Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/09/06/nokia_rise_and_fall/

Finns, roamers, Nokia: So long, and thanks for all the phones

The rise and fall of the great Finnish phonemaker

Posted in On-Prem, 6th September 2013 09:03 GMT

Special Report Finns are in mourning this week after Nokia has sold its mobile phones unit to Microsoft: a decision that weirdly seems both inevitable and shocking at the same time.

But they should be proud, for Nokia had an incredible 15-year run at the top of an entirely new industry, making stalwarts like Motorola and neighbours Ericsson look clumsy and slow. It outlasted both, and gave the world Nordic design and simplicity and top-notch engineering: all influenced by Finland’s world-class education system.

The company also reflected Finland’s outward-looking nature, even if not everyone knew where Finland was. I recall signing a lease with a Californian in 1999 who told me how much he loved Japanese technology products: “Sony – but most of all Nokia,” he said.

The affection the Nokia brand retains owes much to creating simple usable technology products in the 1990s and well into the noughties.

The rise

Surely everyone now knows by now that Nokia began life as a cable and rubber boot manufacturer in the 19th century. Nokia Ab, Finnish Cable Works and Finnish Rubber Works made it official in 1967, merging into the Nokia Corporation. By the late '70s Nokia created the radio telephone company Mobira Oy as a joint venture with Finnish TV-making firm Salora in 1979.

But Nokia only really became a recognisable name in 1982 when Nokia introduced a hefty (nearly 10kg) car phone called the Mobira Senator one year after the first international cellular network, the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) service was up and running in Finland.

Back then, Nokia resembled an obscure Korean chaebol. The company was owned by the banks, and many of its buyers were the state or state agencies. It decided to adopt a new, optimistic and quite fearless business strategy.

Nokia examined its products where it led the market and where it followed a market leader with a "me-too" offering, and decided it had too many of the latter and not enough of the former.

Yet it could change that, by capitalising on Finland’s human capital, its engineering and language resources. Nokia had only 907 staff (out of 23,000) working in R&D in 1983 when the sea change began. Nokia briefly became the market leader for analogue carphones in the late 1980s but the success threatened to be buried by the company’s other poorly performing units.

In the late '80s, the Finnish economy started to liberalise and sweeping changes were seen across the country's business landscape.

Between 1989 and 1993 the company was a mess: it sold TVs and PCs among many other products, as the results of acquisitions. When in January 1992 the new CEO Jorma Ollila took over, mobile phone revenue accounted for just 1.1bn Finnish Marka, out of £6bn FIM total sales – with “cables and machinery” accounting for 1.67bn FIM.

Olilla’s plan was to become the leader in mobile phones, and the Nokia board considered it so risky they put their caution on the record, and demanded Ollila produce a "Plan B": in his strategy, Nokia would have to get much smaller before it got bigger.

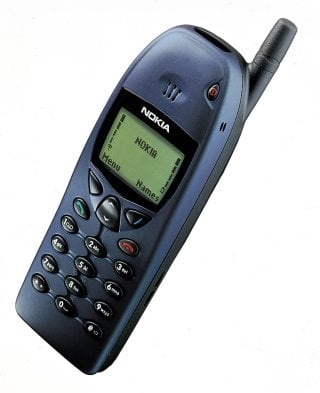

The Nokia 6110 from 1997. The first with icons and Snake.

Aimed at what Nokia called the 'Controllers' segment: business users

In fact, Ollila’s decision to "bet the company" on mobiles was spectacularly prescient. The airwaves were becoming deregulated, and it was no longer viable for one (or two) operators – one of which was state-owned – to enjoy the privilege.

More operators meant more customers for Nokia, and it also meant ordinary consumers could join the market. Which in turn meant manufacturers would have to market mobile phones in an entirely new way. Rather than taking the CIO out for lunch, they had to be easy to use, feel personal and even fun.

Ollila anticipated all of this. As the boss of the mobile division, he was confident that a single digital standard would also lower costs and drive adoption. In 1983, McKinsey had predicted that the global market for mobile phones would by the year 2000 be around 1 million subscribers.

The company soon become intricately involved with the development of cellphone networks.

It’s Nokia’s confidence, ambition and international outlook that really stand out in these years. By 1994 Nokia was publishing its board minutes in English. Meanwhile Motorola's annual company report that year finds a $22bn giant keen to talk about its two-way data pagers and the Iridium satellite network: "The first operational global wireless telecommunication network enabling subscribers to make or receive telephone calls over handheld subscriber equipment worldwide".(PDF)

By 1998 Nokia was shipping more mobile phones than anyone else.

As well as targeting simplicity, Nokia was doing things rivals didn’t dare contemplate: such as removable fascia for personalising the device. Nokia’s neighbour and swankier rival, LM Ericsson, also employed superb designers – but by the end of the 1990s had made a marketing virtue out of the distinctive stubby antennas on its mobiles. Nokia simply made the external antenna disappear, into the phone. Ericsson was the first of the three GSM giants to sell off its mobile phones division, in 2001.

