, BT has distributed 600km of cables and around 4,000 manifolds for the 11,500 homes it has "passed" so far.

Once the cable reaches its destination point, BT engineers then blow the fibre through duct tubes using compressed air. The endgame involves connecting up the splitter to the distribution point, which in turn is plugged into the manifold before finally being threaded through to a customer's property. It's a process known as splicing.

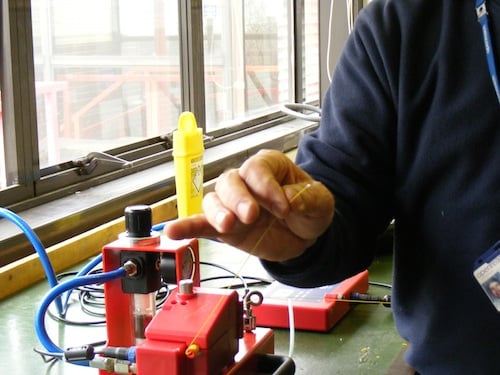

Fibre splicing

An engineer has to strip off the fibre's colour-coded protective coating to get to the delicate, hair-thin piece of cable. It can do nasty things to an engineer if it breaks and gets lodged in their skin.

Once the fibre is exposed, the engineer cleans it with rubbing alcohol and then uses a box excitingly dubbed a "fusion splicer". The device helps to line the cable up and then sticks the two ends together. The ends, guided by the box, have to be lined up accurately, otherwise it flashes a red light confirming that the engineer needs to realign again.

The cable then gets blown into a customer's home and "hey presto" they are given access to BT's fibre network that offers downstream broadband speeds of "up to" 100Mbit/s.

No wonder then that the process is a lengthy one. BT has committed huge man hours to the project, while its main rival Virgin Media says it sees "no compelling reason why" it should heavily invest in FTTP at this time.

For BT, the Milton Keynes trial remains purely a testing ground for now. It is possible that the procedure could change once the company begins rolling out its tech to other regions in the UK. And it's important to note that customers will not be able to choose how fibre is delivered to their home or business. Depending on the infrastructure, they will either get fibre-to-the-premises or fibre-to-the-cabinet.

Beyond that, BT faces local opposition to its OpenReach vans "swamping" streets, estates and businesses as its engineers grapple with all that fibre. It's also getting negative vibes from grumpy landlords too. Ultimately, no matter how exciting the idea of "superfast" broadband might seem, there's a truckload of red tape to cut through first. ®