Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/11/05/ten_top_classic_doctor_who_stories/

Ten top stories from Classic Doctor Who

The DVDs to watch to celebrate 50 years of Tardis travel

Posted in Personal Tech, 5th November 2013 15:00 GMT

Doctor Who @ 50 ‘Classic’ is a word that was already worn out back in the mid-1980s when fanzine editors and contributors couldn’t help themselves attach it to any Doctor Who story they were particularly keen on, whatever its merits. Thirty-odd years on, the word is no less overused, but the release of stories on VHS and, later, DVD has helped rub some of the rose-tinting off fans’ spectacle lens.

Three decades ago, we only had our memories and write-ups in Doctor Who Monthly to look back on. Now we can sit down and watch the stories we once thought were among the best the show’s various production teams had created.

Of course, we’re older now too, and most of us have more robust, adult critical facilities. Those of us who still appreciate the Classic Who era - that word again - can look beyond the poorly constructed sets, the OTT costumes and hyperbolic dialogue to the story the creators were trying to tell. Doctor Who in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s will never escape the technological limitations of television at the time, but it is possible to look beyond them.

Here, then, are the ten Doctor Who stories, presented in alphabetical order, we think best showed the heights the programme was capable of reaching, despite low budgets, tight shooting schedules and no computer graphics to paint out the glitches. These are stories that hook you in with their ideas, their characters and, in some instances, even their presentation - or in spite of it.

If the 50th anniversary prompts feelings of nostalgia, you could do a lot worse than add these to your video collection.

The Ark in Space

Years before Alien, a ghastly creature slips aboard a sleeping space station and inserts an embryo into one of the human crew held in suspended animation. Time passes and the Doctor arrives just in time to deal with the larva, though not before it infects one of the now waking station personnel. The future of the human race is in the Doctor’s hands - can he defeat the insect menace and return the sleepers to their home?

We should get the bad stuff out of the way first: the flared trousers and the ridiculous sideburns; the green bubblewrap ‘infection’ encasing Noah’s hand; the way the otherwise well-realised Wirrn insects don’t actually walk on their legs; the way crew leaders Noah and Vira speak a kind of 23rd Century dialect, but crew member Rogin sound like a 20th Century wide-boy; the stupid-looking guns; would 23rd Century humanity really build the Ark out of expanded polystyrene?; why an alien that can subvert human cells by touch needs to bother with all that impregnation business; and, and, and...

A bug hunt or a stand-up fight?

Source: BBC

None of which really matters because The Ark in Space - conceived by John Lucarotti whose script was then largely rewritten by Robert Holmes - is a cracking yarn. The Wirrn are a genuinely creepy monster and a race that, for once, is not trying to conquer the universe but merely obeying the rules of its own biology. The characters are engaging, and for all the naffness of Noah’s transforming appendage, his fight to retain his humanity while being Wirrn-ised is affecting and paves the way for his final act of self-sacrifice.

What we have here is an exemplar of how easy it was for Classic Who production teams to over-reach themselves. Realising the Wirrn and the transmogrification of human to insect were never going to be easy to do convincingly on Doctor Who budgets and timescales, but by golly they tried anyway. And it’s a testament to the writing and acting that they get away with it. You snigger at the flaws, sure, but you also enjoy the story.

The Caves of Androzani

Script Editor Chris Bidmead’s concept of the fifth Doctor was of an old man trapped inside a young man’s body: physically able but lacking the drive to make use of it. But in this, the fifth Doctor’s final story, he at last gets to make use of that physicality as he sacrifices his own life to save that of his companion, Peri.

Desperation drives the Doctor to the edge of madness. The clue is in the title: ‘andro’ is Greek for ‘man’, ‘zani’ is ‘zany’, a word which originally meant ‘clown’ but later became synonymous with ‘mad’.

Mad men: the Doctor and Sharaz Jek (right) engage in verbal fencing while Peri (left) looks on

Source: BBC

The Doctor, of course, has the inner strength to retain his sanity - he’s striving to save Peri, not to seek revenge. Not so the piece’s nominal villain, Sharaz Jek, who is driven round the bend and then some by the callous actions taken by the story’s real baddy, Morgus, his former business partner who has become rich by ruthlessly screwing over absolutely everyone he can: workers at his mines, his mercenary force, even the body politic of his homeworld.

Everyone here is truly screwed up. The population are in thrall to the drug Spectrox, which massively extends human life, to the exclusion of morality. Morgus is entirely solipsistic, as is Jek’s desire for revenge against him. Stotz’s mercenaries are, by definition, fighting for money not a cause, and even the real army is fighting a war of cynical political expediency.

