Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2014/05/09/net_neutrality_explained_and_how_to_get_a_better_internet/

WTF is Net Neutrality, anyway? And how can we make everything better?

Ignore those beardies - here are the facts

Posted in Legal, 9th May 2014 15:29 GMT

Special Report This weekend, earnest young men - several of whom appear to have beards - are camping out in Washington DC. They're protesting against "plans to allow a pay-for play internet".

In fact, we think there genuinely are some serious competitive concerns about recent developments in the ever-changing business of carrying bits of data - they're just not the ones you (and the beards) might think. Talking about "net neutrality" raises fascinating questions - but they are far from simple. We think you might like to know what these are.

So we're bringing you a bullshit-free guide to what to what's really happening here - and what you may want to worry about, so you can better direct your energies.

This is strictly non-ideological. There will be no principled arguments for "the public good" or the sanctity of non-intervention. The internet has to work - and work well, well enough to serve everyone - not just the people who shout the loudest, or who lobby well. Today, some groups (such as the disabled) are very poorly served, as we shall see. The internet also has to grow and develop in ways we can't anticipate today, which is still the Jurassic era of networking. If you want to freeze things as they are today - or put another way, if you think it's as good as it gets today, then please stop reading. Here instead is a ten hour video of some unicorns on rainbows - or you may prefer a long train journey).

The well-funded Net Neutrality campaign in the US is strongly backed (and funded) by internet content and services companies. These campaigners make an emotively powerful argument: that without intervention, we will see a "two speed" internet, with new payments forced upon people who are obliged to use a "fast lane". Net neutrality proponents say that internet packets should be treated equally, or at least "fairly". This is typically backed by the a claim that "it's always been this way".

Preferential speeds, data discrimination - the campaigners argue - are both new and bad.

Let's try and measure this against reality.

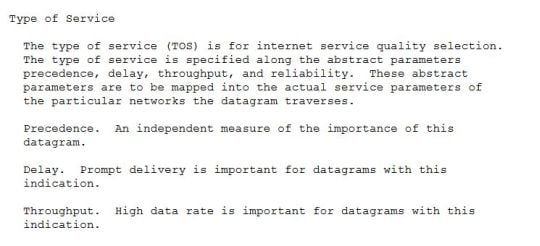

Giving a TOS

Exhibit A is a portion of a historically important document that's more than thirty years old. It's RFC 791 and it was written in September 1981. The whole document specified how packet networks would talk to each other. That's what "internetworking" was, and is - networks agreeing to talk. No wonder it's known as the "mother of all internet protocols" - every significant protocol refers to this, and it described the IP packets you're using today to read this. The portion below describes the header of an IP packet, the DNA of the internet.

Now have a look at what we find.

The IP header reserves bits for what kind of packet, the "terms of service". In other words, right from the start, the internet was designed as a multiservice, or "poly service" network. Packets were never "equal" - they could and would have to go at different speeds. The TOS headers have never been implemented, the job of shunting things through at different speeds being inferred from the traffic flows rather than interpreted from the data itself. But TOS shows what the original thinking behind the internet was.

Give it a moment's thought and you'll see that it can't really work any other way: some things like real-time video require very low latency and low jitter, other things can wait a few milliseconds longer.

"Regulators aren’t helped by the legal and academic classes clinging to a fantasy that FIFO queues represent some kind of ‘neutral’ mechanism, and that all packets were created equal in some kind of Rawlsian system of information justice," writes Martin Geddes, whom we'll hear more from later.

In other words, we're projecting a utopian political concept into a place it doesn't belong. We could benefit from looking at this in a more hard-headed, practical, technical way.

But wait, you're thinking - don't we all believe in fairness?

And "slow lane" discrimination against a smaller, less profitable business isn't fair - right? Exactly so. Let's now look at the reality behind this claim.

The ever-changing road

Once again we need to look at the internet while remaining rooted in reality. I'll illustrate this by practical analogy.

Imagine you're a new, startup internet video company. You may have acquired a world exclusive for distributing, say, Breaking Bad, which nobody has yet seen. Or you may just have unique and brilliant videos you want people to see via the web. It doesn't really matter - and nor for the sake of argument does your "business model" matter here: you simply need to serve video, and serve it without delays. If you can't do that people will abandon you, they won't watch - and you're stuffed.

