Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/11/13/archaeologic_the_research_machines_380z_story/

The micro YOU used in school: The story of the Research Machines 380Z

As old as Star Wars, one of Britain's first true microcomputers

Posted in Personal Tech, 13th November 2013 10:04 GMT

Archaeologic If you’re a British techie of a certain age, there’s only one microcomputer that defines your first memories of computing at school. No, not Acorn’s BBC Micro – the Research Machines 380Z.

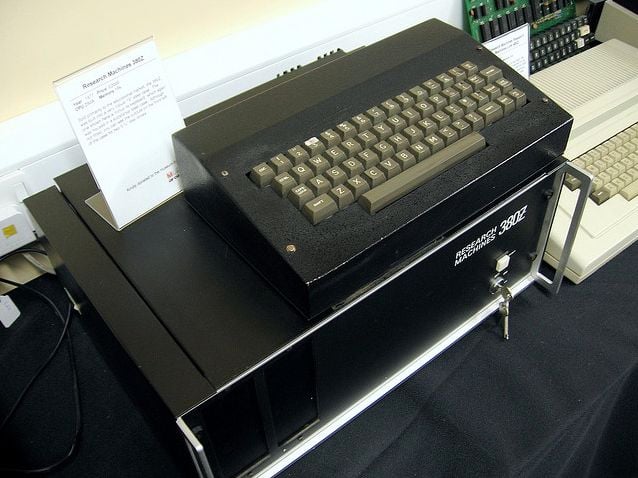

While Acorn was still knocking up the Proton, the machine being designed as the successor to the Atom, and while the BBC was pondering how it might possibly inspire Brits with the Joy of Hex, a number of far-seeing schools and colleges had already begun putting micros into kids’ hands. Most of them were doing so with Oxford-based Research Machines’ 380Z, a Z80A computer in a big black box with two handles on the front and clearly intended to be slotted into scientific instrument racks.

Schools’ micro: the Research Machines 380Z

Source: Marcin Wichary

The 380Z was the first computer I ever used to write programs – a rather poor text-only adventure, since you ask – though it was mostly used to play Space Invaders and a version of Computing Today’s RPG, The Valley. It wasn’t a colour computer, so it was soon supplanted in my imagination and those of my schoolmates by the Spectrum, the BBC, the Dragon 32, the Commodore Vic-20 and others.

Little did we know that the 380Z – along with its by then long-defunct sibling, the 280Z – was a pioneer of British microcomputing. In 1982, at the time I was first experimenting with Basic, the 380Z was already more than five years old.

It had already outlasted the early board computers it was launched alongside. It had survived the arrival of newer, low-cost cased machines like the Tangerine Microtan 65 and the Science of Cambridge ZX80. It had held its own against those slick US imports the Apple II, the Commodore Pet and the Tandy TRS-80 Model I.

Even in 1982, then, the 380Z was a veteran. It was a survivor. And it would live on for another three years, through the introduction of its successor, the Link 480Z, which débuted in 1982. This, then, is its story.

The tale starts in 1973, when two youngsters, Mike Fischer and Mike O’Regan, decided to enter the electronics business.

Startup in Swindon

Fischer was the technical one. He was a physics graduate who’d come out of Oxford University in 1971. Even then he had a mind to establish some sort of electronics company. It was an area he was keenly interested in. But he had been advised by a friend’s father, who happened to be an American patent lawyer, that he should go off and travel for a few years first before allowing himself to be tied down to running a business. Unlike the British parents Fischer met, his American advisor could appreciate not only the value of entrepreneurial ambition but also just how much work success would require.

Fischer took the advice to heart and spent the next couple of years in Africa, before returning the Britain to face the challenge of earning a living in 1970s Britain. Finding one led him to employment agency Manpower in Swindon and from there into an apprenticeship as an electrician.

And then he got a call from Mike O’Regan. This second Mike – "Mike O" to his pals – had studied economics at Cambridge. He hadn’t really enjoyed the subject and had only done it at all because, he says now, his careers guidance culminated in a choice of economics or law. Law, he feared, might involve too much Latin.