The Doctor and Peri naturally stumble right into the middle of it all. Peri literally falls into a nest of the lethal pre-refined Spectrox, an accident which sets in motion every event that then takes place throughout the remainder of the story’s four episodes. It’s genius plotting on writer Robert Holmes’ part and it leads to a literally explosive climax - ably directed by Graeme Harper - as geophysical forces blast Androzani Minor and the Doctor undergoes an tumultuous regeneration.

The City of Death

Picture a man reaching up to grasp the skin of his face... and pulling the flesh away to reveal a single widely open eye staring out of a mass of bright green seaweed. Yeah, on TV in 1979 it wasn’t how you picture it now, but that’s the defining image of the David Fisher written, Douglas Adams edited City of Death.

The being in question is Scaroth, last of the Jaggaroth, friend of the Buggeroff and fragmented temporally by his exploding starship. His solution: work with his many separate selves - they’re connected telepathically, kind of - to evolve the human race to the point at which it can develop time travel. Then he can go back and prevent the explosion. Easy.

Fighting for the survival of a species: Jaggaroth vs humanity

Source: BBC

Except the Doctor figures out the explosion is the trigger that starts the human race by causing the basic building blocks of life to form and kick-start evolution.

It’s a great plot, driven along by Adams’ humour - he was working on the Hitch-hiker’s Guide radio series around this time - and its Parisian setting, for once shot for real rather than in mock-up. The Doctor and Romana have a laugh; their sidekick, Duggan, gets to throw the most important punch in history; the Mona Lisa gets stolen and then found half a dozen times over; and there’s even a cameo from John Cleese.

Doctor Who had become downright daft during the late 1970s. City of Death gets a bit silly too, but it’s all done with such joie de vivre, it works.

The Crusade

Historical stories were a key part of Doctor Who’s early years and the product of the production team’s brief to make use of the Tardis’ ability to travel in time as well as space. Of course, it quickly became clear that kids really wanted the sci-fi stuff not the often dry purely historical episodes.

Over time, Doctor Who production teams attempted to make the historicals more interesting, most commonly by doing them as comedies, but eventually they got knocked on the head after Patrick Troughton story The Highlanders in 1967. 1982’s Black Orchid was a once only attempt to try the format out. There have been none since. Yes, the Doctor travels into Earth’s past, but it’s always just another exotic backdrop to the SF.

Lionheart: William Hartnell and Julian Glover as the first Doctor and Richard I

Source: BBC

But if the pure historical format failed, that doesn’t mean there weren’t some gems among them. Undoubtedly the best is The Crusade, set in the Holy Land between the rival armies of Richard the Lionheart and Saladdin. The strength of David Whitaker’s script lies in its maturity. It treats both sides equally - this is no comic strip conflict between heroic Anglos and shifty Arabs.

It also puts the female characters on more even footing with the male ones. Jean Marsh’s Joanna, Richard I’s sister, chafes at the role life as royal has thrust upon her, and Tardis traveller Barbara gets the rough end of the stick at the hands of the nasty Emir El Akir.

Unfortunately, the BBC wiped The Crusade master tape many years ago, and only two episodes have been discovered and returned to the archive. But the soundtrack exists in its entirety. If you’re after something to watch as well as listen to, The Aztecs is another of the better historicals. It nicely combines a splendidly villainous John Ringham channelling Lawrence Olivier as chief priest Tlotoxl with a serious consideration of the impact of travelling in time and messing about with history.

The Daleks

By modern standards The Daleks - née The Mutants - is overlong and slow, but it remains the defining story of the show’s first season, and in many ways set the pattern for the show as a whole, thanks to the input of Story Editor David Whitaker. You have to wonder, how much of The Daleks is really Whitaker rather than credited writer Terry Nation, especially given how his famous creations so quickly became the yelling pantomime baddies we’ve come to know and love.

Not so here. In their debut story, the Daleks are calculating, scheming intelligences, their voices staccato but their dialogue purposeful and considered. There is a very real sense of their origins as people who, simply in order to survive, had to let go of much of their organic selves, and ultimately their sanity, to shelter in their metal shells.

Dalek revelation: the first time we see them in full

Source: BBC

Hidden below the surface of Skaro all these centuries, they’ve become isolated from the world above. Unsure whether it’s safe to pop open the hatches of their glorified nuclear bunker, they don’t know that life has managed to cling on up there, and it’s a shock when they find out it has. An existential shock too. If the Thals were able to retain their humanity despite the blasted environment, why the heck didn’t we? That’s a question too shocking in its implications to face - easier, then, to exterminate the beings that pose it.

