Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/11/11/feature_how_doctor_who_plundered_sf_film_and_literature/

Doctor Who nicked my plot and all I got was a mention in this lousy feature

How writers plundered sci-fi, literature, films and more

Posted in Personal Tech, 11th November 2013 10:00 GMT

Doctor Who @ 50 There’s no question: blocked Doctor Who writers and Script Editors - or Story Editors as they were in the very early days - frequently turned to movies and books for inspiration. They regularly resorted to, ahem, "borrowing" plots and ideas from famous flicks and notorious novels for the basis for their Doctor Who stories.

Sherlock Holmes and the Butcher of Brisbane: ”Perhaps you’ve read my monograph on the many varieties of Chinese bath soap?”

Source: BBC

Heck, the show itself was brought into being on the back of H G Wells’ The Time Machine and the works of Jules Verne, and later contributors were no less keen to plunder the lands of science fiction, literature and mythology in order to meet script deadlines.

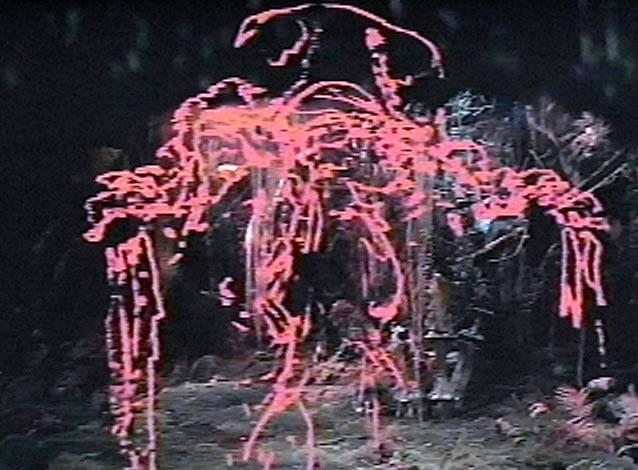

Often the designers and special effects guys went along too, taking visual cues from the source. Consider the invisible-then-red-outline anti-matter beast that attacks Tom Baker in 1974’s Planet of Evil in almost direct imitation of the invisible-then-red-outline Monster of the Id that attacks Leslie Nielsen in 1956 film Forbidden Planet. The villain in both is an unhinged scientist; the protagonists in both cases are crews of military starships. Planet of Evil, written by Louis Marks, lacks the vast city of the Krell but makes up for it with one of the best-realised alien jungle sets in television sci-fi history.

And all that’s before you remember the other half of the story is a futuristic take on The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, with Freddie Jaeger’s Professor Sorenson mutating in a moment from tired anti-matter boffin to the shaggy beast within. A nice twist: here the Prof takes an archetypical smoking medicinal draught to prevent the transmogrification rather than trigger it.

From the Forbidden Planet of Evil: a red, semi-visible monster

Source: BBC

In the years before home video players, it was easier to get away with this kind of thing, of course. But now writers’ plundering is exposed for all to see. Here, then, are some of the more egregious examples.

Writer Robert Holmes was perhaps the most shameless of Doctor Who’s rip-off merchants. Many of his stories appear in our list, and a few of the others were commissioned and heavily rewritten by him during his time as the programme’s Script Editor in the mid-1970s. That said, it’s surely no coincidence that Holmes was also one of the best Doctor Who writers to contribute to the show’s initial 25-year run and possibly, some would argue, the best writer the classic series ever had.

Holmes’ secret was to grab the essence of his source material but cleverly wrap it enough new stuff that the story that followed felt totally Doctor Who. Yes, you might recognise a character, a situation, a milieu or an entire genre from one of his stories, but the revelation wouldn’t kill the adventure stone dead. Rather than making it suddenly impossible for the viewer to willingly suspend his or her disbelief, Holmes’ borrowings and the way they were woven into the script actually made the story more enjoyable.

‘The World shall hear from me again. Not Fu Manchu but mad magician Li-Hsen Chang. And Mr Sin

Source: BBC

Take The Talons of Weng-Chiang, Holmes’ distillation of so much cod Victoriana. It’s primarily flavoured with allusions to Sherlock Holmes, though he character as it existed in the popular imagination rather than Conan Doyle’s creation. Likewise popular culture impressions of Jack the Ripper and the fog-bound pea-souper London of Ripper mythology. There’s a hint of Edgar Allen Poe in there too and a soupçon of Bram Stoker. There’s even a comical nod to popular 1970s variety show The Good Old Days.

And not just Leonard Sachs, but Sax Rohmer. You might detect in Talons a whiff of Rohmer’s Chinese fiend Fu Manchu, who surely inspired Robert Holmes’ Oriental magician Li-Hsen Chang and his gang of Chinese martial artist henchmench, the Tong of the Black Scorpion. Rohmer’s tales derive from the early 20th Century rather than the nineteenth. So does villain Magnus Greel’s subterranean lair. Located beneath a theatre and served with sewer highways and byways, it comes straight out of Gaston Leroux’s 1909 novel The Phantom of the Opera.