After university, O’Regan travelled in Spain for a time and then, like Fischer, returned home to try to earn a crust. He did temporary jobs, one of which had him teaching at a Sussex school for boys who had clear aptitude but were not realising their potential, typically because of disadvantaged backgrounds, behavioural issues, or ailments such as dyslexia.

Mike O enjoyed teaching, an occupation he had already experienced during a gap year spent in Uganda where he taught native kids English and maths. The son and grandson of teachers, O’Regan had an affinity for education, but it wasn’t, he then felt, where his future lay.

By chance the school brought him into contact with Mike Fischer’s brother, with whom he became friends. He got to know the Fischer family, and it was therefore obvious that when Mike Fischer came back from his travels and established himself in the electrical business, he should try to help out his brother’s pal, who was looking for something to do next.

Mike O met Mike F, who introduced him to Manpower. The agency set him up doing forklift driving and working as a fitter’s mate. Fischer put him up in his flat, and in the evenings they would pop out for a pint or two and ponder their futures.

In business

They soon discovered in each other a desire to work for themselves, says O’Regan. He wasn’t sure what he might want to do, but Fischer was clear: he wanted to do something that related to electronics. Mike O was fine with that, and the two agreed to go into business together.

The result was essentially Research Machines, established to build, naturally, machines for research. "RM" was a bit like "IBM", and the ambitious youngsters thought they might one day become the Big Blue of scientific equipment. This emphasis prompted the pair to leave Swindon for Oxford where Fischer had contacts in various colleges’ physics departments.

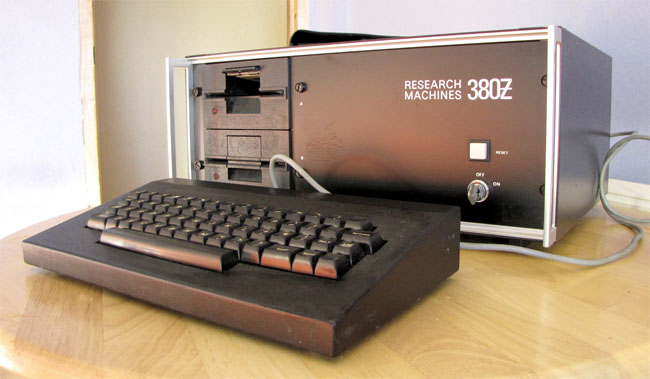

The 380Z in its classic configuration

Source: Paul Flo Williams

One of their first contracts, Fischer recalls, was to build an electroencephalograph machine to analyse rats’ sleeping brainwave patterns. O’Regan says that allowed them to formally establish Research Machines as a company, set up the requisite bank account and get a cheque book. It made their business legitimate. He also recalls an attempt to win a £10,000 instrumentation prize. His partner sought out contract work from his university contacts and this led to further projects with a scientific bent.

Fischer admits neither he nor O’Regan had any managerial experience - or, more to the point, much in the way of capital. Mike O remembers the pair working evenings as telephone operators to help make ends meet. “All the hours we put in on the first product meant we essentially made three pence an hour for it,” remembers Mike O. They managed to persuade their client to put up £600 in advance - and the bank to put up a similar sum.

To make Research Machines work, they realised, they needed more solid financing than that provided by the contract work. The upshot was the formation in 1974 of a Research Machines subsidiary to sell electronics components.

Sintel inside

“I noticed as an electronics guy that people who started with small ads in the electronics magazines selling components and kits seemed to survive... so we decided to get into the components and kits business to build up some knowledge and some money,” Fischer remembers.

They wanted to call it Sigma Electronics, but there were too many firms named Sigma already, so the new operation became Sintel. Recently established in the UK, Intel, then a much, much smaller company than it is now, grumbled and threatened, but the lads stuck with the name. Fischer was soon hacking together project kits, such as digital clocks, which Sintel could pitch through ads in magazines, and in articles written for the likes of Practical Electronics too.

