Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/12/13/uk_innovation_nesta_fentem/

How Britain could have invented the iPhone: And how the Quangocracy cocked it up

Inventor screwed - while taxpayers sent a clown on holiday

Posted in Channel, 13th December 2013 10:04 GMT

Special Report This is a disturbing, cautionary tale of quasi-government and its bungling. It describes how Britain could have led the recent advances in touchscreen technology, developing kit capable detecting more than one fingertip at once, years before Apple did – if it weren't for the nation's treacle-footed, self-serving quangocracy.

Today, thanks in large part to the multi-touch graphical interfaces in iPhones, iPads and iPods, Apple has turned itself into the biggest tech company in the world. The Cupertino goliath could have entered the mobile phone market well before 2007, but it waited for a leap in user-interface design that enabled the manipulation of on-screen things using one or more fingers – pinch-to-zoom and similar gestures, in other words.

The success of the iPhone and iPad was a generational “paradigm shift”, and companies that failed to move with the touchy times include fallen giants Nokia and BlackBerry.

And that seismic shift so easily could have been based on a British invention.

Our saga begins with Andrew Fentem, an electronic engineering graduate and former Thorn EMI engineer who – after a few years working on defence projects – was at the University of Cambridge and the London Business School doing a PhD. There he’d developed software to arrange and display data in new and visually interesting ways, and called it Spatial Hypertext Object Management System, aka SpaceMan.

“It was like a fancy Pinterest system,” he recalled to The Register.

“It was easy to build attractive applications, but I found the lack of tangibility and tactility uninspiring, so in my spare time I decided to do something about it.”

Thus in Fentem’s free moments, beginning in 2001, he designed and built a physical user-interface gadget that went beyond the traditional mouse and keyboard: a flat matrix of hairs, rollers, vibrators, electromagnets and other actuators that could move around objects. Automatically arranging things on a board is one thing, but sensing where the user had moved them is another.

“I needed a way of tracking these multiple objects, and that's where my interest in multitouch systems started," says Fentem. "I eventually started working on these technologies full-time, and progressed to developing high-speed multitouch touchscreen systems for games like virtual air-hockey, interactive carpeting, and for multitouch virtual synthesiser controllers.”

That multitouch sequencer can be seen in action below; notice the instrument controls are simply blocks positioned on the flat sensor surface:

By this point Fentem had quit his PhD, and spun out the data visualisation software into a management consultancy, reinvesting the money to focus on the multi-fingered user-interface problem.

“I was unique in that I had built an entire system - hardware, signal processing, operating system, and application layer from the ground up, before Apple had,” he said.

Indeed, when Samsung needed an expert to defend itself in court against Apple's allegations of touchscreen patent infringement, Fentem was called to be the South Koreans' expert witness in the European rounds of litigation.

Multitouch clearly had plenty of uses. How could an inventor bring some of these to market? Obviously, Britain's then-Labour government was here to help.

Enter Nesta

The UK’s National Lottery was launched in 1994 - five years before Fentem ended his PhD studies in 1999 - to (besides turning a tiny number of ordinary folk into millionaires) pump cash into worthy arts, sports and heritage projects. But the New Labour administration, with which Tony Blair swept to power in 1997, wanted to extend the brief to support innovation and entrepreneurs. Playing venture capitalist wasn’t in the original plan, and required a revision to the Lottery Act in 1998: this created a quango dubbed the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (Nesta).

Nesta had three grandiose ambitions:

- It would “help talented individuals (or groups of such individuals) in the fields of science, technology and the arts to achieve their potential”.

- It would help people “to turn inventions or ideas in the fields of science, technology and the arts into products or services which can be effectively exploited; and the rights to which can be adequately protected”.

- Thirdly, it had a vague remit of "contributing to public knowledge and appreciation of science, technology and the arts". Which could mean almost anything.

Nesta began life in 1998 with a £250m endowment, using the interest on the sum to fund its activities. Its first chairman was Labour supporter and donor Lord Puttnam of Queensgate.

He was succeeded by top adman Sir Chris Powell, who, as the son of Air Vice-Marshal John Frederick Powell, belongs to one of the most powerful and influential families in British public life. Sir Chris's elder brother Charles, now Baron Powell of Bayswater, was an ambassador and private secretary to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. His younger brother Jonathan became Blair’s Chief of Staff in Downing Street, a title created by the incoming premier, granting Jonathan unprecedented power over civil servants. Meanwhile, Sir Chris headed the advertising agency BMP, which was used by Labour from 1972 to 1997.

