Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2014/08/24/wikipedia_monkey_selfie_backfire/

Cracking copyright law: How a simian selfie stunt could make a monkey out of Wikipedia

Creativity can't start and end at the push of a button

Posted in Legal, 24th August 2014 10:28 GMT

Analysis That so-called Macaca nigra monkey selfie isn’t in the public domain, no matter what Wikipedia wants you to think. In fact, the encyclopedia's stance on the matter could backfire and hit it in the pocket.

A photo sold by British snapper David Slater since 2011 hit the headlines again this month when Wikipedia refused to acknowledge Slater's claim that he owned the pic's rights.

Nobody had challenged Slater's ownership until now, but because a monkey pressed the shutter button and snapped the photo, Wikipedia reckons Slater has no claim of ownership.

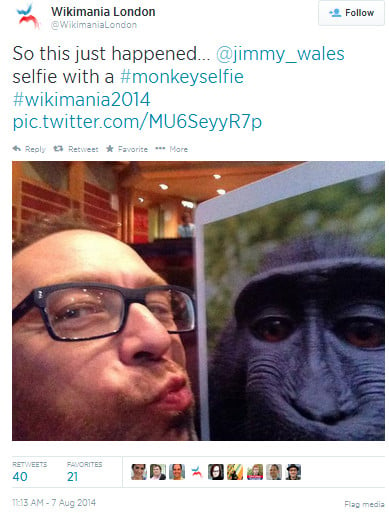

This interpretation of the law coincided with Wikipedia’s annual gathering, Wikimania – the website has a long history of grandstanding on digital property rights. The prank was popular with attendees.

Funny guy: Wikipedia supremo Jimmy Wales (left) takes the piss

Slater has been obliged to hire legal help costing thousands of pounds to defend his work, arguing that Wikipedia’s continuing publication harms his livelihood.

The law isn’t hard to understand.

Unlike trademarks, which have to be registered to get protection, copyright is an automatic right. As the creator, you’re the owner. The Berne Convention – which the UK, US and many others have signed up to – enshrines this. You don’t even have to include a © squiggle. It's automatic.

The question is whether Slater fulfills the necessary criteria required to be protected by the law as the creator of the Macaca nigra snap. Serena Tierney, who heads the Intellectual Property practice at London law firm BDB, explains how it looks in the UK.

"An amount of intellectual input is required to be the owner," she said.

"This was considered in a 2012 case, referred to the Red Bus case – actually Temple Island Collections Ltd v New English Teas 2012. It involved two largely black and white photographs of Westminster Bridge with a red bus crossing it.

"The judge had to consider whether the first photograph was protected by copyright in order to decide whether or not it was infringed. He considered three aspects that are relevant to establishing whether the photograph was the author's original intellectual creation."

These aspects are:

(i) specialities of angle of shot, light and shade, exposure and effects achieved with filters, developing techniques and so on; (ii) the creation of the scene to be photographed; (iii) being in the right place at the right time.

Slater doesn’t fulfill every single criterion – but then he doesn’t have to. He has to meet enough. As Tierney explains:

"If he checked the angle of the shot, set up the equipment to produce a picture with specific light and shade effects, set the exposure or used filters or other special settings, light and that everything required is in the shot, and all the monkey contributed was to press the button, then he would seem to have a passable claim that copyright subsists in the photo in the UK and that he is the author and so first owner,” she says.

“If Mr Slater is not the author, there is probably no UK copyright in the photo since it seems unlikely that a monkey could demonstrate that it had met the requirement that the intellectual creation be that of the author. This appears to be Wikimedia’s line.”

Whether you're on Team Slater or Team Jimbo, it's going to court

So what’s all this fuss about the US Copyright Office, then? This week it refused to register the copyright of monkey selfies.

One of the American quango’s statutory duties is to act as a deposit library, and to fulfill this, it needs to identify an owner. This has caused some confusion. But two things must be kept in mind: under Berne, copyright is automatic, and doesn't require registration. And secondly, disputes are settled in court.

Like the UK Intellectual Property Office, the US Copyright Office cannot settle private disputes. Hence why Slater must make an infringement claim against Wikipedia for using the pic on its website.

In a new draft of its copyright law compendium, published this week and set to be made official this year, the Copyright Office said it wouldn’t assign ownership in its catalog to spirits and animals, and it wouldn’t register machine-generated works. So the monkey, as in the UK, is out of luck.

But in terms of Slater’s claims, that’s neither here nor there. The US law has similar criteria to the UK. Some intellectual input is required in terms of composition – but not so much. Only a “modicum of creativity” is required for the human to gain copyright protection. Slater made choices such as choosing the location, the equipment, where it was placed – in front of the monkeys – and choosing what to keep and discard.

Even before the USCO update this week, it’s doubtful how any ownership arguments on behalf of the monkey could have been advanced. Did it see and recognize the camera? Did it know what a camera was? Did it exert its own intentionality – did it think: “That’s handy. I fancy taking a picture right now.” Did it know how to operate it? No to all.

Someone's not happy with Wikipedia's selfie decision

Declaring the image public domain could backfire badly on Wikipedia; it looks mean-spirited by suggesting creativity starts when a button is pressed and ends when it's let go – something so mechanical, a monkey can do it. Who needs artists, anyway? This is a deeply misanthropic argument, but one which some Wikipedians seem to be reveling in making.

As veteran Wikipedia contributor Andreas Kolbe reported:

“The Wikimedia Foundation has turned [the monkey selfie] into a symbol of its determination to retain content on Wikimedia servers ... it had also been used as a sort of conference mascot, with prints of the image displayed in numerous places around [London's] Barbican conference space.

“Even at the registration desk there was a copy of it, inviting attendees to take a selfie of themselves next to the image. As followers of the Wikimania Twitter stream could observe, Jimmy Wales led by example – and was rightly called out by some users on Twitter and, indeed, Wikipedia, for what appeared like tactless gloating."

The power relationship seems clear: using the image cost Wikipedians nothing, but an individual may have to dip into his savings to protect his livelihood.

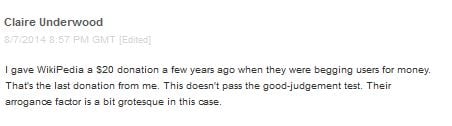

Perhaps the threat of withholding donations may make Wikipedians reconsider their actions.

Would you fight a 30-million-pound gorilla?

Berne, which enshrined copyright as a right for the individual, is as relevant today as it was then. It was devised to protect creators from unscrupulous publishers who wanted to use and none want to pay.

The simian photo prank strongly gives the impression that Wikipedia has chosen which side it’s on: it’s against the little guy, it’s against the creator, and it’s got a $50m war chest to bankroll any legal battles. It has the riches an individual can’t muster.

Slater says he made a mere £2,000 in licensing the image – which, we're told, only just covered his travel expenses to Indonesia to obtain the photo. By putting the image on one of the most popular websites in the world, Wikipedia has endangered his chance of making any more cash from a world-famous photo.

It's a pity the UK's mooted small claims court for intellectual property has not advanced. This would allow individuals like Slater, without a wealthy foundation backing them, to get speedy justice and damages at a low cost.

Amateur Photographer reports that German company Picanova is offering a canvas print of the famous photo for free – it makes a little on postage – with permission from Slater, and it will donate a quid per copy to a conservation charity. Just something to consider if you're still thinking about donating to Wikipedia. ®