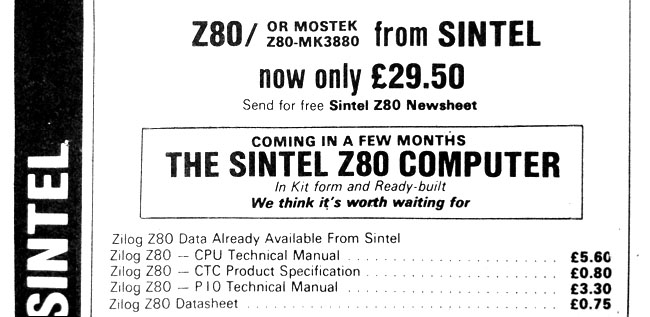

Sintel drops a hint: it’s working on a new computer

It was good experience for what was to come. They made mistakes, says O’Regan, for instance ordering far more National Semiconductor clock chips than they were then able to sell – they were able to cancel the order in the end – but running Sintel proved a straightforward endeavour, he says. While Fischer handled the technical stuff and headed the company, Mike O looked after sales, admin and the accounts – though not, he insists, because of his economics degree, which had given him no practical business skills at all.

“We were quite successful, by our standards, at selling kits,” says Fischer. “But I’d gone back to college to do a degree in physiology because I wanted to do something in medical research, so I wasn’t designing any more kits.” That prompted a discussion about the company’s future. “We decided we either had to become a commercial component supplier, like Maplin or a distributor, and build Sintel up as a business - or to manufacture something.”

The MITS Altair computer kit had come out in the US at the end of 1974, and this provided the inspiration for the RM founders’ next step. Designing a complete computer seemed only a small step up from designing clocks and such, so Fischer and O’Regan decided to follow the second of their two possible business plans and, as they put it, “make something”.

Educational emphasis

“We worked out we had enough money to buy parts for 200-250 computers so that’s what we did. We planned to sell 250 computers in the first year, and that’s what we did too,” Fischer remembers.

By now Sintel also had contacts in education, among them a couple of chaps in Reading who were computing advisors to Berkshire County Council and were at that point trying to build a computer that might be used in schools. They were buying their components from Sintel. It occurred to that it might be easier simply to get Sintel to design the whole machine for them.

That struck a chord with RM’s founders. Though the two Mikes realised that the future was clearly going to be in general-purpose computing, business machines in particular, they believed they couldn’t grow fast enough to become a long-term player in that part of the market. So eduction would be their focus, “a niche in which we could survive”, as Fischer puts it today. O’Regan’s UK teaching experience also gave him an insight into what kind of product schools might want.

Not that Mike and Mike were only considering a future in computers. Fischer recalls “plan after plan” drawn up to exit the computer business in due course and to focus more on, say, scientific applications, but the computer business grew and RM’s founders stuck with it.

Before then, RM’s first machine had to be created. The 380Z was designed by Fischer himself. His goal, he says, was “to bring out something that had the most advanced chips that money could buy and not worry about the cost because in a year the cost would have come down”. At the time, he was living in a house on Oxford’s Iffley Road, and Sintel was being run out of the property’s basement. Fischer created the 380Z in his bedroom, he and his wife moving back the bed every morning to make room for the trestle table upon which he would then continue to wire-wrap the components and motherboard.