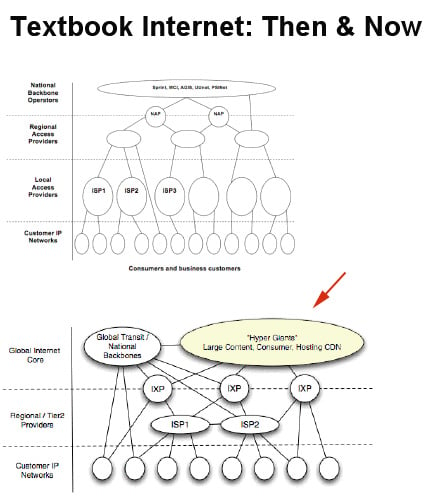

Behold the "Hyper-Giants" ... The internet looks different now Source: Atlas IO Report 2009

As the Neutrality protestors describe it, today you enter the "highway" on a slip road and your video floods over to the punter without you paying any tolls. Actually, that's a problem, the phrase "pay to play". You do have to buy bandwidth between your own network and the wider internet, which is not free. What the neutralists fear is that you have to pay twice, or an additional toll because a gatekeeper has interceded on the formerly free'n'open highway, positioning themselves downstream between the wider internet and the viewer, demanding a new fee.

And that's our second major problem. Fifteen years ago this is how "content" was delivered, with most content back then being web pages which were mostly text. It's how The Register and thousands of other sites got started. Fifteen years ago you merely bought bandwidth once - access to the public backbone - and the packets you wanted to deliver traversed along those public backbones and thus to the user.

But it's not how streaming video is delivered, now, today. It's not how streaming video has ever been delivered, in fact. Today, those backbones are dilapidated and weed-infested dirt tracks. No video provider uses them - or would even dream of using them. They can't carry video. With the benefit of hindsight we may rue not requiring large telcos (perhaps paid a tiny fee or tax) to maintain those public backbones - a kind of Universal Service Fund - to keep them in good nick. But hindsight is a wonderful thing.

Instead, video providers use - are forced to use, due to their performance requirements - private networks. This is where the great Darwinian advantage of the internet has paid off somewhat. TCP/IP was crude, but its crudeness and flexibility helped it grow. The internet protocols are merely a bare minimum set of instructions on how networks should interconnect - not what goes on inside them. So the fact you can now watch a ten hour video of unicorns dancing on rainbows is because providers can get the data to you across a fast private network.

(As an aside, almost two thirds of traffic measured by volume still uses the weed-infested public backbone, but it's almost entirely Bittorrent traffic and cyberlockers. People using Torrents and lockers tend to have lower quality demands than Netflix subscribers. It's free and the material is dodgy - I'm not going to sue the shopkeeper I'm robbing, the freetards reason, for making the sweets hard to reach. The rest of the public-network traffic is stuff that doens't need to get through fast, like email. )

And what kept things largely civil to date was that the various network players - ISPs and private delivery networks - tended to exchange roughly equal, or symmetrical, amounts of traffic.

What's changed?

In short, you as a video provider will hire a delivery network (or build your own - we'll come to that) to talk to your eventual customer's network (an ISP), faster than would normally be possible without the specialist delivery player. So to do video, you must hire a "fast lane", or build your own. Thus peering becomes important. It becomes highly political. Now we're getting to the core of the issues in play with Net Neutrality - but we can do so without being prisoned by our metaphors.

"The road metaphor breaks down because the road is constantly changing," is how Paul Sanders describes it. Sanders is both an ISP and a service provider who writes thoughtfully about competitive issues. And he's written for us - mostly about the failings of the music biz.

Another popular metaphor falls apart too, once exposed to the harsh daylight of reality. A network is a limited resource, with people always fighting for it.

"It is always contested even when it is not congested," notes Sanders.

Here ISPs face an uneviable dilemma. Many of the problems today would not be problems if the internet's design had been a bit less crude. Congestion control was discarded early on. Yet congestion remains a critical issue.

"The utopian view of network is everyone plays nicely. But other internet users are not neutral to you. Every packet is pollution to someone else and the polluter doesn't pay. So really it's a war, a battle for resources, in which the greediest application over the biggest pipe triumphs. The strongest will always win," is how Geddes describes today's internet.

As I said in the introduction, there are genuine competition implications - how could there not be? - when big bucks are at stake. What's happened this year, in a nutshell, goes like this.

Going to war for um, capitalism

Let's return to you as video provider. Netflix - as you too would hope to - grew and grew. It bought access to a private network, Cogent, to deliver its streams to its customers' ISPs quickly, and it also used caching inside ISPs to store its most popular shows. That latter relieved Cogent of some of the traffic load, and saved Netflix a bit of dosh.

Others have taken different routes. Google operates the world's biggest private network, and it had to build it so that it could deliver YouTube's video. Nobody else can use Google's road.