Today, Nesta is chaired by the controversial Sir John Chisholm, the legendary public-sector corporate raider. Chisholm was chosen in the dying days of the Tory government to organise the selloff of much of the Ministry of Defence’s R&D capability as a private company called QinetiQ – and then became QinetiQ’s head, turning a £129,000 personal investment in the company into a £23m payout.

Fentem submitted a funding application to Nesta in January 2003, while he continued to work on new prototypes.

"When I first approached Nesta I was told that I would receive a funding decision within 6 weeks," he says. "However, it took Nesta a year to just write the contract. To put that in perspective, it took Apple only 2 years to conceive, develop and commercialise the entire iPhone."

'No one at Nesta has a science or engineering background'

It would be many months before the organisation's bureaucracy finished processing his paperwork. Fentem said he had been troubled to learn, that spring, from a manager at the quango that that “no one at Nesta has a science or engineering background”, in the manager’s own words.

“When he saw the look of horror and disbelief on my face he quickly said, ‘But we're trying to remedy that’,” Fentem recalled.

That August, Nesta introduced him to a potential manufacturing partner, but there were more delays – in all, it would be almost a year before a funding deal was signed. On 5 November, Fentem inked a contract with Mark White, Nesta's Invention and Innovation Director. The deal assigned Fentem a mentor, earmarked a manufacturer, and released £20,000 in funding. Another £30,000 could be unlocked later on once further progress was made, as well as £50,000 to develop an initial product.

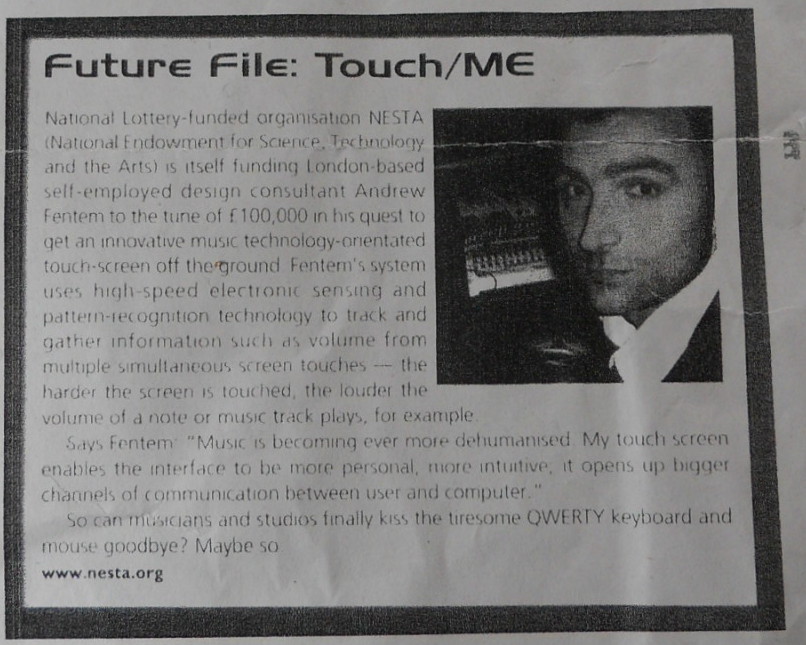

The contract describes the development of “an innovative touchscreen technology”, specifically a touchscreen that can detect the speed at which one's fingertip moves across the display and can "capture multiple impacts across a surface area" – multitouch, in other words.

“A number of sectors within the music industry would benefit from such a device”, the agreement notes, adding that “the idea has potential uses beyond the music industry and could be developed into mainstream computer hardware”.

But the deal turned out to be pretty one-sided. Fentem explains:

The manufacturing deal "milestone" created something of a chicken and egg impasse; Nesta wouldn't release the funding until the technology was ready for a manufacturing deal. In other words, I was expected to complete development of all of the multi-touch technology with my own savings plus their 20K investment, shouldering most of the project risk - Nesta were mainly exposed to what bankers call "up side" - i.e. they would only "invest" when they were almost guaranteed royalty returns. This is not normal.

