Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/10/09/science_museum_3d_printing_exhibition/

Printing the Future: See a few of UK’s 6.2 million 3D-printed ‘things’

The Science Museum examines additive manufacturing

Posted in Personal Tech, 9th October 2013 08:04 GMT

Monitor is an occasional column written at the crossroads where the arts, popular culture and technology intersect.

Listen to many of today’s bright, young and entrepreneurial things and you could be forgiven for coming away with the notion that every product we buy in the not-too-distant future will have been manufactured by a 3D printer from blueprints downloaded from the internet. The future, they say, will no longer be televised – it will be printed.

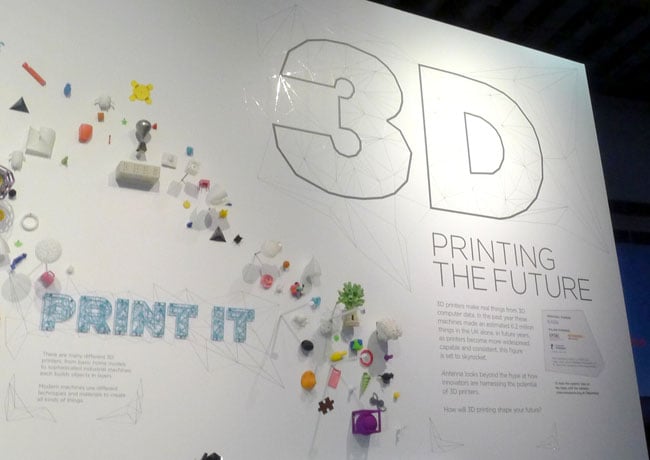

3D: Printing the Future, the title of a new exhibition opening this week at London’s Science Museum, lacks the questionmark a more sceptical or more cautious curator might have added, but the presentation itself seems open to the idea that 3D printing may not be the immediate future of manufacturing after all.

Many of 3D printing’s more interesting uses are medical, not domestic

It’s certainly easy to be wowed by the thought of punching out our own thingummies and doohickeys at home. As Jenifer Howard, marketing chief at Makerbot, a producer of desktop 3D printers, is quoted by the exhibition as saying, “3D printing has been around for over 25 years. It’s only recently that consumer 3D printing has become popular”. It has “inspired a creative explosion”, says exhibition organiser Suzy Antoniw.

Additive manufacturing does indeed appear to be nearing the mainstream. Only last week, Dixons stores PC World and Curry’s announced they are now selling a £1,100 3D printer, the Cube, on their websites. Ordinary folk wondering what all the fuss is about, and what 3D printing might be able to accomplish, will have it all cogently explained by 3D: Printing the Future.

The exhibition’s centrepiece is a huge canvas to which more than 600 3D printed objects have been attached. Some objects model the biological, featuring: skulls, human, alligator and tyrannosaur, the latter modelled in miniature wireframe; the rippled surface of the brain; a selection of false teeth; prosthetic limbs and kneecaps.

Others are architectural and mechanical: Notre Dame cathedral and Venice’s Campanile di San Marco; engine parts formed by combining 3D printing plastics with particles of steel; Bloodhound supersonic car steering wheels; many mathematical and geometrical shapes.

Crank them out: a model aero engine made with printed parts

There are rather a lot, however, of the chess pieces, human figures, sea shells, Iron Man masks and such you always see snaps of in articles about 3D printing, or in the windows of the world’s few commercial print shops. There’s one, iMakr, just around the corner from Vulture Central. Not a great deal of imagination being shown here.

The exhibition’s selection of objects - ‘things’ as it calls them - is loosely tied to the three areas in which 3D printing technology is finding a home and around which the presentation is organised: industrial, medical and consumer, each of which has a separate selection of more relevant items.

