Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2014/11/02/whatever_happened_to_photography/

Snapper's decisions: Whatever happened to real photography?

Automatic for the People

Posted in Personal Tech, 2nd November 2014 08:01 GMT

Feature Gradually and quietly, there has been a revolution in photography which has seen traditional film eclipsed by digital techniques. John Watkinson argues that the results of the revolution are not all beneficial, not least because the evolutionary path from amateur to professional has been economically closed off by marketing.

Design classic: the Hasselblad 503CW marked the end of an era in 2013 for its V System film cameras

For me the revolution is over. I’m a committed medium format digital photographer. I haven’t shot any film in years and there is no way back for me. One of the attractions of photography is that, like the helicopter, it is multi-disciplinary and provides a meaningful intellectual challenge; the satisfaction of learning a skill.

The technical performance of the equipment must remain within limits that are set by physics, whereas the actual results may fall far short of those limits if the photographer doesn’t understand the principles.

A technically flawless photograph may be unappealing because of the subject matter or the composition. There are interesting phenomena such as colorimetry and body mass distortion that have both scientific and psychological aspects. Another interesting aspect of the photographic revolution is that marketing now has such tight control that you can’t actually buy what you need any more, so you have to make it yourself.

Human vision is stereoscopic and obtains some depth clues through disparities between the two images, whereas most cameras have a single lens, like the mythical Cyclops, that loses the disparity depth clues. Seen with two eyes, objects obscure less of their background and that’s what we are used to.

Seen through a camera with one eye, objects look wider. That’s great for the guys, who are perceived as more muscular. Not so much fun for the girls who are perceived as fatter and flat-chested, hence the Hollywood starvation and silicone syndrome and the reason most women hate having their picture taken.

Profile pics: the Baywatch babes know how to strike pose... well, two of them know the trick

Source: GTG Entertainment

So if you remember one thing from this article, it’s not to take pictures of women through telephoto lenses which make the effect worse. And girls, if someone pulls a camera on you, don’t stand square on to it like a rabbit in headlights. Take precise aim at the camera with one breast, so the other one will be in silhouette.

Any new technology is automatically reviled out of a combination of vested interests, fear and ignorance. I remember the introduction of digital audio and how professionals, consumers and journalists alike often showed they had no clue about the basic principles. Most of what was printed was only suitable to put under the cat’s dishes. The consumer music industry would subsequently be destroyed by IT.

Move on a few years and we see the same thing in photography. Misinformed Luddite professionals believe that experience is an alternative to an understanding of new technology. Confused consumers suffer journalistic guano and a tsunami of marketing that may drown us all in a last ditch attempt to stave off destruction by IT. My most important photographic accessory is a bullshit filter.

Dynamic change

Inevitably there are pros and cons but let’s focus on the positives for a moment. As will be explained here, the resolution of a good digital camera is limited by the lens not the sensor. The colorimetry is more accurate and more stable than film and the dynamic range is greater. Fig. 1 shown here was taken in Sweden with a 12 stop digital back and shows full sun on snow outside the windows; yet indoor details are also visible. That picture could not be taken as a single exposure with film.

Fig.1. This scene has too much dynamic range for film and the eye but not for a 12 stop digital sensor. Note that the DR has had to be reduced to allow the eye to take in the whole scene

A great advantage of a high dynamic range camera is that if a shot is under-exposed, it can be dug out of the dark in post production without obvious noise build up. Over exposure causes clipping and there is no solution, so if in doubt with a digital camera, go for under exposure.

But the advantages of digital photography go way beyond the technical quality. The primary advantage is the near immediacy with which the captured image can be assessed so that if anything is not right another shot can be taken. This is not such a big deal for holiday snaps, but when using fill-in flash, perspective control lenses, filters, or in macro-photography it allows a better result to be obtained sooner.

With film you have to wait for it to be developed before you can find out what you did wrong, by which time you have forgotten what you did unless you wrote it all down. Many digital cameras can display histograms of the captured image so a rapid confirmation of correct exposure can be made. The ability to zoom in to a small area of the captured image allows a check that what should be in focus actually is, and equally importantly, what should not be in focus isn’t.