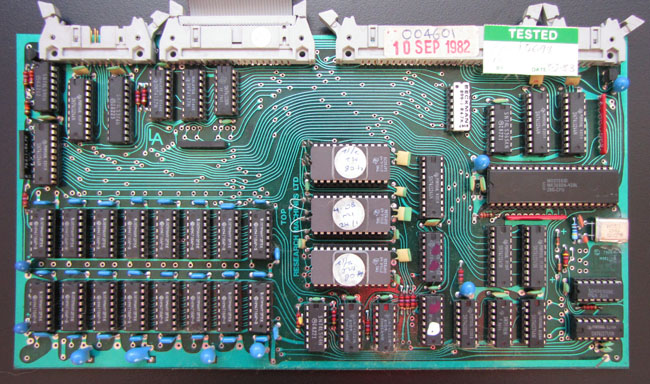

Fischer selected the Z80 processor because it was a more advanced version of the Intel 8080. The development of both chips was led by Frederico Faggin, first at Intel then at Zilog. The 8080 had been used in the Altair and by 1976/77 there was plenty of software available, among it Digital Research’s CP/M operating system. Fischer also liked the Z80’s ability to automatically refresh the computer’s DRAM. It required fewer ancillary chips than the 8080 did.

Dropping hints

“There were quite a lot of innovations to keep the component count down,” recalls Fischer. “We had quite a lot of inventions in terms of how you use chips to make a microcomputer which had we patented them at the time we’d have made quite a bit of money. But in those days no one did any patenting. Lots of the things we came up with were used in many other computers, including the IBM PC. In fact, we always paid a lower royalty to IBM than other manufacturers did on the grounds of not having to fight about patents. That was worth millions of pounds.”

Back in the mid-1970s, the electronics business was a cottage industry serving a small community of enthusiasts, many of whom met up in small clubs. Magazines like Practical Electronics and Electronics Today International (ETI) were written by and for devotees. Suppliers spoke directly to their customers through the ads they placed in those titles. The adverts were there to sell product, sure, but they were a combination of newsletter and message board too.

Most punters were expecting a board computer, not a cased one

Source: Paul Flo Williams

So it was no surprise that adverts placed by Sintel to appear in magazines published in May 1977 would, in addition to the long lists of available components available for sale, mention that the “Sintel Z80 computer” would be “coming in a few months... in kit form and ready built”.

“We think it’s worth waiting for,” the ad said enthusiastically.

ETI’s Gary Evans, an electronics journalist covering the new, emerging microcomputing scene in the mid-1970s, seemed impressed too, having seen an early prototype of the Sintel machine at the first European DIY Computer Conference, held in May 1977 at the Institution of Electrical Engineers’ HQ in London.

“Among the firms with their products on display were Sintel, who were showing a new Z80-based system which they hoped to market in kit form later this year,” Evans wrote. “Amongst other interesting features, this system has a very versatile VDU.”

Building the 380Z

Back in Oxford, work continued on the Sintel micro through the summer of 1977, primarily on its firmware. At the same time, in London, contractor Chris Shelton was designing the Nascom 1 for John Marshall’s Lynx Electronics. And gifted amateur Ian Williamson was hacking together old Sinclair calculator parts to produce a microprocessor programming kit that would inspire Science of Cambridge’s Chris Curry to launch the MK14 - Sinclair’s first computer product.

The 380Z firmware was primarily developed by David Small, who at that time was working as a neurology researcher but was discovering that he was far more interested in writing machine code programs for the DEC PDP-11 he had access to back at the lab. Fischer recruited him for the 380Z, for which he wrote the BIOS and on-screen monitor program resident in the 380Z’s 2KB of ROM.

The 380Z motherboard as it had become by 1979

Click for a larger image

Source: Paul Flo Williams

Small would soon join Research Machines full-time and become a shareholding company director. However, he and Fischer fell out in the early 1980s over his role in the company and he left to found High Level Hardware. In 1982, Small's firm announced the Orion, a 32-bit “high performance personal computer... designed primarily for the scientific community”. It was arguably Britain’s answer to the NeXT Cube, but it came two years in advance of Steve Jobs’ post-Apple offering.

Despite the break, Fischer still lauds Small’s coding skills: “He’s probably the best programmer I ever worked with. He’d pitch up with 4KB of machine code that he’d written on PDP, and we’d debug it and find maybe five bugs.”

Fischer himself specified the 380Z firmware and contributed code of his own: the cassette operating system, for instance. For reliability, he coded the machine to save two copies of the data, so if the first couldn’t be read, it could try to load the second. Another Oxford university find, Steve Cope, wrote the built-in full-screen text editor. Fischer’s physics department friend Bob Jarnot built an EPROM programmer to burn the firmware onto chips.

