Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2014/02/14/monitor_micro_men/

Micro Men: The story of the syntax era

The making of a retro-tech telly classic

Posted in Personal Tech, 14th February 2014 09:02 GMT

Monitor is an occasional column written at the crossroads where the arts, popular culture and technology intersect. Here we look back at the BBC TV movie Micro Men, a retro-tech fan favourite which tells the story of the rivalry between former colleagues Sir Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry, and how the two men kickstarted the British home computer boom of the early 1980s.

The show that became Micro Men - its working title was the punning "Syntax Era" - was conceived in 2008 by Producer Andrea Cornwell. She had already produced a number of short drama films and documentaries, among them The Yellow House, Cheap Rate Gravity and D.I.Y. Hard, and was naturally enough thinking about what might make a good subject for her next project. One of the ideas she had been pondering - after plundering Wikipedia for inspiration, chuckles the show’s director, Saul Metzstein - was the story of the British home computer boom of the early 1980s.

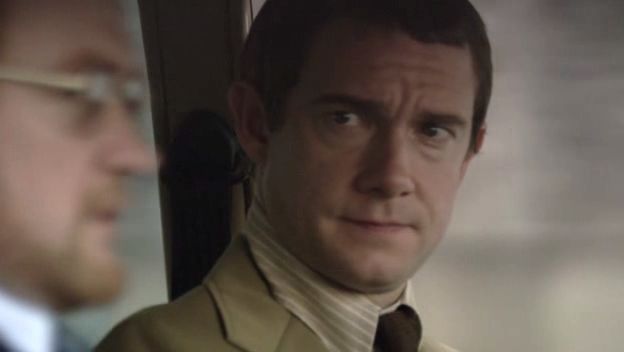

Clive Sinclair (Alexander Armstrong) and Chris Curry (Martin Freeman) ponder the future... down the pub

“I felt was a very interesting topic story which ultimately had a massive impact on all of us and how we interact with computers today,” Andrea tells The Register. “The human story behind the technology had an almost Shakespearean quality, and I really wanted to bring this to life in a nostalgic but also a fun way - to make it a celebration of the period.”

The saga of Sinclair Research’s head-to-head rivalry with Acorn Computers is central to the history of the British personal computer industry. But it’s not just a business and a technology story. Its momentum sprang from a very personal conflict between two former friends turned enemies – Acorn’s Chris Curry and Sinclair Research’s Sir Clive Sinclair – which added zest to the spats between two business opponents.

They competed with each other to bring the first and the best products to market, then to win the favour of the BBC, which wanted a partner to design and build a microcomputer to accompanying its computer literacy programme, and ultimately to be the one to define and dominate the ballooning home computing scene.

“The personal story is fascinating,” she says. These two men that had a master-protegé relationship and knew each other and then went on to establish very successful businesses in their own right.”

“Go and set up Science of Cambridge, but ignore the Watch Calculator, will you?”

This was no simple race for the finish line: both rivals, each driven by the personality of their founders, soon became obsessed with beating each other at their own game - Sinclair to elbow past Acorn in the "serious" computing part of the market, Acorn to muscle in on the Spectrum’s ownership of gaming.

And perhaps, Andrea suggests - and the film was to show - therein lay the root cause of the collapse the market underwent only a few years later.

So a mine of drama, then, but also of comedy, to be found in the once advanced, now low-tech products of the period and in the personalities of the story’s central characters, Clive Sinclair in particular. Even more conveniently for someone pitching a TV movie, it was also a subject barely covered by existing documentaries, let alone dramatisations. More to the point, she thought, it would appeal particularly to the BBC, which through the mid-2000s won critical acclaim for a series of historical dramas set in Britain’s recent past, including Cambridge Spies, Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! and The Long Walk to Finchley.

And, of course, the Corporation itself inadvertently triggered the main battle between Micro Men’s two central characters.