The Doctor and his companions stop them, of course. War is bad, but giving in to oppression is worse - that’s the moral here, and it’s not surprising coming less than 20 years after the end of World War II. The Daleks is seen as a nod to the fight against fascism, and the creatures’ dislike of the unlike becomes manifest through their encounter with the lead characters and, later, the Thals.

And Doctor Who itself gets its first story in which the Doctor has to fight the baddies because it’s more important to stop evil than to maintain the integrity of one’s own anti-violence or non-interventionist philosophy. From this point on, for all the Doctor likes to trumpet his loathing of violence and force, he’s nonetheless always able to use it for the greater good.

Genesis of the Daleks

The trouble was, the Daleks just got silly. Originally, intelligent well-realised beings, by their second Doctor Who appearance they had become shouty comic fascists beloved by kids and Terry Nation’s bank manager. In the late 1960s, Nation attempted to free them from the Doctor and launch them in the US. He failed but it kept the Daleks away from Doctor Who until they were shoehorned into a almost cameo role in 1972’s season opener, Day of the Daleks.

By the time of Tom Baker’s first season, Producer Philip Hinchcliffe and Script Editor Robert Holmes knew that the punters still loved the Daleks, and that nothing would stake Baker’s claim on the title role like an encounter with them. But neither wanted yet another daft runaround like the baddies’ previous outing, Death to the Daleks. So they went right back to basics and commissioned Nation to write the story of the Daleks’ creation.

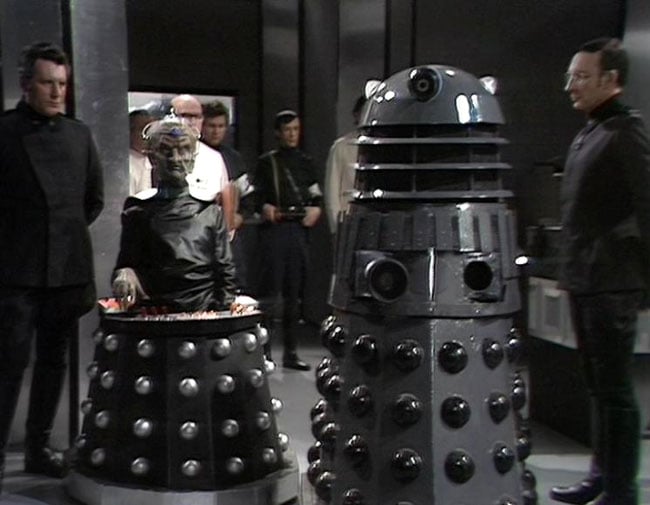

Davros and the Mk.III Travel Machine

Source: BBC

The result was the debut of Davros, the wheelchair bound boffin not only willing to contemplate what the outcome of a thousand-year war might do to his fellow Kaleds but to devise a means by which they might survive. Of course, when the Doctor arrives, sent by the Time Lords to hinder the Daleks’ development, he triggers a series of events which puts Davros directly in conflict with his own people and arguably precipitates the worst of the Daleks’ tendencies.

Played with admirable and spot-on restraint Michael Wisher - this Davros is not the cartoon of his later incarnations - the Kaled chief scientist is an intelligent rational being who has weighed morality against survival and found the balance favouring the latter. Especially when it then becomes a matter of personal survival. He’s ruthless, sure, but even he hasn’t entirely lost his humanity, as his final act, at attempt to blow up his bunker and destroy the first Daleks, reveals. He realises right at the end he has raised his offspring too well. They don’t need dad any more.

And, of course, the Doctor, for once, can’t win either. In one great scene, the Doctor questions whether he should kill all the Daleks, no matter how many future lives it will spare. Sarah’s all for it of course. The decision is literally taken out of his hands, but we all know the Daleks have to survive if the Doctor’s first incarnation to meet them hundreds of years later.

Inferno

Famously described by its director, the late Douglas Camfield, as “Doctor Who’s first nightmare”, Inferno is indeed a dark tale, written by Don Houghton but given its real power by Camfield’s vision.

Inferno starts off like almost every other Jon Pertwee story of the period: UNIT is overseeing a secret government project led by a arrogant, egocentric boffin. This time, it’s all about drilling through the Earth’s crust to expose a powerful new energy source, but it’s not long before it’s pumping out an acute mutagenic substance - green slime, natch - that sends those infected on murderous rampages.