Teasing the release

Sintel was ready to announce its new machine in August 1977. “We will be offering two different packages,” the company’s ads said. “The first system, the Research Machines 380Z, will be available built and tested and also in kit form. This is a fully independent computer system used in conjunction with a television and cassette recorder.

“The second system, the Research Machines 280Z, will be available in uncased kit form, with a low-cost keyboard. The RM 280Z is designed to set a new low in computer systems pricing and it will bring a full computer system within reach of many more private computer enthusiasts.

“These computers are designed and manufactured in Oxford by Sintel’s parent company, Research Machines Limited, and will be sold through Sintel.”

Next came the promised spec: “The 380Z has a UHF output which plugs into the aerial socket of a completely unmodified domestic television. The TV screen will then display 24 rows of 40 characters... including upper and lower case.” The character set was the 128-character ISO 7 standard; the 380Z also used the standard Kansas City 300bps cassette system.

“The computer is housed in an instrument case with power supply, and a lot of room for expansion,” said Sintel, and added that the machine’s base 4KB of Ram could be upgraded to 32KB “without adding any memory PCBs”. The 380Z would come with a “keyboard in a separate case”.

The casing, incidentally, was simply what RM could get hold of. Originally released in white and blue, it used an off-the-shelf instrument housing from Vero, a maker of components. “We had to add lots of bits of perspex with double-sided tape to stop the sides bending!” recalls Fischer. So it was soon replaced with a custom version of another Vero casing, tweaked to add the familiar handles and key lock. The idea of putting a lock on the front of the box was “probably pinched off a PDP-8,” Fischer reckons.

Ready to launch

At this stage, Sintel wasn’t say how much the machine would cost, but few readers would have assumed it to be cheap. Today, 32KB of memory doesn’t sound very much at all, but the upgrade would have added many hundreds of pounds to the price of the base machine, and even 4KB wasn’t considered inexpensive.

The Nascom 1, for instance, had just 2KB, half of which was used as video memory. The MK14 had just 256 bytes of RAM. Memory was expensive, and it was clear that the 380Z would be too. To cater for punters on low budgets, Sintel also announced the 280Z, which, it promised, would “cost somewhere between the price of a manufacturer’s Development Kit using hex display and keyboard, and a fully cased computer system”. In short, it was the 380Z’s VDU board and motherboard but with less memory, no keyboard and no power supply.

Advertising the 380Z

The following month, Sintel talked up the “very versatile VDU” that ETI’s Gary Evans had enthused about after seeing the prototype: “Each character position on the VDU is written in to and can be read by the CPU as a memory location. This means the VDU is software controlled and can be programmed to operate in any mode, including page mode, scrolled, immediate mode editing, or fully addressable cursor. The whole VDU can be filled with new data in less than 10ms! Screen refreshing does not use any of the Z80’s time.”

In October 1977, Sintel began advertising its new machines. A 380Z with 16KB of RAM, 2KB of ROM, a 4MHz Z80A processor, all cased and supplied with a plug-in “cased keyboard... a 53-key robust keyboard with ASR-33 layout” would set you back £1,063 – the equivalent of £5,590 in today’s money, based on changes in the retail price index over the past 35 years.

The 280Z was cheaper: £499 – equivalent to £2,620 now – for a “partly assembled” kit with 2KB of RAM, 1KB of ROM, the same 4MHz Z80A as the 380Z but no keyboard.

All the prices I’ve mentioned were less eight per cent VAT, of course.

For schools and colleges

No wonder the Nascom 1, which was just about to make its debut, would win the hearts and minds of the new computer enthusiasts - it cost less than half the price of the 280Z, let alone the 380Z. But of course, Fischer and O’Regan had set their sights higher than the hobbyist market John Marshall was out to attract.