Fig 2 (left) Ross Errily Friary shot in the rain, the cloud cover has changed the colour temperature and the stone is almost monochrome. Fig 3 (right) colour correction brings out the hue of the stone – click for a larger image

For a long time I shot 35mm transparencies, and the photography was essentially complete when the shutter fired. I was always disappointed with the colorimetry when the sky was overcast and everything came out looking cold. In principle I could have used filters on the camera, but how many would I need, and how would I assess which one to use? I might have taken years to learn how to do it.

With a digital camera I can change the effective colour temperature of the illumination a few degrees at a time either in the camera or in post production and obtain balanced shots when the ambient light is off the standard white point. I learned how to do it in minutes. Fig.2 shows a near-monochrome shot taken in rain, whereas Fig.3 shows the colour corrected result. Fig. 4 shows a colour problem due to artificial light, whereas this has been white-balanced in Fig.5.

In addition to having many advantages, there is also a down side to digital photography. Clearly a digital camera contains some computing power and that can be used not just to transfer the image data to the memory device, but for various other purposes. These include automatic exposure and automatic focus. Whilst one argument is that these features make the camera easier to use, the other side of that argument is that if no skill is required, no skill will be learned.

Fig.4 (left) Tommy O’Sullivan’s pub in Dingle is the best live music spot for miles. Artificial light with a very low colour temperature make the camera think it’s green. Fig 5 (right) after colour correction, showing that the pub is actually blue. Note the license plate on the car is now white – click for a larger image

Traditionally, the still camera market was divided into viewfinder cameras and SLRs. In the former there is an optical system that is held to the eye for framing purposes that is quite separate from the main lens. The framing accuracy of these cameras was never good.

In contrast, the SLR (single lens reflex) camera intercepted the light from the main lens with a mirror so the viewfinder showed what the film would see, allowing the use of interchangeable lenses. The mirror would swing out of the way before the actual exposure. Viewfinder cameras were small and light and appealed to the mass market, whereas SLRs were heavier and appealed to the enthusiast and the poseur.

Zoom trends

Digital cameras initially copied the viewfinder or SLR model, and later so-called bridge cameras were available in which the optical viewfinder was replaced with a live view on a screen and mirror-less cameras having electronic viewfinders. However, due to the economics of silicon manufacture and yield, digital cameras mostly have sensors that are smaller, sometimes a great deal smaller, than the 24 x 36 frame of 35mm. Thus for the same field of view the focal length of the lens would have to be reduced.

Unfortunately, optical systems do not scale because the wavelength of light has to remain within the range visible to the human eye and so the energy of photons doesn’t change. If a lens with no tolerances or manufacturing defects could be made, it still could not focus to a point because of diffraction limiting that causes point spread that gets worse as the aperture is reduced.

There is no point in engineering a lens that is fantastic at full aperture and deteriorates as it is stopped down, so a good lens will have approximately balanced point spread due to aberrations at full aperture and diffraction at minimum aperture. The best performance will be somewhere in the mid range.