The Commodore connection

Andrea is no techie, but she has a small connection with the Acorn-Sinclair story. She was a schoolgirl back then, the daughter of a local teacher who, she says, often brought home BBC Micros to play with. She grew up in Cambridge, home of both Sinclair Research and Acorn - and a fair few other British microcomputer pioneers too. No one in her family was involved in the technology world, she admits, but she remembers the Cambridge Phenomenon being the talk of the town.

Director Saul Metzstein, on the other hand, was an eager participant in the computer boom. As a young lad growing up in Glasgow his first encounter with computer technology was an Atari VCS bought by his architect father to appease a nagging Saul and his brother. A pal had a Pet. Later Saul upgraded to a Vic-20 and, a few years later, a Commodore 64. “I totally remember that from my childhood. I was 13 in 1984, and it all came flooding back to me,” he says, before describing a trip down from Glasgow to visit The Commodore show held in London at the Novotel. He was on a team that got to the quarter finals of the Scottish Schools Computer Quiz.

“I immediately knew I wanted to make the programme,” he remembers. Before he’d even seen a script, he had in mind a closing sequence showing “Clive Sinclair on a C5 with Jean-Michel Jarre playing in the background. Everything else worked back from that.” The juggernaut scene is one Micro Men’s most powerful, most telling scenes.

Outlining the Sinclair aesthetic

After spending some time doing preliminary research, Andrea Cornwell worked up a five-page treatment describing the story, which she took to BBC Four. “It met with an almost immediate, encouraging response,” she recalls, and she was commissioned to take the project to the next stage: to put together a package of director, leading actors and a writer. With a writer on board, pre-production research work would be collated and fed in to the script, which would then be judged by the BBC as to whether the show would go into production.

“Doing a project as an independent with the BBC is fairly straightforward in that you’re generally dealing with a single financier,” she says. “You are going to make the film for the budget they give you, and while there’s a little bit of wriggle room, there is normally a tariff for certain slots: You know a 90-minute drama on BBC Four will have a certain budget and you have to work out how you’ll make the film for that. And then it’s really just about finding talent that the BBC will get excited by.”

There was never any question about who ought to direct the story. Saul Metzstein and Cornwell had recently completed a short drama-documentary for Channel 4, Alive, and had worked in the past on a number of other short pieces. With Saul’s knowledge of the period and empathy with the subject, he was very keen to take it on.

“He absolutely remembered the period and was enthusiastic about the subject matter,” Andrea says. “He came from a background of independent film-making so had a very colourful, kaleidoscopic, visually driven style.”

Metzstein has found greater fame since Micro Men, as a one of the regular directors during Matt Smith’s time in Doctor Who: A Town Called Mercy, The Snowmen, The Crimson Horror and The Name of the Doctor are among his episodes. Most recently he took the helm on a couple of episodes of the BBC series The Musketeers, which co-stars the new Doctor, Peter Capaldi.

Hard at work in a former RAF base

When Andrea Cornwell approached him to write Micro Men, screenwriter Tony Saint had just completed The Long Walk to Finchley. Broadcast in June 2008, Saint’s show was widely praised for its apolitical, non-judgemental portrait of Margaret Thatcher in the years before she became Prime Minister. Saint’s script was more interested in exploring motivations and telling a story than playing to expectations based on what people knew of the politician Thatcher became. That was the tone Andrea knew she wanted for Micro Men.

It was a choice the BBC were keen on too, and though Saint is no computer buff himself, the story appealed to him and he had a sufficient window in his schedule to get it done. “For him it was all about this interesting cultural movement,” Andrea recalls. “You’re looking at a pivotal point in history. There’s not a person in the country today that doesn’t have home computing in their lives in some way. It is absolutely looking at the birth of something that is universal, and I think he liked that.

“We saw it as a Rudyard Kipling ‘Just So’ story: sort of, how the computer came to be.”

Two’s a crowd

And it got better the more the producer, director and writer researched it. “What was unusual about this story is that as you read more more about it, the more it became more like a classical story, rather than less,” says Saul Metzstein. “Usually when you research something real, there’s always some disappointment at the end of the story, but actually this is a classic: it’s two guys who were friends and brought each other down. The story got better and better the more you looked into it.”