Examining a Nascom 1 kit, they couldn’t figure out how Marshall could but sell his machine at a loss, thanks to the cost of the components alone. Sintel’s bosses knew how to buy components, but perhaps they lacked Marshall’s ability to cut deals and to find low-cost surplus supplies overseas.

At launch, Sintel said the 380Z and 280Z would ship in four to six weeks’ time, and by all accounts the first machines did indeed go out in December 1977, albeit in very small numbers. Two months later, in February 1978, the very first issue of Personal Computer World magazine reported that the 380Z was only now about to go on sale. Early education customers got their machines first.

Inside the famous case

Source: Paul Flo Williams

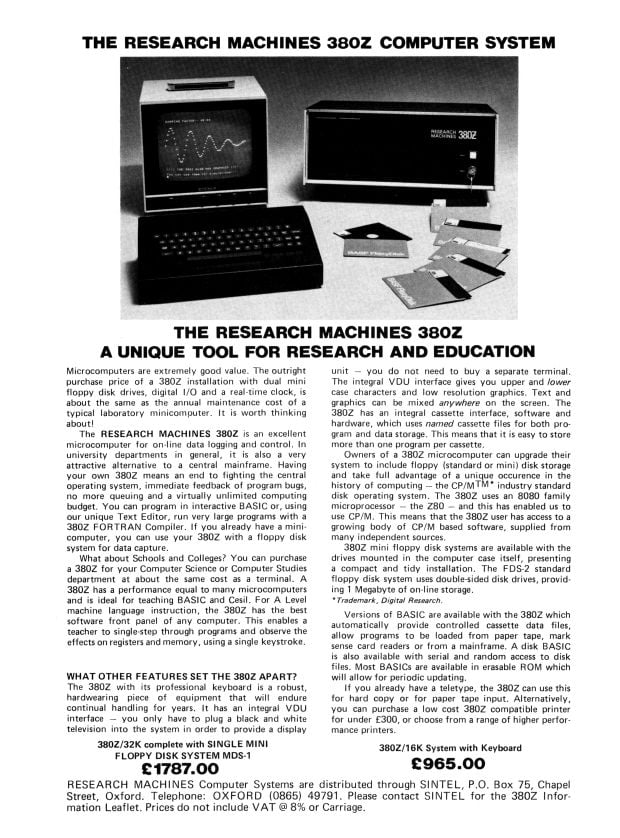

PCW didn’t review the 380Z until April. Such was the volatility in Ram prices, that the 16KB 380Z was now quoted at £1038 and the 4KB version at £848. Cheaper than mere months before, but still out of reach of all but the most well-heeled micro enthusiast. By October 1978, when Research Machines introduced a 32KB 380Z with a built-in 5.25-inch floppy drive – for £1,787 – the 16KB cassette-only model was retailing for £965.

“Our system is sold for the most part to the education and scientific markets,” an unnamed Research Machines spokesman was quoted as saying by Practical Computing reviewer Martin Collins in the magazine’s December 1978 issue.

“I asked RML if I could take home the system for the weekend if I promised to keep the children from it. ‘Don’t worry about the children,’ they said, ‘it’s very tough. They will do no harm’.”

Quality build

Collins was impressed to find that that was indeed the case. And if he found the machine to be aimed at experienced users rather than newbies - the Basic language documentation, for instance, was “sketchy” - he nonetheless felt able to conclude that the 380Z “is one of the best micro systems we have examined and it is British... It is more expensive than some competitive [sic] systems but the extra cost is justified by the high standard of manufacture”.

Indeed, RM made a virtue of this. Even the cassette players it supplied were tested and, if necessary, the heads adjusted to ensure buyers got as much error-free loading and saving as possible. “We tested everything,” says Fischer. No wonder the 380Z was expensive. Today O’Regan admits it might have been over-engineered.

“Sinclair, whom I admired in many ways, did cut corners enormously in order to get his vision in hobbyists’ hands. We could never do that - it wasn’t our style,” adds Fischer. “We had a strong ethos of selling things that worked and were reliable.