The Fall

During the first part of the new millennium arrogance and complacency began to become noticeable. Ollila was a formidable intellect, and the successful management team of the early 1990s had penned such doctoral dissertations with titles such as as "Ownership Strategy and Competitive Advantage" (Timo Koski) and "The Internationalization of Industrial Systems Suppliers" (from corporate planner, Mikko Kosinen). Ollila was also drawn to theory, not always wisely.

Nokia’s rapid decline is well documented, not least here, and can be encapsulated in a single sentence: it failed to respond as the market demand changed. But it’s more complicated and agonising than that. Many companies fail to anticipate such a change, while others over-estimate the appeal of their existing products As a result, when the wind changes, they have no Plan B. The wealthy ones can buy their way out of trouble, but most cannot.

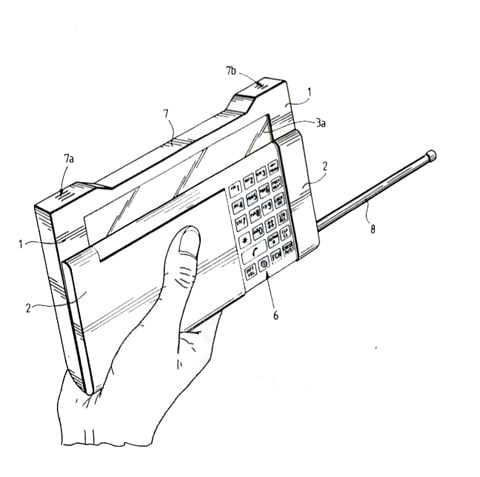

Nokia filed this patent for a Communicator device in 1991

What's singular about Nokia's fall was that it had not only anticipated this change in the market, but spent years preparing for it. It had a Plan B - it was just too slow bringing it to market.

Former Nokians cite the Ollila’s 2004 "matrix reorganisation" as critical in the company’s fate. This had two consequences: one was that internal teams were competing against each other in ways which the consensus management could not adequately resolve. Another was that it emphasised Nokia’s weaknesses rather than its strengths.

The reorg established software development as a kind of factory production line from which product managers could pick and choose what they needed. It looked great on paper, but Nokia was never very good at writing software once the requirements for that software became remote from the needs of the punter.

You can, perhaps, argue that this happens whenever the spec is poor, or vague. But it made product managers far more remote from their own supply chain. The entrepreneurial flair of the 1990s gave way to factional in-fighting and dozens of lost opportunities. For more on this matrix reorg, see El Reg's "When Dilbert Came To Nokia", from 2010.

“Everyone at Nokia had read The Inventor’s Dilemma in 1998”, one former Nokian told me, referring to Clayton Christensen’s management book about how successful companies fail to adapt to change.

So, from 2002 Nokia began preparing for the day when mobile computers with some telephony integrated took over from telephones with some computer-like aspects... which began to happen when Apple announced the iPhone. Nokia had embarked on a mobile Linux which it finally revealed in May 2005, a touchscreen "Wi-Fi tablet" with three hours battery life, called the Nokia 770 Internet Tablet. Hardly anybody bought one, but Nokia kept plugging away. Subsequent iterations gained VoIP, and eventually full telephony. It was perfect for the post-iPhone world.

To ease the transition out of Symbian – the popular mobile OS used by many of the big names across the noughties – and attract more developers, Nokia needed a much easier cross-platform API, and it bought the best, Trolltech’s Qt.

Anssi Vanjoki, the popular executive who devised Nokia’s successful 1990s branding strategy and helped choose the segment of the Spanish guitar waltz Gran Vals to become the Nokia ringtone, declared that everything had been part of a deliberate process, and the next version, the fifth, would become Nokia’s mass-market platform.

"A true platform for the next generation of computers... We have what we believe is the platform that defines what computers have become," said Vanjoki. Nokia’s Plan B was perfect.

The problem was, he was saying this in 2009, not 2007.

.

.

"Nokia Media Terminal" - such a flair for names.

A Linux-based set top box from 2000

Apple didn't actually know how to make phones, and had to learn. Its very slow and gradual evolution of the iPhone – for two years it maintained carrier exclusives – gave Nokia every opportunity to regroup and respond. But the Linux platform still didn’t appear in a consumer smartphone for another two years. By which time, Vanjoki had gone, Nokia had ‘burned’ its platforms, torching almost all internal platform software development, and tying its fortune to Windows Phone.

It’s very tempting to speculate what might have been, if Nokia had revealed a competitive Qt-based Linux-based OS in 2008 and made the radical move of giving it away with no licensing fees – daring rivals to compete on design, on scale, and against Nokia’s formidable logistics and distribution operation. This would have been a bold leap as daring as Olilla’s gambit back in 1992, of betting the company on a mobile phone technology that didn’t really work at the time, of shrinking the company to give it focus and the chance to survive.