Send in the Clowns

Was Nesta truly committed? The sum seemed paltry compared to some other grants the outfit was dishing out.

In 2003 the press reported that Angela de Castro, a Brazilian-born clown, had won £39,200 for a study to “evolve her clowning expertise and look deeply into what clowning has to offer contemporary society”, according to Nesta. That cash also covered travel expenses so the performer could learn from “master clowns” around the world.

Requests for jaunts were favourably received. Later it would emerge that Nesta spent over £1m on “dream time fellowships”, which encouraged artists to take a year off to "explore". According to a 2005 Sunday Times report (behind paywall), one received £27,500 to monitor her moods and compare them to phases of the Moon. A magician received £36,890 grant to travel to Las Vegas to see another magician perform at the Sahara hotel and casino ("Lotto pays out £1m in grants to mood watchers" – by Maurice Chittenden and Holly Watt, Sunday Times, 19 June 2005).

Nesta’s apparent frivolity didn’t stop there. The Lottery Act that had created the outfit urged it to protect an individual’s intellectual property (IP). Yet, astonishingly, even before Nesta had signed a contract with Fentem, we're told it published the details about his work on its website, alerting competitors. Nesta, meanwhile, maintained it had provided a "one-line description of his project published in a bulletin without his approval, but denied that any intellectual property rights had been infringed by [the] disclosure".

The quango would later admit that it didn’t recruit “intellectual property practitioners” as a matter of policy - but instead would “obtain IP advice to inform our processes ... by engaging relevant experts as the need arises”.

The clock continued to tick, and in April 2004, Fentem wrote to Nesta, impressing upon them the need to unlock sufficient funding for the project.

“My project is positioned both literally and metaphorically on the periphery of the computer industry, and industry that is fast moving and high risk, but at the same time offers huge rewards. The investor needs to act quickly and decisively,” he urged the organisation.

“Since I applied to Nesta for funding, companies such as Sony have started to turn their intense beam of their R&D division’s searchlight onto the kinds of technologies I have been developing.”

Fentem proposed approaching Apple and Sony with his technology that very month.

Nesta had introduced Fentem to a potential manufacturing partner, electronic music equipment maker Novation EMS. But Novation EMS was going bust. In June 2004, it had entered administration and by August, its assets were gobbled up by Focusrite. In a later PwC report, the investigator contends that the company "had demonstrated a weak balance sheet from the start", requiring cash to be paid to them directly for the development, indicating they may have had a short-term cash problem".

Fentem was now in a bind: In his view, Nesta had alerted competitors to his innovative multitouch work, but its foot-dragging had led him down a costly dead end. The quango refused to release any more money until he found a new "development partner".

"Bear I mind I had been given just £20,000. I had done an extraordinary amount for so little money."

As to looking for a development partner to "unlock the funds" for "development", Fentem said: "We thought we'd made a lot of progress on development. They said money hadn't been released because some arbitrary milestones hadn't been reached."

In an internal review conducted in December 2004 which The Register has seen, Nesta itself conceded that "milestone" requirements [were] not set out sufficiently clearly in the contract to provide certainty on when they have been met." It continued: "Milestone renegotiation issues can only be resolved through discussion between awardee and programme staff...to identify a way forward."

But Nesta and Fentem could not reach an agreement. He told us: "They wouldn't acknowledge that they'd wasted such an enormous amount of my time."

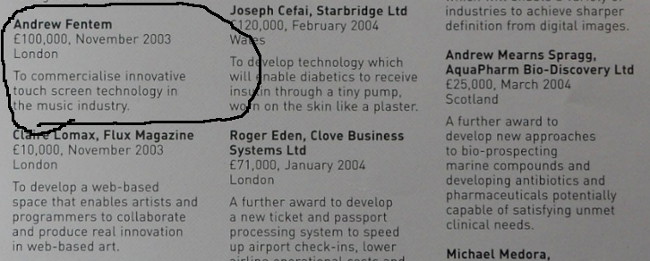

To add insult to injury, Nesta continued to claim publicly it had invested £100,000 in his multi-touch screen tech.

From Nesta's annual report of 2003/04

Fentem demanded an explanation, and eventually this triggered a formal investigation by PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

Probing Nesta

During its initial, limited foray, PwC didn’t investigate the conflict of interest relating to Fentem’s assigned mentor's liaison with Novation – nor did it examine whether the mentor should have informed Nesta and Fentem that Novation was in severe financial difficulties. PwC said in its first report that it was not within its scope to judge whether Nesta had been correct to freeze the multitouch project’s funding.