“We were trying to sell the 380Z as a machine schools could use to get on with computing, not to fiddle around with. It was a workhorse machine. When we added disk drives, we spent a lot of time going around the world trying to find drives that were reliable. We ended up using Japanese floppy drives - we were the first to do so - and again we tested those like crazy.

“To begin with we used German disk drives from BASF and they were better than the American ones but they still failed with monotonous regularity.”

The rubber drive belt also had a knack of slipping off. So the firmware was tweaked to support also booting off a disk in the B drive and not just the default A drive, in case the A drive failed.

This kind of pragmatism led to the development of RM’s networking technology. Schools might not be able to afford a floppy drive per machine, let alone more than one hard disk, so RM equipped its keyboard units with Zilog serial communications chips and processor cards to allow them to operate independently but still tap into a single 380Z as a file store. That’s what the first, black-clad 480Z was: a 380Z in a big keyboard case and geared to tap into a connected 380Z file-store.

Computer literacy

That meant that the 480Z was considerably cheaper than the 380Z: around £550 to the £1,000-plus that RM wanted for the older, but much more expandable machine. Despite the 380Z’s high price, schools prized its scope for expansion, says O’Regan.

Designed with an eye to the declining prices of chips, by 1979 the 380Z was arguably the best British micro available. It was now cost-effective to make, but had been around long enough to have the bugs ironed out. At this point, the ZX series wasn’t even a glint in Clive Sinclair’s eye. The 380Z was being installed in schools and colleges when Acorn was still only selling Eurocard-based board machines for industrial use. It’s ironic, then, that it is Acorn, rather than Research Machines, that is more fondly remembered as the UK’s prime seller of computers for schools.

Round back, no shortage of portage

Click for larger image

Source: Paul Flo Williams

With the arrival of the 380Z, RM’s turnover trebled, O’Regan recalls, from around £100,000 to £300,000. The next year it passed the million-pound mark and continued to increase: from £3m to £5m to £8m. Over that period RM shipped in the region of 10,000-15,000 machines, almost entirely to Britain’s 5000-odd secondary schools and higher education institutions.

RM, of course, was focused specifically on the education market, and through the late 1970s and early 1980s it established a strong presence in schools. Fischer points to Bill Tagg, an early supporter of the 380Z who was not only in charge of specifying computers for Hertfordshire schools but also an influential voice in the sector. He was an early buyer, who backed Research Machines when it was essentially little more than a start-up.

Ditto Derek Esterson, who acquired computers for schools controlled by the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) quango and who backed the 380Z early on. “Britain led the way, numerically and in every other way, in computers in education for a very long time,” says Fischer. “If there was one person who should have got a knighthood for making sure more children came out of school computer literate in the 1980s it was Derek Esterson.”

The impact of the BBC

Even today, it’s clear that the BBC’s decision to enter the microcomputer market annoys Mike Fischer almost as much as it famously angered Clive Sinclair. Of course, the BBC might have worked with Research Machines instead of Acorn. Certainly, RM was one of the seven British manufacturers the Corporation approached about a possible microcomputer partnership.

But Fischer realised that a machine based on the BBC’s hardware and software specifications and intended to be sold at the price the Corporation wanted could not be produced reliably within the launch timescale the broadcaster was set upon. RM chose not to pursue the BBC contract as it stood. It told the BBC it could produce the machine the Corporation wanted, but it would take twice as long to bring to market and cost twice as much.