The medical section has perhaps the largest showing. No surprise, this, since the exhibition is housed in the Science Museum’s Wellcome Wing, funded by the Wellcome Trust, a medical charity. It presents prints from patients’ skulls, which are scanned and then digitally modelled before being output to aid surgeons’ efforts at reconstructive surgery. Other, less familiar objects are revealed to be foundations on which bone and flesh can be grown before being implanted to replace damaged or diseased tissue.

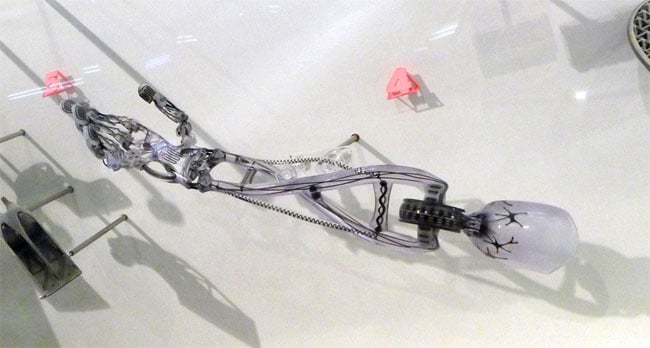

For medics, 3D printing provides a way to create inexpensive implants tailored to each patient instead of fitting them with low-cost generic spares or expensive tailor-made ones, says curator Suzy Antoniw. Among the exhibits is a concept prosthetic forearm and hand, developed by a team at Nottingham University, itself something of a 3D printing powerhouse and a contributor of many of the exhibition’s objects.

Would you ride a printed bike?

The arm truly signals the emerging nature of 3D printing: many of the applications discussed here are conceptual. The technology exists, but no one quite knows what to do with it, or whether it’s able to deliver the solutions they think it might be able to. How about printing flexible cellular material?

“We have to know printed organs will work and keep working. We can’t just pop something inside someone and hope it will work,” says Professor Brian Derby of the University of Manchester and a specialist in biomedical printing on one of the exhibition’s information panels. “Even if we can print a whole organ, there will be at least a decade of testing before this comes close to reality.”

Derby’s words aren’t the only ones to express reservations that 3D printing might not be about to trigger a medical or industrial revolution. All of the exhibition’s interactive information panels contain quotes from some of the industry’s more cautious participants.

In fact, 3D: Printing the Future unintentionally reveals there are two 3D printing worlds: the one in which engineers and doctors are carefully working toward real, practical and useful goals, and one inhabited by ebullient enthusiasts with a less considered view of the potential of 3D printing.

Yes, but is it art?

It’s clear from the exhibition that medical and industrial applications are emerging but slowly, as practitioners experiment with the technique to see what it may be able to achieve. It’s certainly happening – more than 5.5 million people around the world have been treated using 3D printed parts, we’re told – but it’s a revolution waiting to happen.

“A printer needs to heat up and takes hours to print one thing. The cost of a million people printing in a million different places will be huge,” warns Phil Reeves of Econolyst, a 3D printing consultancy, on one panel. “You’re better off producing things in factories, where it takes 15 seconds.”

Best thing since sliced bread, or a technological appendix?

Cautious comments like these are in marked contrast to others, expressed in the consumer section, which seem to suggest we’re on the verge of utopia thanks to 3D printing in the home.

There was much the same kind of buzz around laser (2D) printers back in the mid-1980s, as it became clear to a number of pundits and punters that here was the technology that would ‘democratise’ the publishing business by allowing ordinary folk to create newspapers, magazines and books at home, right from their own personal computer.

This is the same notion that drives many a proponent of 3D printing: that it will take the power of production away from the corporations and put it in the hands of the people.

