This article is more than 1 year old

Lower termination rates will bring pricey data

Good for telcos or punters?

Ofcom has proposed a steep decline for termination rates, hitting a ha'penny a minute by 2014, but can a measure that saves consumers £800m a year be all good news?

Not according to Orange, which reckons the change will stifle innovation, stall investment and lead to customers having to pay to receive phone calls. This contrasts with 3UK, which tells us the news will lead to lower prices, better deals and (quite probably) dogs and cats living together in peace and harmony. So is a lower termination rate good news or not?

The termination rate is the fee paid to the recipient network - a cut of what the caller pays, set by the regulator and intended to cover the cost of routing the call over the cellular network.

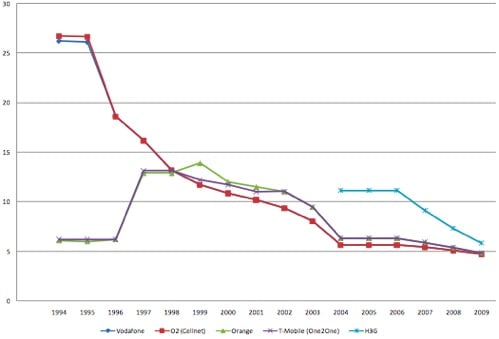

That sounds simple enough, but working out the cost of routing isn't as easy as it sounds. Historically the rate has also been skewed towards later entrants to help them gain a foothold, making it much more complicated.

Termination rates in pence per minute

The process is further complicated by customers who change networks. When that happens the original network collects the termination rate and forwards incoming calls, but the rate it collects is its own rather than the rate of the eventual recipient network. This hurts smaller networks (such as 3) which might have got a better rate if the call had been connected directly.

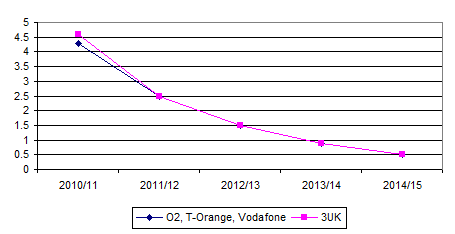

That disparity and complexity should disappear over the next few years, if Ofcom's proposed downward slide is approved:

Future rates as proposed by Ofcom

One might imagine that, given a level playing field, it would be a simple matter to calculate the cost of carrying a call, but unfortunately the field remains far from level. Operators paid different amounts for their 2G spectrum, for example, and have long argued that the rate should be based on what they paid for their 3G frequencies, as opposed to the (much lower) current valuation. Lower frequencies require less density of base stations, which should result in lower running costs, but that would make things way too complicated, so a single average figure is used.

But if the rate is set too low some customers can cease to be worth anything at all. In 2008 Vodafone claimed that 40 million of its European customers would simply be uneconomical to keep without a decent termination rate. This is particularly harsh as those customers tend to be the poorer demographics.

Orange reckons that lowering the termination rate will hit subsidised handsets and network investment - why build a 4G network when you can't charge a premium for calls carried over it? Ofcom claims the cuts will save consumers £800m a year, and 3 has now promised to cut prices "significantly over the next two years", but 3 isn't planning to build a 4G network any time soon, so it can afford to make that kind of commitment.

Our 3G networks were built on the basis of predicted income, money effectively borrowed from future customers - which would be us. Borrowing from the future was all the rage a decade ago, but with our children now pretty much bankrupt there's no one to pay for 4G networks except ourselves.

Without the income from termination rates the mobile operators will need to be more transparent about where their revenue comes from - so we'll see a greater push towards tiered pricing for data. Overall we'll probably end up spending a little less on our mobile telecommunications, at a cost of delaying the deployment of next-generation networks. Whether you think that is a good thing remains a matter of opinion. ®