Netflix found as it grew that congestion at Comcast - the massive US ISP - was causing it problems. So it did a fairly sensible thing. It dropped Cogent and peered with Comcast directly. This actually saved it money. It's a popular myth - propagated by staggeringly bad reporting - that Netflix now "pays twice". Er, no: it pays Comcast directly, and it pays less than it used to. Net neutrality campaigners portray this as Comcast "demanding a ransom", or a kind of extortion. That isn't actually the case.

The Neutralists fear that every "over the top" content provider will have to pay not just to get the video to the ISP, but will also have to pay the ISP to carry the packets the "last mile" into people's homes. A popular graphic campaigners like to exchange shows an ISP demanding fees from Twitter and eBay, and passing them on to the end user. The sky is falling!

Well, let's see.

For a start, eBay and Twitter don't need a 'fast lane', they don't need to hire a CDN. They use very little bandwidth compared to even a modest streaming media provider. They don't generate asymmetrical data flows between networks. And even if they did need a fast lane, their choice of providers is quite broad. There are many networks to choose from.

"Ideally, a smart content company would have several different competing CDN type operations to choose from – and they'd choose the lowest cost routing," explains Sanders. "But what they should be worrying about long-term is the fact that almost none of the traffic these days is going over what you might call 'the internet'."

And here the real competitive concerns about the direct deals are plausible. Sanders sums it up:

"The buyer (a Netflix or Google) achieves a far greater efficiency of content delivery, and is able to compete better for the contended, congested bandwith on the consumer network, which effectively squeezes out competitive video from the internet."

"The dark side of this is that by choosing which route to direct traffic into a network, a large content provider can coerce consumer ISPs into co-locational private peering, by deciding which route their content takes. This only happens when the flow is hugely asymmetric – when there's no peering of equals."

Have you got one of these, Mr. Beard? Thought not

And the result of that is that a Netflix or Google can squeeze you, dear video startup, out of the game.

This is the real competitive issue raised in the USA by the latest Netflix agreements, and it also explains why Google is such a spectral and ambivalent presence in neutrality debates. Google sponsors 150 front groups, many of whom campaign "for" regulation, to "Save The Internet" - but it's also keenly aware of how its own fast lanes give it a competitive advantage. It's got tens of thousands of servers at ISPs around the world. Not many plucky startups have that.

In other words, Netflix/Comcast is not "Big Old Media Video" bustling out "Plucky Internet Startup Video" - it's "Big New Over-the-Top Internet Video" ensuring it can muscle out "Small New Startup Internet Video". It's Netflix buying a competitive advantage.

Should gay packets be allowed to marry?

By now I hope you'll see that the map you have been given does not describe the territory you're living in. On the map - the map the Neutrality campaign presents to us - are things like highways, lit by things like "packet equality", and featuring "threats" (here be demons!) like "pay to play". But we can't use a faulty map to develop wise policy, particularly if this entails technical regulation.

It's hard to resist quoting Tom Lehrer when earnest bearded young men campaign to "Save The Internet" - particularly when they give us a misleading picture of how it actually works:

(Lehrer sang: "We are the Folk Song Army / Everyone of us cares / We all hate poverty, war, and injustice / Unlike the rest of you squares.")

It's certainly been true that scaling an internet business (like a Twitter or a Facebook) is cheaper and faster than scaling a physical business. Growing your corner shop to compete with Tesco and Asda nationally takes a huge amount of capital investment. But guess what? Scaling Twitter of Facebook costs money too. Twitter only got to an IPO after burning through hundreds of millions in VC capital. The utopian premise that you can rule the world with just a good idea always was a bit of a fib. But we want (I hope) a better internet - one where new ideas can flourish, rather than be crushed by incumbents (like Netflix) with deep pockets. What shall we do?

That's really scope for another article, but I'd suggest one or two things right away.

Many readers complain that the US access market is not competitive. Yet more people prefer to complain than switch providers. Some 89 per cent of Americans have a choice between at least two broadband companies - so why not switch? Why not throw a switching party for everyone on your street? Start acting like customers - it's the only thing that scares the hell out of an ISP.

Another useful ploy is to ensure that existing US anti-competition laws are enforced. In an area with a duopoly, collusion between a DSL and cable provider should be illegal. Are you sure they're not colluding? Really sure? There are competition authorities that love to examine this sort of thing - so make their day.

Further out, identify and support competitive services and technologies. The FCC drove local ISPs out of business by allowing the local Bells to retail at wholesale rates. Get this repealed. If you're a gamer, seek out an ISP that promises low latencies, for example. Encourage others to do so. Wireless technologies now look a better bet for rural coverage. Get agitating.

And finally - remember that large corporations will always want a free ride, or a leg up - and yes, sometimes internet companies do too. They're not afraid of telling lies or manufacturing myths to gain an advantage, particularly when there's a lot of public good will toward the internet "as it is today".

So don't be taken for a mug. ®