But not a dry tale of business competition. “Both of us very early on realised we’d have to do it as a sort of comedy,” Saul adds. “I’m not sure we ever discussed it, it was just obviously a comedy. One of the reasons for that is, looking back, the technology is so comedic to our eyes now, so I don’t think you have really done anything very dramatic, anything like ‘My God! Now we’re on to 32-bit’. And it’s a classically British story, in a sense of it’s brilliant innovation followed by success followed by failure, and I think that has a poignancy.

“I hope there’s a degree of reverence too. I didn’t want to be sneering. I think if you’re just laughing at them, it’s not that interesting a drama either, because that’s just taking advantage of the fact that the past is primitive. I wanted viewers to feel for these guys.”

Nigel Searle (Derek Riddell), Clive Sinclair and engineering lieutenant Jim Westwood (Colin Michael Carmichael) consider the QL

One aspect of the production the creative team were unsure of was how much of the world outside of Acorn and Sinclair to include. An early draft of the script, says Saul, had a scene showing kids opening their Christmas presents and finding micros, but it was dropped because it didn’t fit into the main storyline. Instead, the computer fair and WH Smith scenes evolved to present a contemporary world and still feature the key characters.

Central to the telling the tale would be the experiences of the people who had participated in the events the film would depict. Cornwell, Metzstein and Saint met and interviewed all the key participants – Nigel Searle, Sinclair Research’s managing director, was a notable exception; they couldn’t track him down – and many other of the people involved in Sinclair and Acorn in the early 1980s, including a fair few who didn’t ultimately appear in the final screenplay.

“We tried to meet as many of the real characters as we could, and we were pretty successful,” Andrea says. “Not only the ones who are depicted in the film: we met an awful lot of the other people, most of them were very generous with their time. So the script was entirely based on real stories and real anecdotes. It was all verbatim - we didn’t make up any of these stories.”

Of course, some dramatic licence was necessary. “You’re trying to fit real life into a dramatic structure. As we all know, real life doesn’t always follow a perfect three-act structure, so you always end up with certain challenges if you’re looking at true stories,” she adds after mentioning the sequence where Acorn co-founder Hermann Hauser cuts an umbilical cord-like wire to bring the BBC Micro prototype to life seconds before Chris Curry enters the lab with the BBC’s representatives.

Hermann Hauser (Edward Baker-Duly) prepares to cut the cord

Steve Furber, now a professor of computer engineering at Manchester University but was there on the day, is happy with a considerable contraction of the sequence of events of that Friday morning. “In reality I think it leapt into life about three hours before the BBC arrived rather than three minutes afterwards, but the minor points don’t matter,” he says. “Whether or not I had a beard or wore glasses is minor compared with managing to extract an interesting storyline out of it all.

“The fact that the final thing that got the prototype to work on the morning was Hermann’s idea to cut this wire - which I think was just connecting the Earth from the development system to the card; I don’t think it was a clock - the fact that Hermann, who had really no idea what was going on, made the final suggestion that made it work is one of the ironies of the story which I always find entertaining. He’ll never forget it either.”

Furber was played by actor Sam Philips in the show, who sported glasses and a tank top, both arising from mistaken identity: specifically a photo of the Acorn Atom held by all the key Acorn contemporaries - other than Steve Furber who hadn’t officially joined Acorn at that point. Philips’ look was thus inspired by David Johnson-Davies, though neither he nor Furber were bearded as Philips is in the show.

There is one Furber-lookalike in the programme, however: “All my family tell me Peter Davison looks remarkably like me,” Steve says.

The man who brought you Jet Set fucking Willy

Davison’s casting was very deliberate, says Andrea Cornwell - she and Saul Metzstein wanted to include some faces familiar from early 1980s TV. “We had a small, tongue-in-cheek nod to the period in some of the small parts, we had a Doctor Who in there, and we had people from Blake’s 7,” she says. The latter - singular, not plural - was Michael ‘Villa’ Keating, here playing Derek Holley, Sinclair Radionics’ National Enterprise Board-appointed Finance Director.