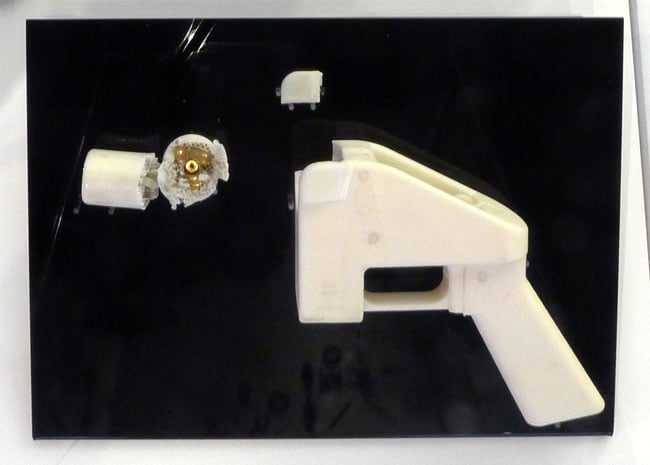

Liberator shows the limits of 3D printing

They haven’t learned from history. The early laser printers were unable to match the quality of a printing press. It took them decades to evolve that far, during which time expensive but high quality output became the province not of the people but of a new breed of output bureau. With it the economics of print changed, and we’re now at the stage where you don’t need to print your publication on a laser printer and hand-staple it - you get it printed online.

Assuming, of course, that you print it at all. It wasn’t low-cost printing that gave World+Dog the ability to publish at will: it was the web, a technology few could conceive in the mid-1980s and even then not as the truly democratic medium it has become today.

There seems little understanding in consumer 3D printing world is aware that some other approach or business model could yet emerge to supplant it. Creating good 3D computer models is as hard to do today as designing good magazine layouts was in the 1980s. Sure, the software tools were there, but what was lacking in many of their users was the skill to use them effectively. That’s just as true of 3D printing now.

Are we about to see a mass of 3D printed objects that are the poorly designed equivalents of all those desktop published pamphlets full of enormous drop-capitals, unsubtle drop-shadows and clip-art? So many 3D printed objects are already becoming clichés of the form.

Is 3D printing’s reach not up to its grasp?

3D: Printing the Future ignores these, more negative scenarios. Here’s another. As we’ve seen with the rise of online ticket sales, we’re now expected to not only pay for tickets but to print them ourselves too. How soon before products cease to be available as physical goods – no one’s visiting the High Street nowadays, in any case – and you have to buy a new pair of trainers as a download to churn out on your home printer?

No need to worry: “A factory can churn out lots of identical items much more efficiently [than 3D printing can],” says Econolyst’s Phil Reeves. “3D printing’s edge is making detailed one-off items that can’t be made efficiently other ways.”

Indeed, the exhibition does include some 3D printed items that really shouldn’t have been. There’s a 3D printed balloon dog - surely making it out of, well, balloons would have been easier, cheaper and taken less time?

There’s also a very fine near full-size model of a radial aero engine, cut away in places to show the pistons and driven by a hand crank. Impressive, but of course while it’s made from 3D printed parts, they still needed to be manually combined into the final working replica. Elsewhere, a pair of mechanical hands rely on strings and wires, added later, to operate. Again, the limits of 3D printing are tacitly shown.

What about the handful of 3D-printed music box mechanisms on show? Alas, they’re kept within a glass cabinet so we can’t see what tune they play. Their delicacy and do-not-touch display suggests they wouldn’t take kindly to rough handling, something of a problem for many a product suggested as a candidate for 3D printing.

Is it though?

And then there’s the Liberator, widely hailed a year or so ago the first gun to be constructed from 3D printed parts. The exhibition presents it complete - or should that be ‘incomplete’? - with its mangled, bullet-torn barrel. Here is an application for which 3D printing is not yet, if it ever will be, applicable.

Perhaps 3D: Printing the Future’s most telling point are two statistics it presents, separately. First, in the past 12 months 3D printers have churned out “an estimated 6.2 million things in the UK alone”. Second, “in the UK alone around 4.8 million 3D printed things are made by enthusiasts each year.”

In other words, fewer than 20 per cent of the output from British 3D printers was generated by manufacturers and others with a real application in mind.

3D printing may well be the future of manufacturing, but for now it’s a hobbyist’s toy.®