A more recent steal: the 1974 movie version of Ian Fleming’s The Man with the Golden Gun features a giant laser gun and a fight with a midget, here represented by the Dragon Ray Gun and Mr Sin, the ”pig-brained Peking Homonculous” - played, as all characters of diminutive stature were back then, by Deep Roy, better known to cinema goers as Princess Aura’s pet in Flash Gordon and every single Umpa Lumpas in Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The Linx effect: Sontaran kidnaps Earth boffins... just like Exeter the Metallunian does in This Island Earth

Source: BBC

Holmes made a habit of this kind of thing. The Time Warrior, Holmes’ story that introduced the Doctor Who audience to the Sontarans, then a harsher, more brutal race of clone warriors than the comedy martinets of today, lifts one of its central premises - alien kidnaps Earth scientists to make use of their brain power - from 1957 sci-fi flick This Island Earth, though Holmes made the abduction happen through time rather than across space, and passes water on the source material from a great height with his trademark deadpan dialogue: “So you have a primary and secondary reproductive system. It is inefficient. You should change it.”

What the Dickens

The Holmes co-written Trial of a Time Lord takes its structure straight from Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The already mentioned Planet of Evil, though written by Louis Marks, had a large input from Holmes, and Holmes’ work on Terrance Dicks’ script The Brain of Morbius prompted the commissioned writer to demand a pseudonym appear on screen instead of his own, so far had Holmes’ rewrites shifted the story away from the original. Oh, and the name ‘Morbius’ comes (again) from Forbidden Planet of course.

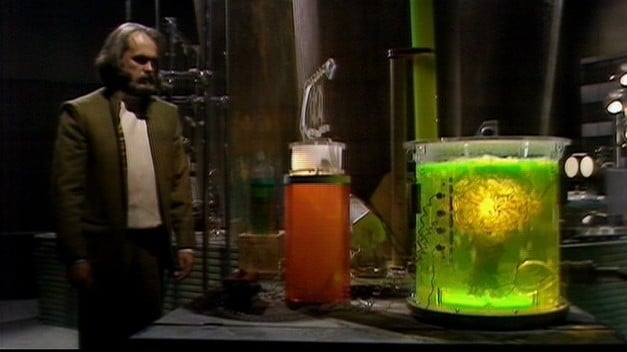

Donovan’s Brain of Morbius

Source: BBC

Dicks’ notion was of a robot struggling and failing to make a new frame for his (almost) disembodied master: not enough spare parts, insufficient understanding of the finer points of human anatomy - none of the Terminator’s “detailed files” here. Holmes, however, decided he wanted the story to be the very Frankenstein rip-off Dicks was so keen to avoid. Frankenstein of the 1930s Universal Pictures films, that is, not Mary Shelley’s gothic original. Philip Madoc’s excellent Mehendri Solon has far more in common with Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein than Victor F. And Colin Fay’s Condo is pure Fritz, the character everyone assumes is called ‘Igor’. The story channels Donovan’s Brain too, of course.

Another source, though whether introduced by Holmes or Dicks isn’t known, is H Rider Haggard’s 1886 novel She, in which a sisterhood guarding the secret of immortality, which turns out to be a flame of burning volcanic gas - which is exactly what the Sisterhood of Karn are all about. And there’s no shortage of movie prototypes for the brain-in-a-jar Morbius, of course.

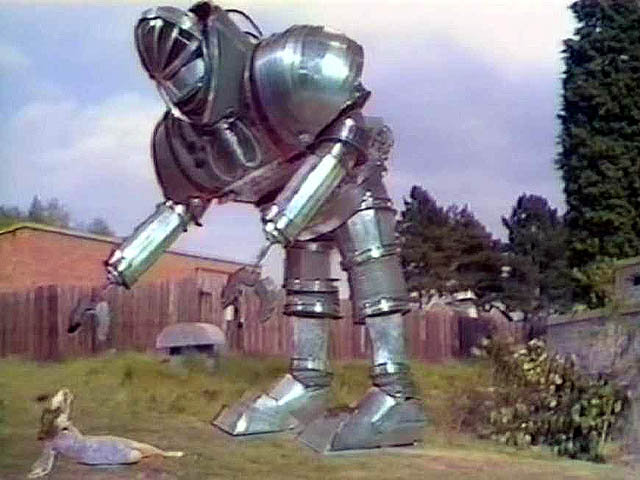

Terrance Dicks might complain about Holmes’ ‘homages’, but he was no stranger to borrowing ideas from great works himself. The case for the prosecution rests on Robot, Tom Baker’s debut story in which a huge athropomorphic machine stumbles around with the Doctor’s journalist companion, Sarah-Jane Smith, in his claws. Experimental Robot K-1 isn’t as sympatico with Sarah as giant ape King Kong is of Fay Wray’s Ann Darrow, but it’s not hard to see how the 1933 movie inspired the 1975 script and some its imagery.