But in a later expanded PwC investigation, it found that despite "a potential conflict of loyalties" which occurred when it transpired that Fentem's mentor had been separately acting as Novation's advisor as well as working on behalf of the inventor, "there [was] no evidence this caused any detriment to the complainant's project". It also noted that the Project mentor's position with the manufacturer had been "unpaid" and "informal".

It did however, note that the potential conflict of interest should have been registered at the time and added that there was not "sufficient guidance on conflicts ... for Nesta's Project mentors".

Emails obtained via FOI which The Register has seen revealed that when the report was delivered, NESTA executives internally considered asking PwC to amend its report in relation to the final point about the "potential conflict of interest".

It is worth noting here that Nesta did not do this.

Nesta did not contest the finding.

“I am very sorry that in your case, we fell short of the high standards you should expect from NESTA,” wrote CEO Janet Morrison in March 2005, after the PWC probe partly upheld Fentem's complaint.

Morrison confirmed that for Fentem to receive the remaining £80,000 to continue his work, he would have to agree that Nesta take control of his efforts again – trusting the same organisation that, from the inventor's point of view, had delayed the project for nearly two years. Nesta maintained that Fentem needed to find a new development partner before the funds could be released.

The initial internal review by Nesta had partly upheld Fentem's complaints that the "10 months it took [Nesta] to process [his] full application exceeded Nesta's published service standards which state that applications will be processed in 10 to 14 weeks". Later, the PwC review added that a decision not to pursue collaboration with Novation could have been taken in March rather than June and may have resulted to avoid a consequent three-month delay to the project.

Writing letters

So Fentem began to pursue the new Labour establishment – and found help in the form of his constituency MP, Emily Thornberry (Lab., Islington South and Finsbury), now the Shadow Attorney General. As they pressed to find someone to take responsibility, they struggled to get the actual government to exercise any oversight over its quangocracy.

Bodies which should have investigated the scandal failed to do so: the Ministry of Fun (aka the Department for Culture Media and Sport), the National Audit Office, and the Parliamentary Ombudsman. Perhaps most surprisingly, Thornberry repeatedly attempted to engage the Parliamentary and Health Ombudsman - Dame Ann Abraham. The Ombudsman sounded ideal: the position had been created to investigate malpractice in public bodies on behalf of citizens.

Yet Fentem claims that each request to investigate Nesta was turned down by Abraham. Her office cited a clause in the 1967 Parliamentary Commissioner Act which allowed it to “exercise its discretion” not to investigate contracts. The parts of the complaint which did fall under its remit, it declared, were so “entwined” with the contracts that its hands were tied.

Any outcome of an investigation into these matters would not achieve any meaningful result in view of the fact that there are statutory restrictions on our ability to address the key issue of alleged actual financial loss. The most we could achieve for Mr Fentem if an investigation were to find maladministration, is a review of the complaints and conflict of internal procedures at NESTA, review of the processes used to select development partners, and an apology.

A former council official, ombudsman Abraham had launched a project called "Ombudsman's Principles" which took two years to define what an Ombudsman should do. Proudly enshrined in the 2007 publication "Principles of Good Administration", these included "Getting it right", "Being customer focused", "Being open and accountable", "Acting fairly and proportionately", "Putting things right" and "Seeking continuous improvement".

Later dubbed “the Quango Queen”, Abraham retired with a £1.45m pension pot in December 2011, claiming £9,100 on hotel expenses in her final nine months in the job. Her career had included spells at the quangos Housing Corporation, the Benefits Agency and the National Association Of Citizens Advice Bureaux and the Committee On Standards In Public Life. She also acted as the Health Service Ombudsman for a full nine years, until just two years ago, in 2011.

Abraham's office argued that any compensation in Fentem's case would be “consolatory” rather than full compensation of the commercial opportunity lost. Reluctantly, Fentem and Thornberry agreed to forego fair compensation. While Fentem had lost an incalculable amount, perhaps future inventors would receive better treatment. They urged Abraham to open an investigation, merely to hold the quango to account.

In June, Abraham again refused: “I need some evidence of maladministration," she wrote.