“We met a lot of people for the different roles,” Andrea remembers. “The biggest challenge always with this kind of piece is how much you try and find people who look like the originals. Apart from Clive Sinclair, the general public doesn’t know what these people look like, but we did try to an extent to match photos of these people from back in the day, and that limits you in the casting.”

Casting the two lead roles was governed as much by the need to find actors who the BBC would be happy with, as people able to inhabit the personalities of the main characters. Alexander Armstrong, who was keen to do the programme, was chosen for his ability to convey Sinclair’s clipped tones and handle calm interview discussions as well as explosive rages. Stephen Berry, a software engineer who worked at Sinclair Research from 1981 to the end feels that, exact resemblance aside, Armstrong nailed Sir Clive, and the show captured the the atmosphere at the company almost perfectly.

The Doctor and the Professor: has anyone ever seen Peter Davison and Steve Furber in the same room at the same time?

“I tried to convince Alexander to shave his head,” Saul recalls, “but he was about to record a series of the game show Pointless, so they would have had to wig him or have a skinhead thing going on. If I was to do one thing different were I to do the programme again, I wouldn’t use the bald cap. It was very accurately modelled on Sinclair, but once the audience thinks the actor is Clive Sinclair, they don’t care.”

Martin Freeman was certainly a good choice for winning over BBC Commissioning Editors, though Saul remembers Chris Curry’s daughter, on hearing who was to play her father, expressing concern that her dad would be associated with that wimp from The Office, a reference to Tim Canterbury, Freeman’s character in the show.

“With Chris Curry, he was played a little too straight, from my point of view,” says Steve Furber, who of course knows all the Acorn folk. “Martin Freeman played him very much as the straight guy who was very much beaten about by Sinclair. In fact Chris has quite a sly side to him. He’s a bit more into low cunning than he was played.”

But Furber praises Micro Men’s portrayal of his other former colleagues. “I thought they got as close to Hermann as you could expect an actor to do,” he says. “They conveyed Sophie’s cleverness and slight arrogance that went with it, I was more of a regular engineer so any argument over facts with Sophie I would lose because she has the kind of sponge-like memory that holds an infinite number of things that I generally forget.”

Will the real Jim Westwood step forward? There he is, at the back, in WH Smith

With the script complete and a provisional cast in place, Andrea Cornwell returned to the BBC to seek final budgetary approval and the go-ahead to begin filming. The green light was lit in April 2009, and filming began almost immediately.

Shooting took place over a 20-day period, all that the budget allowed. That’s a heck of a short time for a 90-minute feature, says Saul Metzstein, and left no time for rehearsals. He praises the professionalism of all the cast, who learned their lines and, apart from a few pointers and an hour or so’s briefing for the two leads, just turned up and got it right.

Director and producer had already scouted the key locations, finding many had changed considerably in the past 30-odd years. A day was budgeted to shoot establishing shots in and around the town; it did not go well, but there was sufficient suitable footage at the end of it. “We found Sinclair’s old offices in King’s Parade opposite Kings’s College Chapel were occupied by a new IT company called Collabora so managed to get in there and shoot some views out of the windows,” says Andrea.

Collabora, incidentally, specialises in open source software development and is currently developing Wayland, the would-be successor to Unix’s X11 windowing system, for the Raspberry Pi. In fact, Collabora were at number 11 Kings Parade; Science of Cambridge and Sinclair Research were at number 6.

Base of operations

Almost all of the interiors were shot at the former RAF West Drayton, close to Heathrow in Middlesex. “It had fantastic Cold War interiors, quite a lot of 1980s outside buildings and a real variety of architecture,” Andrea says. “We wanted something that could serve as the typically 80s modern glass and steel structure Clive bought on the outskirts of Cambridge.