King Kong K-1 and Sarah Fay Wray Jane

Source: BBC

Dicks wrote Robot while he was wrapping up his tenure as the programme’s Script Editor. One of his first editing jobs for then new Doctor Jon Pertwee was Doctor Who and the Silurians, written by Who stalwart Malcolm Hulke and which clearly channels Conan Doyle’s The Lost World and its still-living relics of the Earth’s saurian past into early 1970s Britain and a government-sponsored scheme to drive the nation forward with lashings of low-cost electricity.

Dicks would go on to oversee the Daemons, a story written by his boss, Barry Letts, and which mercilessly plunders Dennis Wheatley stories and the entire canon of British magical and occult thrillers in which diabolic forces manifest themselves in England’s green and pleaseant - and very Middle Class - land. Well, it beats all that guff about colonialism, ecology, miners’ strikes and joining the European Union. Oh and prison reform, though that story, The Mind of Evil, in which The Master builds a telepathic gadget to subdue difficult convicts owes much to Star Trek episode Dagger of the Mind.

In the 1980’s Dicks’ State of Decay raided almost every classic vampire work of the 18th and 19th Centuries, from the black comedy of Varney the Vampyre to the Lesbicious overtones of Joseph Sheridan LeFanu’s novelette, Carmilla: one of the Three Who Rule is called Camilla and she takes a close interest in Time Lady Romana. It’s a cute story, but Dicks’ Horror of Fang Rock is better, though again thanks in part to Robert Holmes’ adjustments.

Fangs for the memory: State of Decay takes a big bite out of the gothic vampire meme

Source: BBC

Other writers could be no less keen to seek out inspiration from sci-fi. John Lucarotti’s script The Ark in Space was later heavilly rewritten by, yes, Robert Holmes. Holmes, however, left in Lucarotti’s notion of aliens penetrating a space station to impregnate sleeping humans. That’s a notion with a very particular SF heritage: AE Van Vogt’s short story Rhapsody in Scarlet, which was later integrated into his novel Voyage of the Space Beagle. In the early 1980s, Van Vogt successfully sued the creators of Alien for pinching his idea. He seems to have never been troubled by The Ark in Space, which, despite its terrible 1970s flared trousers and flared sideburns, is actually rather good.

You can’t quite say the same for Bob Baker and Dave Martin’s The Invisible Enemy, which takes the central premise of the 1966 big-budget film Fantastic Voyage and miniaturises it for injection into the much tinier world of British TV. Doctor Who in the late 1970s lacked the cash to realise the complext interior bioscape of human blood vessels, organs and the lymphatic system, so we had to make do with the alien - and thus unrecognisable - brain of the Doctor. There was no money for a submarine, either. But there is a compensation: Loiuse Jameson is far more fetching in her savage leathers than Raquel Welch in rubber scuba gear.

Alas, the BBC couldn’t afford to shoot Doctor Who in Antarctica - or anywhere else with plenty of real snow - so a jabolite and soap foam-filled quarry had stand in for the South Pole during episodes one and two of Robert Banks Stewart’s 1976 The Seeds of Doom, which is really just The Thing From Another World - hostile vegetable lifeform buried for millenia in the ice, anyone? - given the Doctor Who treatment. The fully formed Krynoid’s attack on the Harrison Chase’s country gaff is surely a steal from The Quatermass Experiment and mutated spaceman Victor Carroon’s dissolution of Westminster Abbey?

A thing from another world: one of the Seeds of Doom

Source: BBC

Speaking of Quatermass, where else did writer Chris Boucher get his notion, used in the excellent Image of the Fendahl, of a once deeply buried skull revealing the real and ineffably ancient origins of the human race other than Quatermass and the Pit? Still, you can forgive the writer of The Face of Evil and The Robots of the Death anything. All three stories are Who gems.

Das Reboot

There are many more examples of 1970s and 1980s Who plots ported from others’ source code: David Fisher’s Androids of Tara is Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda; Underworld, The Horns of Nimon and The Time Monster borrow great wedges of Greek myth; Chris Bidmead’s Castrovalva wouldn’t be what it is without the art of MC Escher; Peter Grimwade’s Mawdryn Undead relies on the Flying Dutchman story; Glen McCoy’s atrocious Timelash namechecks HG Wells and many of his works. But these are deliberate references - the audience is expected to spot the connections. And then, of course, you get a story like Christopher Bailey’s Kinda which just pelts you with references, literary, filmic and religious. And still manages, rubber snake aside, to be one of Doctor Who’s very few and finest attempts at really intelligent SF. Steve Gallagher’s splendid pseudonymous story Warriors’ Gate is another.