The Breakfast Club

By 2006, Nesta had become too embarrassing even for the DCMS. The old I&I department was effectively disbanded. But soon it was back.

“This has been a year of good progress for NESTA,” wrote Chairman Chris Powell in the foreword to the 2007 Annual Report (PDF).

Powell trumpeted a new “Intellectual Property Accelerator that helps creative entrepreneurs make the most of their intellectual property.”

The report goes on to detail that NESTA had developed “a new strategic direction” entailing a “realignment of programme streams”. But what was in the water, and where would the streams flow?

The quango also moved to BIS, the biznovation department, from DCMS in 2007. It had become a talking shop; the new Policy and Research Unit would become “a hub for the policy and research community around innovation”. Still, Powell seemed pleased by the changes:

In November 2006 we moved to our new offices in Plough Place in London - a truly inspiring space, which is already recognised as a physical hub for individuals and organisations to meet, swap ideas and network.

But the relentless technology market didn’t cease. Remember that Fentem had urged NESTA to approach Apple in March 2004. In early 2005, Apple instead acquired Fingerworks, a company founded by an electrical engineering student – just like Andrew Fentem – called Wayne Westerman. Westerman’s PhD dissertation was titled “Hand Tracking Finger Identification and Chordic Manipulation on a Multi Touch Surface” and he’d managed to produce commercial products within three years.

Spanning as it did science and the arts, Fentem’s work was arguably much more flexible and sophisticated than Westerman’s keyboards and much more closely aligned with Apple’s vision.

Today, the iPad is capable of manipulating images and driving virtual instruments – and this was all work Fentem was perfecting in 1999, work that had to be “relearned” by Apple after acquiring Fingerworks. Acquiring Fentem's potentially superior British technology could have allowed Apple to bring products to market faster.

But thanks to the bungling British quangocracy, Apple never even saw his work.

In fact, in a bizarre twist, Nesta actually contacted Fentem asking for royalties statements, gross receipts and updates on his trading status the following year in a letter seen by The Register.

In its first five years handling a £250m endowment, NESTA saw a return of just £228 in royalties ("Puttnam fund hit by row on ‘follies waste’" - Sunday Times - behind paywall).

“A few years ago,” Fentem recalls, “I was interviewed about my work by the British Council - the article was for a magazine distributed by their 'creative embassies' around the world. After the usual questions about my influences etc, they asked me what my message would be to young people thinking about coming to work or study in the UK.”

“I said, 'Don't'. 'Don't what?' asked the woman from the British Council...'Don't come. Don't come to the UK....that would be my message'."

The Aftermath

It would not be fair to say everybody has been a loser in this story. Certainly, the inventor and the British technology industry and the British economy lost out. But for many others, life has been kinder.

In recent years the determination to throw taxpayers' money at “innovation” is a belief held with something resembling a religious mania. The result is a complex web of taxpayer-funded agencies that create a kind of self-perpetuating talking shop.

Nesta itself was earmarked for closure prior to the anticipated “bonfire of the quangos” – but instead the Conservative-led Coalition of 2010 gave it a new lease of life. Although it became a charity, it retained its endowment.

Geoff Mulgan, founder of the thinktank Demos and former director of No. 10’s Policy Unit, became its head. After being repurposed “to improve the innovative capacity and the innovation systems of the UK”, it is once again investing in startups.

“NESTA became the UK's single biggest seed capital investor, which is something that we probably all applaud,” said Baroness Hayter in the House of Lords.

What should the state fund?

One of the high priestesses of the religion of state intervention in innovation is an American, Professor Mariana Mazzucato of Sussex University. Mazzucato’s book The Entrepreneurial State has made her one of the BBC’s favourite economists.

"Yes, innovation depends on bold entrepreneurship. But the entity that takes the boldest risks and achieves the biggest breakthroughs is not the private sector; it is the much-maligned state," according to one review of The Entrepreneurial State. And there's truth in that, though it is generally the nasty old Defence department - not the biznovation bureaux - which makes most of a state's real tech breakthroughs (computers, integrated circuits, space rockets, jet engines, packet-switched networking, satellite navigation etc etc).