"We took over one lower block and turned that into the early Acorn offices. Our art department did a fantastic job putting it all together.”

Kudos then to art director Tim Stevenson and his team - responsible for the period paperwork and such - and to production designer Chris Roope, for devising suitably 1980s-like interiors, in particular the spookily accurate WH Smith shop, as anyone who used to lurk in the shop in order to mess around with the display computers will attest. Before Micro Men, Roope had been production designer on The Full Monty and on the Ian Curtis biopic, Control. He also worked on British comedies Thunderpants and the Nativity! films, both alongside Stevenson.

The reason for the single site was budgetary. Low-budget dramas tend to be shot in single locations which can accommodate all the production departments: props, costumes, art and so on. “Micro Men wasn’t written to be in one location. It covers a number of years, it covers different companies, houses and commercial spaces. On the face of it, this is not a particularly sensible project to be plunging onto with a BBC Four budget,” says Andrea. But having the base allowed the team to operate is if it was a single-location shoot. “Eighty-five per cent of what you see one screen - from the computer fair to WH Smiths to the offices - were all shot on the Air Force base.”

First the Corporation, then the Government: Kenneth Baker (James Fleet) backs the Acorn BBC Micro

There were problems, however. A week before shooting, the availability of the RAF West Drayton was suddenly in question: Cornwell and co were told the bulldozers were going to arrive in the very near future. “It was a site that was due for demolition anyway, so sadly it doesn’t exist anymore. Parts of the site were being dismantled as we were shooting. We only just managed to squeeze it all in.”

Not every part of the production was recorded on the base. Scenes set inside Sinclair Radionics’ HQ, The Mill, were shot in an old Victorian warehouse building in Wapping. Clive Sinclair’s home was shot in a real house near West Drayton. The Cambridge University Processor Group meeting room, when Chris Curry and Hermann Hauser first meet Steve Furber, was taped in a West Drayton school, though the shot of the men ascending a staircase beforehand was recorded on the base.

The closing sequence, in which Alexander Armstrong, riding in a real, flimsy, exposed-to-the-elements C5, is overtaken by Microsoft- and HP-branded juggernauts, was shot around the corner on a test track. The C5 was real, though the prototypes seen in the show were made by the art department from photos and other documents. Oddly, none of the crew wanted to take the C5 home with them when filming ended...

Roger Wilson (Stefan Butler) and Steve Furber (Sam Philips) sort The Computer Programme out with a program

“Clive and Chris used to meet in a Little Chef, but we didn’t get permission to show their logos, so we ended up shooting that scene in a closed down roadside cafe,” Andrea remembers.

The interior of the Baron of Beef, site of Sinclair’s famous bust-up with Curry, was actually a pub in West London, though the crew photographed the real pub’s frontage, Saul notes. The dialogue - “You fucking buggering shit-bucket!” - was taken verbatim from Curry’s telling of the tale, though the fists flew in Shades Wine Bar, not the pub. Saul admits they necessarily compressed the two locations into one.

“We did a few street scenes, bits where Clive goes jogging, all within striking distance from our main sets,” Andrea continues. “Street scenes are the bane of your life when you’re doing period piece. It’s a matter of choosing your camera angles very carefully, and making use of the old tricks of parking a couple of period vehicles in front of things that don’t work, and a little bit of VFX just to smooth the edges and get rid of satellite dishes.”

Photography complete, Micro Men went into post-production: the visual effects Cornwell refers to, mixing in the soundtrack and editing the piece together.

Archive hour

“The finished film has an awful lot of real-life archive footage in it, that was one of the early decisions we made: to try and do present Micro Men in a way that benefited from all this stuff, to try and give it a sense of authenticity,” she says. “We looked very much at films like Milk, Sean Penn’s 2008 story of San Francisco mayor and gay rights activist Harvey Milk, which set up a very bold style from the outset, where they just slam in archive and cut it in with live action, modern-shot material and it just becomes part of the visual style of the piece.

“We wanted to make people think, ‘I remember that’.”