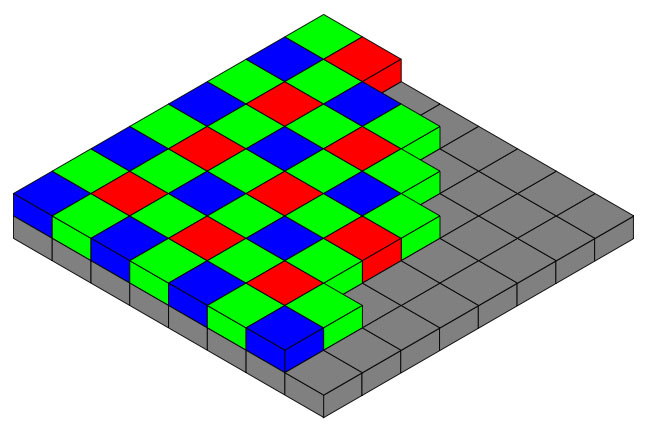

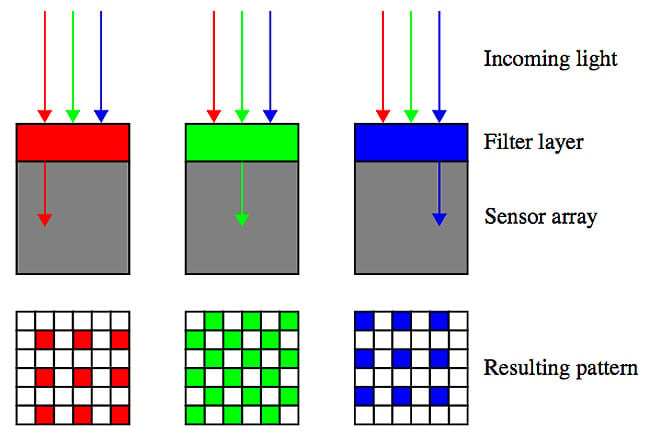

Bayer sensor filter pattern – source: Wikimedia, Cburnett, Creative Commons

One immediate consequence is that the number of pixels output by a camera has no direct bearing on how sharp the pictures will be, even though pixel count features heavily in the specification. The first point to bear in mind is that digital camera sensors don’t have pixels; they have photosites. Most single chip cameras capture colour images by having a Bayer pattern of three different colour filters distributed over the photosites, so that some capture red, some green and some blue.

As the eye is most sensitive to green there will usually be as many green photosites as red and blue together. The raw data file that is typically recorded in the camera memory is the photosite data and needs, inter alia, de-mosaicing to compute pixels that produce a digital image. Typically four photosites are needed to create one pixel.

There’s no point in having enormous pixel counts on a small sensor, because once the resolution limit of the lens is reached, increasing the pixel count is futile. A four-thirds format digital camera is unlikely to deliver more than four megapixels of information per frame, irrespective of how much data it outputs. Pixel count is to cameras what sampling rate is to Pono: both allow marketing to quote a bigger number to the gullible.

Bayer pattern on sensor profile. Photo via Wikimedia, Cburnett, Creative Commons

Another great leap backwards for photography was the proliferation of zoom lenses on consumer digital cameras. A glance at the optics of a good wide angle lens and a good telephoto lens will reveal that the bits of glass are somewhat different. Trying to be both at once is going to be a compromise that will result in loss of aperture and loss of resolution. But that’s not the worst problem.

The problem is that the unskilled user simply stands where he is and zooms in to fill the frame with the object of interest and ends up with an image that is as flat as a cow pat and completely lacking in perspective. The photographer gets off his butt, trudges closer with a fixed wider lens, spends an age selecting a viewpoint and comes back with a photograph. As Ansel Adams said: “A good photograph is knowing where to stand”.

As photons don’t scale, smaller photosites just get noisier, which is why cameras in iPhones croak in the dark. There is such a thing as an ideal size for a photosite, which is where four of them more or less fit in the point spread function of the lens so sensor and lens match. The number of pixels then depends on how big the sensor is. As sensors go, big is beautiful and Moore’s Law is irrelevant. Big sensors offer the best resolution and the lowest noise which translates into high dynamic range.

In the frame

Figs.6 and 7 show pictures that can be blown up to about two metres across before they go soft. These images are only 22 Megapixels, but they are not marketing pixels, and the images have come though a properly engineered lens, so they are rich in information. Fig. 8 shows a time exposure in which noise is not an issue.

For the full resolution version of the images below, click click here (27MB).

Fig.6. La Chapelle de Walcourt not long after almost a million Euro was spent on a stunning restoration. This was taken with only 22 Megapixels, but because the sensor is huge the pixel count means something. A shift lens (Sekor 50mm) was used to get the perspective correct and as the sun was merciless a polarising filter was used to take some of the glare away. A blond beer was needed to cool the photographer

Cameras with small sensors tend to have larger depth of field making it harder to use selective focusing to lead the viewer’s eye to the subject of interest. It is difficult to be specific because small sensors have physically smaller lenses that may be economic to make with larger apertures, ameliorating the problem somewhat. Nevertheless, subjectively small sensor cameras do seem to produce images in which everything is in focus. So you never know if their bokeh is OK.