It’s possible that the technically crude and grossly inefficient Java-based system touted by a rather sinister American advertising company - Android - would never have gained much traction. Who knows? With an "Open Maemo" powering half the market, it might be Google who today is shopping around in desperation for a faded hardware OEM.

Perhaps. Or perhaps it wouldn’t have mattered. Nokia tried and failed to interest potential partners in the Linux platform – but by then Android was irrepressible. The entire industry from telcos to retailers were demanding something competitive to go up against the iPhone, which lacked decent competition. Android filled the vacuum.

But we do know today why Nokia was so slow – via Taskamuro, which we translated and summarised here. It was in-fighting and bureaucracy, and an indecisive consensus management that lacked leadership and urgency. Nokia had “wasted 2,000 man years on UIs that didn’t work” – and do read this for a sense of the chaos at the organisation. Ollila had hoped the Darwinian competition introduced in the 2004 reorg would prevent the creation of a bureaucracy. It didn’t.

Wierdly, Nokia also anticipated social media. In late 2002 it helped host a private "social software summit" with Clay Shirky – an event full of the anti-human robot sociology now synonymous with Shirky, but Nokia was at least shrewdly anticipating future uses of mobile devices. It failed to start a social network, buy into one, or even support them well with its Symbian phones. Another lost opportunity.

The couple of years that followed after Ollila was succeeded by CFO Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo ("OPK") were really the years of madness. Nokia had completely lost the plot. At times Nokia resembled a very earnest NGO. It started a banking service for people in India who didn't have bank accounts. Attendees to its annual partner event, Nokia World, had to get used to hearing New Age whale song.

Thanks for all the phones

One interesting thing emerges from reading the business hagiographies written in Nokia’s heyday. It’s how wide of the mark it is with its assumptions. For example, this gem contains life-sapping crossheads (I’ve picked these three at random) like "Transitions in the Leadership Journey", "Dream Teams are Diverse Teams" and "Why Nokia’s Matrix Works" – and was published in 2010, no less. But very little is relevant today. Take for example, standards.

The success of GSM and 3G suggested that partnerships and standards were vital, and with Europe as a whole having a more consensual culture than the US, its varied countrymen were better at these – therefore Europe would continue to lead the mobile industry, through a consensus of equipment producers. These would choose what services we have, and the way we use them. But Apple and Google really disproved much of that. This was an illusion that lasted a few years.

As Charles Davies pointed out here: "The time Apple made its first iPhone was about the first time that anyone who wasn't already incumbent could."

Packaged silicon with a smartphone on a chip allowed newcomers to enter the market and try something new. So, for the first time, Nokia was up against consumer electronics giants.

As Tero Kuittinen writes: "the global demand surge for mobile handsets was something leading consumer electronics firms like Apple, Siemens, Sony and Philips could not foresee. So Nokia ended up competing with two lumbering, erratic messes called Ericsson and Motorola. Compared to those two main rivals, Nokia looked like a blazing ball of consumer-friendliness."

Samsung and Apple provide very different competition.

In early 2004 I rashly predicted that Nokia and Apple could seriously challenge Sony's end-to-end mastery of the computer electronics business, and could begin to set standards and create new markets. Apple was a small boutique PC manufacturer but had an unexpected hit with a pricey music player the iPod. Nokia had great design, scale and distribution. Looks like I was right about one of those challenges, but not the other. Why?

Nokia in the 1990s tried to delight the individual, but in the decade that followed it decided that its customer was the networks. Apple looked at the reality of smartphones, which was a miserable experience accessing data or apps, and saw unfulfilled potential. It focused on the individual, to the extent of putting in a graphics processor capable of drawing 60 frames per second.

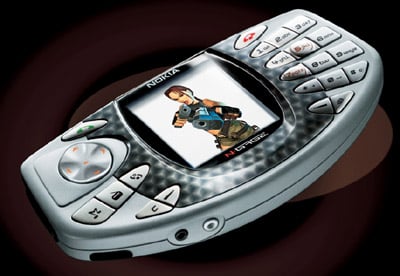

The idea of a Nokia console promised high volumes for games developers, with the reality of the NGage fell short

Nokia couldn't translate the barnstorming inventiveness of the 1990s to new markets. Always decent and ethical, perhaps it was simply not ruthless enough.

It remains to be seen whether Nokia under Microsoft management has the motivation to produce outstanding products. Its track record this year has been excellent, and surprising. It has made leaps in market share thanks to low-cost devices, and at the high end it has produced a quite insane, mind-boggling bit of engineering in the 1020 imaging unit.

This expertise has been acquired intact by Microsoft, for a small price. Will the ex-Nokia mobile team gain from its closeness to the Windows Phone team, and make products such as the Lumia 1020 even better – something Ballmer said he wanted? Or will the Microsoft bureaucracy grind it down, as it did with Danger Inc – the last handset manufacturer Microsoft acquired. We’ll have to wait and see. But Nokia's rapid fall shouldn't let us forget what an unusual and well-deserved success it was on the way up. ®