Not just archive material but 1980s TV technology played a part too. Saul Metzstein applied series a series of picture-in-picture effects during the show’s epilogue to bring to viewers’ minds the Quantel effects of the period. “We also tried to shoot it quite crudely,” says Saul. “I couldn’t shoot it on film; it’s too expensive to do that. So we used older, cheaper video cameras, and for the exteriors we used a lot of very, very big zoom lenses because it’s a style of shooting they used to do in the '80s.”

Grain was added in post-production, and the colours graded to reduce their saturation. Then there was the chain-smoking, a cliché for conveying the not-too-distant past and of periods of intense work and stress. Steve Furber puts the mockers on that one: “I haven’t touched a cigarette since I was 12, I think. I was a non-smoker. I suspect Chris Curry, who was a smoker, probably smoked in his private office, from time to time, as did one or two other members of staff, but no one smoked in meetings and certainly people didn’t smoke in shared spaces like labs and so on. That was very unpopular.”

Sinclair takes it out on Curry

Music naturally played an important part in the show’s verisimilitude. Not rock and pop tracks from specific years, but rather tracks associated with the period: Vangelis’ Pulstar, Jean-Michel Jarre’s Zoolookologie and Oxygene IV, Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Two Tribes, Nena’s Ninety-nine Red Balloons, Paul McCartney’s Pipes of Peace and Pink Floyds’ Another Brick in the Wall, plus themes from contemporary BBC shows: The Money Programme (the main title from the movie The Carpetbaggers), The Computer Programme (Kraftwerk’s Computerwelt 2) and Making the Most of the Micro. All readily useable, thanks to the BBC’s blanket licence, but unhappily ensuring we’ll never see a commercial release.

Preliminary edits were shown to key participants. “I sat and watched it with Clive Sinclair,” says Andrea Cornwell, “and he said a few times, ‘it wasn’t like that’. So we did change a few small bits based on that feedback.”

According to Saul, so tightly was the story told in the script, and so rigid the budget, that almost no sequences were shot which did not make it into the final cut. A scene between Sinclair and his first wife, Ann, who he divorced in 1985, was cut because it contributed little to the story and, once filmed, was considered unnecessarily intrusive into Sinclair’s private life.

Saul remembers Chris Curry and Herman Hauser telling a hilarious story about being summoned to the Olivetti headquarters after the Italian firm saved Acorn from collapse, but hadn’t fitted smoothly into the script so was alas never included. Similarly, it wasn’t possible to work in the other problems which played a part in Acorn’s near-terminal woes, he says, most notably its expensive attempt to break into the US market, a scheme that proved a complete failure.

Overtaken by the juggernauts

Inevitably, though, there is no single story here. All the people involved were telling their tales 30-odd years after the events being described took place, and the production team had to navigate through those differing opinions “in all their full contradictory glory”, as Steve Furber puts it.

“For instance, if you talk about the initial competition to get the BBC Micro,” says Cornwell, “of course you will get a different story from the Sinclair team than you do from the people working on the Acorn proposal because they have a different perspective. That’s part of the point of the story. You can never find an ultimate truth because it doesn’t exist. You are dealing with different peoples’ opinions and experiences.”

The resulting programme is, as Steve Furber puts it, “a good yarn”. Technology buffs can list all the errors they like - here are three: Amstrad bought Sinclair in 1986 not 1985, as one closing caption states; Acorn’s first machine was the System 1, not the Atom; the list of companies bidding for the BBC Micro contract is incorrect - but that’s true of any if not all dramatisations of historical events. This one is true to the events themselves. For me, it conveys the tone of that exciting, pioneering era perfectly. It portrays the characters truthfully and honestly.

Micro Men is, after all, a play not a documentary. It’s for others to detail the history of that period. Micro Men is meant to inform, but above all it’s meant to entertain. And in that it succeeds admirably. When it comes to reliving those days, short of whipping out an old micro and having a few tapes fail to load, there’s little better than an evening with the Micro Men. ®