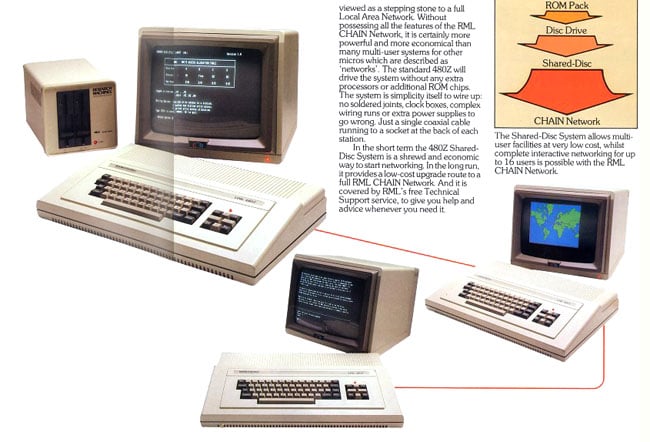

The first incarnation of RM’s Link 480Z

Fischer was unsurprised, then, when Acorn’s BBC Micro was launched late, took far longer than planned to reach everyone who’d ordered one, and ended up costing more than forecast.

Yet the BBC’s imprimatur gave the Acorn machine a particular boost: it made the machine very attractive to schools. RM’s relatively high prices didn’t help, of course, and it suffered mightily from the competition it was given by the Corporation’s machine. “It almost put us out of business,” says Fischer today. “We had some very tough times.”

The 480Z was launched in 1982, but the 380Z continued to be made available until 1985. RM would stay focused on education despite taking a pummelling from Acorn and even after shifting from its Z80-based range to the Intel-based Nimbus family of PC compatibles in the mid-1980s.

“All people could really do in schools was give kids a chance: for the techies to write a bit of machine code and Basic - people like us - and for the vast majority of students to be introduced to the concept of word processors, spreadsheets and databases,” says Fischer.

Beyond the 380Z

“And so right from the beginning our machines were the ones that ran commercial software. Britain was the first and only country for many years where the standard software in schools was Microsoft Office.”

Despite the arrival of the BBC in schools and the explosion of interest in computing in the early 1980s, Fischer and O’Regan never seriously considered extending their reach beyond education and into the home computing market.

“We were different in that we sold direct and we wanted to continue doing that - that was our model,” says O’Regan. “But it meant that our street presence was zero.

RM’s revised 480Z design - and its central storage unit

“People from outside the company were saying this is a lost opportunity, implying that we were failing in some way because our the home computer companies were growing by 10-20 times and we were growing ‘only’ two to three times in a year. The home machines were a potential threat to our position in education, but we kept doing what we wanted to do.”

The proof that this was the right approach? By the end of the 1980s, Research Machines was still in business when so many of its one-time rivals had gone to the wall.

At the end of the decade, the company prepared to float on the London Stock Exchange. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait put paid to that, but two years later it made a second attempt, and this time came to market as RM Plc.

Still in business, still in education

Today, RM is smaller than it was at its peak in the late 1990s, but it continues to sell branded PCs to schools, the current kit rebadged notebooks imported from Asia and desktops assembled from off-the-shelf parts rather than the home-grown machines of old. It’s also an Apple dealership.

Mike O’Regan remained an executive director of RM until 1992, the time of the flotation, when he became a non-executive director, a position he held until 2004. He has never lost his love of education and teaching. In 1988 he founded the Hamilton Trust, a charity that devises educational programmes to help kids from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, originally those living in the estates bordering Oxford’s Ring Road.

The two Mikes today: O’Regan (left) and Fischer (right)

Those early days in Oxford running a startup gave O’Regan a powerful interest in the process of running small businesses, and his latter day educational work also focuses on encouraging and aiding would-be entrepreneurs as they take their first steps in business.

He has an honorary degree from Oxford Brookes University, and also holds an honorary degree from the Open University, awarded in 2002.

So does Mike Fischer, who also continued to be non-executive director of RM until the major reorganisation of 2004, though he remains the company’s President, a lifetime appointment.

His focus these days is on the medical research that had been close to his heart since the mid-1970s. In 2000, he was awarded a CBE for his services to educational computing - Mike O’Regan has an OBE. Like O’Regan, Fischer also runs an educational charity, the Fischer Family Trust, which is focused on crunching numbers for the benefit of schools and educators. ®

The author would like to thank Mike Fischer and Mike O’Regan for their generous help and assistance in the research of this history. Thanks too go to Paul Flo Williams for kindly photographing his 380Z.