Early mass-market cameras such as the famous Kodak Brownie used 120 film, which was 70mm wide but had no sprocket holes, so most of the film area could be used. As film resolution and lens quality increased, the film width was halved to use 35mm film whose dimensions were identical to cinema film.

However, cinema film ran vertically and each frame was four perforations high. In still cameras, the film ran horizontally so the frame was significantly larger at 8 perforations wide (24 x 36mm). Whilst cinema film must have sprocket holes, they are not necessary in still photography. Without holes, a 35mm film frame could have been 30 x 45mm, but the opportunity was lost.

Fig.7. The town hall in Heybes on the Meuse. Another shift lens and polariser shot. Another beer.

120 film then continued in use in medium format cameras aimed at the professional market such as the Hasselblad, Mamiya and Bronica, which were so called because the image size was larger than that of 35mm but smaller than that of plate cameras. Image sizes of 60 x 45, 60 x 60 and 70 x 60 were popular. These medium format system cameras in many ways defined the golden age of photography by being able to photograph practically anything with startling quality.

Hasselblad and Zeiss, who made their lenses, had a prolonged performance war with Mamiya to the benefit of all. Back then, I had pushed 35mm as far as it would go and was tempted by medium format, but for various reasons and diversions there would be a delay before I got there.

In order to make the viewfinder work, 35mm SLRs universally had focal plane shutters consisting of two curtains immediately in front of the film. The first curtain would travel across the frame, admitting light, then the second would travel, shutting the light off. At fast shutter speeds, the second curtain would set off before the first had completed its journey, meaning that a moving slit of light traversed the film. That was fine for naturally illuminated shots, but no good for flash where the light is instantaneous. For fill-in flash – that softens shadows in daylight – it might be necessary to use the flash along with a short shutter time.

Fig.8 Time exposure taken in Bruges showing freedom from noise that characterises large sensors. Thick socks were worn for this shot

Medium format cameras got around it by putting shutters in the lens. In the classic Hasselblad, there is a pair of barn doors behind the mirror that normally cover up the film. In order that the viewfinder can work, the shutter in the lens must be open. When the exposure sequence is triggered, the lens shutter closes, the mirror goes up and the barn doors open. The lens shutter then opens for the selected time to expose the film and then closes. The barn doors close, the mirror descends and the lens shutter opens again. All lenses used with the Hasselblad must contain shutters.

Mamiya went a stage further by having a focal plane shutter for use with non-shuttered lenses as well as allowing shuttered lenses to be used, when the focal plane shutter simply opens for longer so the exposure is determined by the shutter in the lens. Mamiya’s motor wind would advance the film and wind up the focal plane shutter. The shutter lenses are electric and are connected to the motor wind by a short cable so that it can wind up the lens shutter as well.

Get your own back

One of the great boons of medium format is the interchangeable viewfinder. The pentaprism viewfinder that allows viewing along the lens axis can be replaced with a waist level finder that allows viewing from above. I much prefer waist level finders as they save weight and allow better composition. They seem to make the edges of the frame more tangible so the viewfinder is more like looking at a picture.

The bare essentials: lens, body and back as seen on the first Hasselblad used in space (modified 500c V System) during the Mercury-Atlas 9 mission is up for auction on 13th November 2014

Medium format system cameras also have interchangeable backs, so you can switch between monochrome, colour and Polaroid film in seconds. In due course, you would switch to a digital sensor and leave it there.

The small chip DSLR made a fair attempt at replacing the 35mm SLR, but the manufacturers of these things were so busy competing with each other that they failed to see the real threat, which was the iPhone. Even though silicon processes had advanced beyond the point where 24 x 36 sensors were viable, small sensors were retained because manufacturers had got themselves into a price war.

Every conceivable feature was added except resolution, making them an easier target for IT devices. At first the iPhone cameras were a source of amusement, but it was inevitable they would get better, such that there’s now little point in owning a compact point-and-shoot camera as well these days. Needless to say, cameras on other mobile phone platforms have excelled too.