But apparently the state does more. According to Mazzucato, as cited by Polly Toynbee, “huge state investment in touch screens” gave Apple its advantage. Mazzucato went further: “all the technologies that make the iPhone ‘smart’ are also state funded”. [p112] For Mazzucato, the state had made “an investment” in Westerman’s multitouch but failed to “recuperate” it. [p72] (sic)

Critics and academics laud Mazzucato for her critique of “neoliberal capitalism”, for challenging “the neoliberal orthodoxy”.

But for the patient Fentem, Mazzucato’s take on what had become part of his personal history was too much. In response to a superficial but positive review of Mazzucato’s book by Martin Wolf, The Financial Times published a letter from Fentem in which he pointed out that in Britain at least, "state entrepreneurship" didn't work - in particular on the matter of touch screens.

He had been forced to use his own savings to fund pre-iPhone multitouch technology, because “the UK government body that promised to support the development and commercialisation of the research work (Nesta) had failed to transfer the bulk of the funding I was awarded. Its main priorities seemed to be institutional self-preservation and public relations, rather than supporting entrepreneurship”.

Analysis

The enthusiasm for Mazzucato’s proposition of investment from publicly funded agencies is boundless – but is this really healthy for UK plc? Mazzucato embodies the problem: receiving as she did generous funding from the state (her three-year FINNOV project was funded by the EC) to laud the virtues of the state directing innovation investment.

Fentem’s criticism that the politically homogenous nature of public appointments is unhealthy is certainly supported by the evidence. More than 77 per cent of people with political backgrounds who were appointed to public bodies last year were aligned to Labour, noted the Times' Alice Thomson.

“Tony’s cronies are still with us and Gordon’s men have dug in. Labour understood how to play the quangocracy. They encouraged their supporters to apply for junior positions on boards and in organisations and watched as they rose up the ranks to positions of power and influence,” noted Alice Thomson in last year. (Who runs the country? It’s Labour, actually - Alice Thomson, 28 November, 2012)

One area in which the new "third sector"/quangocrat establishment dominates is innovation investment - it has become a powerful new class, for whom talking about innovation has largely replaced innovation itself. And here, it insists on taking control.

Amazingly, the rise of this micro-managing technocratic priesthood was predicted some 40 years ago by historian Daniel Bell. This academic-bureaucratic class even has a name: American sociologist Joel Kotkin calls it a "Clerisy". The Clerisy benefits, Kotkin explains, by increasing its role in directing investment - often to pet projects and causes.

"There are simply too many politicians and economists in the UK promoting stories and myths based on second-, third- or even fourth-hand experience of the world, because they only ever talk to other members of this 'elite'," Fentem opined. "It seems to me that every economist has a 'product' that is evaluated in terms of not how it explains or predicts real events, but how it will shape their media profile."

The Register contacted Nesta's current executive director of policy and research, Stian Westlake, for comment. Today's Nesta operates as a charity rather than a quango, and provides what Westlake describes as "catalytic funding for things at a very early stage" (BIS's Technology Strategy Board now does the lion’s share of governmental investment.)

Westlake said: "There’s been a growing recognition that innovation is not just about having good ideas but in making them real. It’s a long-standing – 100+-year-old – complaint about Britain that we invent lots of great stuff but someone else makes money out of it. This means that innovation includes not just R&D, but taking products to market, developing new manufacturing processes, understanding customers and other things that happen away from the lab."

When we asked him if there was an institutional bias against profit-making, Westlake responded: "We’re keen for the businesses we back through Nesta Investments, for example, to be profitable in the long run (we’re an early stage investor, of course, so this isn’t overnight and sometimes unfortunately not ever)."

The Register attempted to get comment from Mark White, who was Nesta's Invention and Innovation Director when Fentem was developing his multitouch sequencer, and Chris Powell, who was chairman of the organisation at the time. Neither had responded at the time of publication, but we'll update if we hear from them.

Labour's Emily Thornberry, Fentem's ally against the quangocracy back in 2004-5, agrees that if the state is to get into directing investment, it must do so competently.

"We have a commitment to growing our way out of recession, and this needs not only some forward thinking, but institutions that are fit to be able to deliver on this. Mr Fentem's story showed NESTA was not up to the job," Thornberry says today.

Andrew Fentem’s story is a salutary warning to actual technology innovators - as opposed to digital media types, popup coffeeshop proprietors etc - of the dangers of getting involved with Britain's new establishment. In Part Two we'll bring you the full interview. ®