Kinda: great sci-fi... but don’t mention the rubber snake, OK?

Source: BBC

In later years, Doctor Who’s production teams would increasingly comprise writers and editors who had grown up with British TV in the 1960s and 1970s rather than popular potboilers and black-and-white movie thrillers. Inspiration from movies become more tangential and, oddly, as a result more disappointing.

I can still recall the groans of the audience I was a part of as the watched Sylvester McCoy story Dragonfire for the first time with its woefully sub-H R Giger xenomorph and a team of space marines fearfully using their motion trackers to monitor the invisible approach of the deadly aliens [surely ‘two pickelhuber-helmeted goons with a red flashing light attached to their pathetic, plastic toy-like guns’ - Ed].

The design of the Ergon in 1983’s Arc of Infinity channels Giger’s Alien too, as does the Vanir armour in Terminus with the Sutton Hoo helmet topping it to reflect the story’s Norse mythology references, Old Norse and Germanic paganism being close enough for the latter to reflect the former.

‘I have HR Giger’s lawyer on the phone...’

Source: BBC

Stephen Wyatt’s Paradise Towers script borrows heavily from J G Ballard’s High Rise, a sinister tale of locked-in residents running amuck. It could have been brilliant, as per the dystopian novel, but the whole structure collapses as comedy, both intentional - Joseph Kesselring’s 1939 funny play Arsenic and Old Lace was an inspiration too - and unintentional, dissolves the foundations.

By the time of Doctor Who’s 2005 revival, writers were being inspired by the series itself, and its many post-cancellation spin-off works. Rebooter Russell T Davies even commissioned writers Rob Shearman, Paul Cornell and Stephen Moffatt to regenerate stories they’d already written for, respectively, Big Finish audio productions, Virgin Books and the Doctor Who Annual. Yes, Dalek; Human Nature and The Family of Blood; and Blink all had lives before they were ported to the small screen. When Moffatt took over control of the programme from Davies, he commissioned Gareth Roberts’ to turn the latter’s Doctor Who Magazine one-off comic strip The Lodger into a story for the 2010 season.

Pop will, as they say, eat itself.

Douglas Adams raided his contributions to City of Death for Dirk Gently material

Source: BBC

Incidentally, it works the other way too. Hitch-hikers’ Guide to the Galaxy creator Douglas Adams was once a Doctor Who Script Editor and writer. Many years later, he travelled in the opposite directection to plunder his Who scripts The City of Death and the unfinished, unbroadcast Shada for material to include in his 1987 novel Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency.

Today’s Doctor Who is no less inspired by other media than the ‘classic series’ was, though writers now seem keener to be more subtle in their borrowings, taking broad ideas and wrapping new stories around them rather than penning ‘Doctor Who does...’ episodes. A case in point is the penultimate episode of 2005 season, Russell T Davies’ Bad Wolf and its game shows played to fatal extremes, an idea surely motivated by the 1977 Judge Dredd story ‘You Bet Your Life’.

Indeed, Dredd’s informer, Max Normal, was caricatured in Davies’ 2007 story Gridlock, which also features virtual newscaster Sally Calypso, a derivative of virtual newscaster Swifty Frisco from 2000AD’s first The Ballad of Halo Jones series. And I have a sneaking suspicion Davies’ 2006 story Tooth and Claw owes much to Games Workshop’s RPG Golden Heroes and its add-on scenario pack Queen Victoria and the Holy Grail.

Gridlock in Mega-City One: Max Normal, the Pinstripe Freak, observes the Doctor’s sonic vandalism. Will he tell Dredd?

Source: BBC

Meanwhile, Stephen Greenhorn’s 2007 story, The Lazarus Experiment sends The Quatermass Experiment through a teleporter into which has also slipped The Fly. Chris Chibnall’s 42, which followed The Lazarus Experiment in broadcast order, channels 24 into sci-fi - or at least the notion of a countdown through the series/story. The aerial ghosts of The Unquiet Dead surely owe much to the flying phantoms haunting the climax of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The 2007 Christmas Special, Voyage of the Damned</i>, is The Poseidon Adventure. With Kylie.

Airing just before that, we have The Last of the Time Lords, the second episode of Davies’ Master reboot and which sees the Doctor light the villain’s funeral pyre with a burning torch just the way Luke Skywalker sets Darth Vador’s body a-burning, but the Master’s essence is squirted into a ring that is later carried away by a mysterious hand. Don’t tell me Davies has never seen the 1980s remake of Flash Gordon...

Finally, let’s not forget the Doctor and the Ponds’ scheme to record appearances of the Silence in biro on various parts of their anatomies bears an amazing resemblance to the ballpoint pen recording scheme employed by Guy Pearce in Christopher Nolan’s first feature, Memento. ®