DSLRs were sold on the premise that buyers would get better pictures. Unfortunately it’s not so. To get better pictures requires some knowledge of photography, which you don’t get by buying a DSLR, any more than buying a sports bag makes you an athlete.

Give an artist a recent phone camera and you will get better photographs than Mr. Average gets with a DSLR. I hate to think how many disappointed owners have DSLRs in cupboards. Sales of DSLRs and compact cameras alike are plummeting like a streamlined piano. They show the same curve as the demise of the vinyl disc and VHS tape, suggesting that it’s not a blip but a permanent change.

Medium format camera makers are already collapsing, so we are down to Mamiya and Hasselblad, both of which have been bought. Mamiya’s latest camera has a heavy fixed pentaprism viewfinder and the heavy motor wind is non-removable. These are colossal marketing drop-offs for a system camera and a big step backwards from the 645 Pro.

Mamiya 645DF+ with Leaf Credo back – note the fixed viewfinder

Moreover, the interchangeable back fitting was deliberately made incompatible with earlier models, so you can’t put the digital back on an earlier camera and continue to use your old medium format kit. That’s the same planned obsolescence that turned Detroit into a ghost town when consumers decided they didn’t want a new car every year.

Medium format pixel counts continue to rise to pointless numbers, with the unsurprising result that noise becomes a problem. Don’t worry, you can get noise reduction software that reduces the noise, and the resolution, again. Hasselblad actually sell a digital back that will fit on their old cameras, but the sensor size is about half the area of the original film frame and the images will be heavily cropped, so it’s not a real solution.

Touching the void

Digital photography today is another victim of the dead hand of marketing, where short term gain overrides any other concern. Broadly speaking, marketing has created two types of camera. There are those with small chips that are cheap – increasingly incorporated into a cell phone – have a rubbish lens, need no skill to operate and therefore teach the user nothing.

Ceiling Chapelle de Walcourt – click for a full resolution image (8MB)

And then there are those cameras with big chips that are so expensive that even professionals cringe. It’s like owning a jumbo jet: you can’t afford not to fly it, hence the constant references to workflow in the marketing. Alas, in between these two types we find the equivalent of a valence band or forbidden zone.

The traditional continuum of camera performance and cost that existed with film has gone, so there is no progression route for the keen photographer to climb. This is as bad as it gets. The small chip camera owner cannot cross the forbidden zone for economic reasons, and even if he did, he wouldn’t have the necessary skills. I think it is pertinent to ask where the next generation of professional photographers is going to come from. It’s an odd revolution that builds a safety barrier around the aristocracy.

My own foray into medium format digital used IT to its full extent. Following some online research I discovered that all digital backs have an external trigger socket so they can be used with movement cameras. It was then simple to obtain an old Mamiya 645 Pro body on eBay and to hack it to provide a trigger signal.

A small amount had to be milled away from the backplate of the camera to get the sensor plane to line up with the old film plane, and a small plate was needed to couple the items mechanically. So now I have a modern Leaf digital back on a 20 year old system camera.

Fig. 9. Twenty-year-old Mamiya 645 Pro with Leaf Aptus II 22MP back. Note 50mm Sekor shift lens, waist level viewfinder, spirit level and electric cable release

The lenses were world class then and they still are, as the images here illustrate. Unlike today’s offering from Mamiya, if I want to wander off I can save a lot of weight by replacing the heavy pentaprism with the waist level finder and replacing the motor wind with a simple hand operated knob. The great beauty of the camera is that it has no automatic functions whatsoever. I don’t want them and I don’t miss them. My photography is contemplative. It takes time to find the right viewpoint and to get perspective and filtering correct.

High resolution shooting is unforgiving of camera movement and most shots are from a tripod, which also helps composition. The extra time needed to focus, choose shutter speed and aperture is negligible. Technically the camera is so good I don’t have to waste time worrying about it. The limiting factors are the atmosphere and me – mostly me. ®