This article is more than 1 year old

McNealy to Ellison: How to duck death by open source

Ex-Sun boss talks code, community, and underpants

Yes, we have no Solaris on x86

"We had some execs who kept saying: 'We are not going to do Solaris on Intel.' I said: 'Time out, yes we are'. And they'd say: 'We are not going to do Solaris on Intel' and I'd say: 'Time out, yes we are' until we got rid of them. That was probably bad leadership on my part."

This leads us to the other problem for Sun, Solaris and Intel: Microsoft.

Sun should, McNealy told us, have sold and supported Solaris on its own x86 hardware. Instead, Sun took the fatal decision of outsourcing that role: it placed its trust in OEMs such as Dell to sell and support Sun's Unix on their Intel boxes. Problem was, these were the very same OEMs who, it emerged during the US Department of Justice's (DoJ) antitrust prosecution of Microsoft, had had their arms twisted into offering only Windows with Internet Explorer on PCs or risk losing access to Windows on their machines.

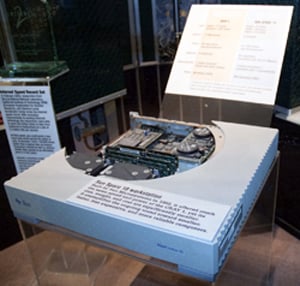

Faded glory: a Sun Sparc 10 as museum artifact

A hard-dealing Microsoft had told OEMs such as Dell how their PCs would look at boot-up, and to make sure Windows was not only prominently branded but was the only operating system offered. The OEMs complied — it just wasn't in their interests to sell or support Solaris anywhere and risk Microsoft's tearing up their Windows licensing agreement.

In 1998 McNealy testified in front of a US Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on whether Microsoft held a monopoly, just ahead of the DoJ's case. He appeared with Bill Gates. McNealy — a fiery capitalist from the Adam Smith school of economics — famously branded Microsoft a monopolist whose control of Windows was killing innovation.

"The only technology I'd rather own than Windows would be English," McNealy told US politicians hearing his testimony. "All of those who use English would have to pay me a couple hundred dollars a year just for the right to speak English. And then I can charge you upgrades when I add new alphabet characters like 'n' and 't.' It would be a wonderful business."

Looking back, McNealy's feels like a Cassandra whose warnings went unheeded — with the fallout hitting his beloved Sun.

"I thought it would be better to let Dell try to sell it [Solaris on x86] but Dell was under strict orders from Intel and Microsoft not to deviate. I said it all back then, and now it's all come out in the court documents and that was hugely damaging to Sun, and they got a slap on the wrists," he said. "I feel good as a company we didn't engage in that. I sleep better at night — but not on a yacht!"

You can't just blame Dell for the failure of Solaris on x86 — Sun shares some of the blame. Remember that version of Solaris for x86? Well, for some reason those execs with whom McNealy had disagreed decided to stop the practice of making a version of Solaris for x86 with Solaris 9, and to just to make the operating system for Sun's Sparc servers instead. The company quickly reversed course following an outcry from loyal users. Solaris 9 for x86 shipped in January 2003, eight months after Solaris 9 for Sparc. It was the first time since 1994 that Solaris on x86 had lagged the version destined for Sun's own servers.

History lessons

History might have been different had Sun open sourced Solaris sooner and delivered its own x86 servers rather than rely on a set of compromised Microsoft partners. It might also have been different had Sun ventured away from hardware sooner and into that other great moneyspinner, the database. Not having a database was Sun's "Achilles leg," McNealy said. "Oracle sucked an enormous amount of life blood out of [Sun] customers because we didn't have a database to compete."

Oh irony, where is thy sting?

Had Sun transitioned sooner to x86 and a more measured form of open source that you could make money on — not the insane sprint it became towards the end of Sun's life — Sun might be alive today. It might be the kind of diversified tech company that Microsoft and Oracle are now.

A businessman in the hippie state of California, McNealy founded Sun on a belief you could make money from open systems — he fused BSD with workstations to scorch the opposition in the 1980s. In the end, it was the making money part of that equation that escaped Sun.

Sun made $200bn during the course of its lifetime doing what it did best: building and selling powerful workstations and servers built on an open core, not by open sourcing its software and hoping for the best. McNealy and Sun made their billions without resorting to the kinds of abusive tactics Microsoft used or becoming infected by Oracle's zero-sum, almighty-dollar competitive ethos.

With that thought in mind, I question just how much McNealy really honors Ellison when he bats around "good" and "great" capitalist. McNealy's a capitalist, sure — while he's never read Atlas Shrugged, McNealy cites its author Ayn Rand as his mentor while he was growing up. Rand is a hero to those on the political right and in business because of her philosophy of individualism, the free market, and personal responsibility.

Yet, McNealy comes across as old-school, fair-play, slightly paternal capitalist versus Ellison's cult of the dollar. McNealy's dad came from the blue-collar American economy — cars, where product was tangible and the rules of combat and competition clear — as a vice president of American Motor Corporation, eventually bought by Chrysler. That had to rub off.

Would McNealy use this experience and what he's learned at Sun to lead another tech company? Jobs are available: Nokia and HP, after all, recently had open CEO spots, while start-ups are always on the hunt for the kind of credibility that "grey eminence" talent lends them.

Don't count on it. "I'm asked daily to be on boards and be CEO, but I'm doing all my little free stuff. I like free right now because I can continue to say what I want to say."

Again with the "free". ®