Mirror world: the Doctor encounters alternative Unit personnel

Source: BBC

The Doctor tries to find out what’s going on, but he’s really keener to use the facility’s reactor for his own ends: getting the Tardis working. Fling him away from our Earth is does, but into a parallel universe where Britain has become a twisted totalitarian reflection of the real world. Here, the project’s leader, Professor Stahlman, has got closer to his goal, and the Doctor gets to see the outcome, though not before he’s beaten up under interrogation by the fascist forces.

Penetrating the Earth’s crust triggers a global volcanic catastrophe, and the Earth dies “screaming out its rage”. Decency and self-sacrifice hasn’t entirely died out, however, and the Doctor is able to escape the planetwide conflagration to prevent its repetition in his own universe.

How do you convincingly portray the end of the world on a 1970s Doctor Who budget? You can’t rely on special effects, so Camfield used loud sounds, a red lens filter and canny shots of smouldering extras huddled in ruins awaiting death by lava like so many of Pompeii’s victims. And just kept the tensions building up and up past the point where you don’t need to see what’s happening, you’re imagination is doing all the work.

It’s rare for Doctor Who to deal with disaster so intelligently, sensitively and imaginatively. Just ignore the bad monster make up, OK?

The Robot of Death

During the Trial of a Time Lord season, the Doctor Who production team tried to do a take on Murder on the Orient Express. It was called Terror of the Vervoids and it was, to put in a word of four letters, crap. They should have looked back at Chris Boucher’s 1977 story The Robots of Death. It’s the same notion - isolated crew get bumped off one by one, Doctor immediately suspected but sorts it out in the end - but carried off with far more aplomb.

Partly that’s the result of Boucher’s well plotted and nicely penned script, but it owes as much to the “creepy mechanical men” - the titular robots. Their design sells the story: these are not clunky, prosaic mechanisms but aesthetically beautiful creations that, but for their lack of facial movement and their near-silent motion, almost appear to be organic beings. They’re not, of course, and that allows the Doctor to talk about body language and non-verbal human communication years before computer graphics people began talking about the “uncanny valley” - the point at a representation of a human becomes so real it’s unreal.

D84 and Leela: great companions, both

Source: BBC

The title is no giveaway: we get to see how lethal the robots are almost at the start of the story. It’s hard to beat the corrupted robots’ glowing red eyes - fizzing like snow on an old, untuned telly - for creepiness, especially when their first victim’s dying scream echoes around the corridors of the sandminer. The Doctor, of course, lands right in the thick of things: the miner is about to scoop minerals out of a 1000mph sandstorm.

There are flaws: the robots’ silver-sprayed Marigold washing-up gloves. Taren Capel, human-raised-by-robots who’s behind the deaths is your stereotypical shouting loon, and initially appears masked solely to baffle the viewer not the robot he’s about to subvert. The Doctor gets unappealing snide at times. There’s some iffy acting - Tania Rogers as Zilda - but Russell Hunter as Uvanov, Pamela Salem as Toos and David Collings as Poul more than compensate.

Special word has to go to Gregory de Polnay as robot secret agent D84. He’s masquerading as a D-class ‘droid - “‘D’ for dumb; can’t talk,” Uvanov tells Leela. But D84 speaks to the Doctor with intelligence and pathos. He’s is one of the great companions who never were, and would have worth a thousand K9s.

Pyramids of Mars

Can there be a British man in his 40s who doesn’t recall shuddering with fear at this tale’s massive Egyptian mummies stalking woods, breaking free of mantraps and crushing fear-filled poachers?

Pyramids of Mars went out under the name Stephen Harris, but it was actually written by Lewis Grieffer and then heavily rewritten - hence the pseudonym - by Script Editor Robert Holmes. It is, of course, a take on the old ‘trapped in a building full of baddies’ plot - Aliens, Die Hard, etc, etc, etc - but here skilfully combined with an ancient god buried beneath under the sands of Egypt and eager to be free.

This being Doctor Who, of course the god is an alien, his mummies robots, and his hold on Marcus Scarman, the Egyptologist who uncovers his ‘tomb’, mental not magic.

I want my mummy! How Doctor Who deals with poachers

Source: BBC

Scarman is sent back to Edwardian England to hasten his master’s release from bondage, and a claustrophobic setting. His gaff’s grounds are isolated within a force field, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere of impending doom. Holmes helps it along with a small cast of well-drawn characters who have lives that extend into the story, though none survive beyond it. You care as they get bumped off: wrinkly old Collins the butler; Dr Warlock, Scarman’s worried chum; Laurence Scarman, the Egyptologist’s younger brother and a budding radio-astronomer - all bumped off on the orders of the silky voiced Sutekh the Destroyer.

Hats off to actor Gabriel Woolf: never was a Doctor Who villain more chillingly voiced than Sutekh. He never rages, never yells; his anger is always tightly controlled, cracking through the surface only when he realises he isn’t going to break free after all. Woolf even gives Sutekh a small, cautious frisson of joy when it looks like he might be about to escape his centuries of imprisonment.

It’s Holmes’ characterisation, brought alive by some fine acting, that really makes this story. Apart from a few duff shots - the Doctor sees the robot mummies before the script says he supposed to have, for instance - and an effects man’s hand famously slipping into shot, it’s a well directed piece too.

Tom Baker’s era doesn’t get much better, and many would argue neither does the rest of the show’s history.

The War Games

Ten episodes long, there are moments when, watching The War Games, you feel you’ve been pressed and sent to boot camp yourself. Fortunately, there aren’t may such moments as, by and large, this story cracks on at a decent pace - which isn’t bad for a story that started out much shorter and had to be extended when another script fell through.

That The War Games works is down to a strong script from Terrance Dicks and Malcolm Hulke, writers who could always be relied on to come up with a solid adventure story. This is first and foremost an entertaining romp. David Maloney was one of Doctor Who’s most consistently good and imaginative directors - he did Genesis of the Daleks - and it shows here in its evocation of World War I trench warfare and the mysterious aliens who appear to be running the show.

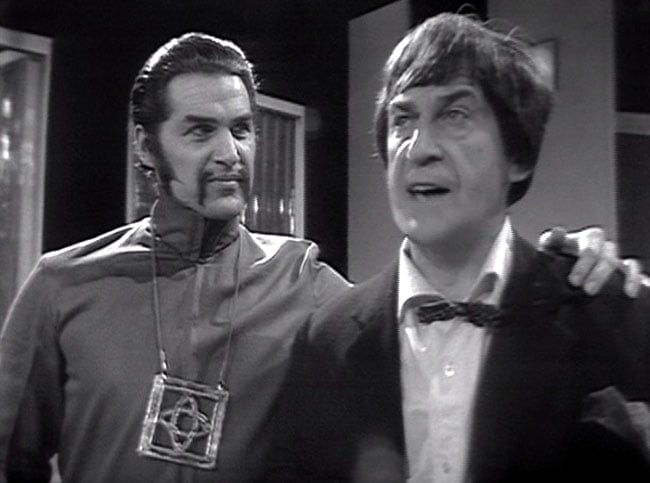

Masterly: the War Chief and the Doctor

Source: BBC

The story builds up the mystery - are we where we think we are? - through the first few episodes, then lets the Doctor get on with figuring out how to deal with it. We’re given plenty of clues as to the origins of the aliens’ ally, the War Chief, and his Sidrat device, but not once do Dicks or Hulke insult our intelligence by spelling it out.

Of course, there’s padding, especially around the middle, but the story builds to its conclusion - and with it the introduction of a race we’re now familiar with but had never heard or conceived of up to that point: the Time Lords. Along the way we get some surreal technology so advanced it looks like magic - eye glasses and monocles as hypnosis devices, anyone? - and some very funky 1960s interior decor.

The War Games was the final story of Patrick Troughton’s era and its a perfect showcase for the talent that made him such a good Doctor and consequently the prototype for so many of the actors that followed him. It takes an actor of Troughton’s calibre to build a convincing character on just two facial expressions: a scowl and an open-faced smile. The Doctor’s attempt to hoodwink the governor of a military prison with nothing but bolshie bravado is a joy to watch.

Bubbling Under

With 155-odd stories from Doctor Who’s first 30 years to choose from, it was tough selecting the best ten. Yes, there’s a lot of tosh, but inevitably some favourites had to be dropped. Here’s list of the ones that almost made the cut: The Tenth Planet, The Faceless Ones, The Ice Warriors, The Web of Fear, Terror of the Autons, Day of the Daleks, The Sea Devils, The Three Doctors, Carnival of Monsters, The Green Death, The Time Warrior, The Sontaran Experiment, Terror of the Zygons, Planet of Evil, The Brain of Morbius, The Hand of Fear, The Deadly Assassin, The Face of Evil, The Talons Of Weng-Chiang, Horror of Fang Rock, Image of the Fendahl, Warriors' Gate, The Keeper of Traken, The Visitation, Kinda, Earthshock, The Five Doctors, Ghost Light.