Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/08/30/50_years_of_the_compact_cassette/

Are you for reel? How the Compact Cassette struck a chord for millions

From fuss-free audio tape recording to Walkmans, it's all in your head

Posted in Personal Tech, 30th August 2013 15:04 GMT

Feature On 30 August, 1963, a new bit of sound recording tech that was to change the lifestyle of millions was revealed at the Berlin Radio Show.

The adoption of the standard that followed led to a huge swath of related technological applications that had not been envisaged by its maker; for Philips, the unveiling of its new Compact Cassette tape and accompanying recorder was about enticing people to buy a fuss-free portable recording system.

The Philips EL 3300 cassette tape player and recorder

at the Berlin Radio Show in 1963

Source: Philips Company Archives

Sonically, the Compact Cassette recorder was no hi-fi and, from the start, was never meant to be. Instead, the company had succeeded in putting together a format for recording, storing and playing back audio that immediately made sense - and delivered so many convenient improvements over existing systems that its success was assured.

Although the Compact Cassette tape (now just known as the cassette tape) was a new design for handling tape media, what Philips had produced was an innovative approach to existing technologies rather than an out-and-out invention. Having decided on the format specifications of tape width, track width and tape speed, the firm's engineers went about designing the circuitry and physical mechanisms that would deliver acceptable results for dictation, among other tasks, and eventually music playback akin to a decent portable radio.

Indeed, the emphasis was very much on portability, and Philips had no intention of trying to match the fidelity of reel-to-reel recorders that had marker-pen-thick track widths and fast tape speeds. If you needed superlative sound quality, then those tape machines were there and would continue to be for many decades more in pro audio circles.

Hyper threading in the 1960s

Admittedly, with few exceptions, pro audio gear of the time wasn’t very portable as the tape reels were sizeable, and so was circuitry and motors required. Using smaller reels limited recording times and while slower speeds would extend this, their use did affect the overall sound quality. Also simply threading a tape into the gear could become quite problematic in challenging conditions such as, for instance, radio reporting on the move in a war zone. And to consider reel-to-reel tape as in-car entertainment was impractical at best.

Given a lack of alternatives, people took what was available and Philips made a portable reel-to-reel system for ordinary folk in the late 1950s, the EL 3585, which did exceptionally well. Buoyed by its success, Philips focused on portability, rather than high fidelity, as it considered how to package tape in a new format.

The popularity of its EL 3585 portable recorder led Philips to consider more compact options

Photo courtesy of Johan's Old Radios

The company didn’t have to look far either, as RCA Victor was already touting its own Sound Tape Cartridge which had a 0.25in-wide tape, but as it ran at 3.75 inches per second (IPS), it needed to be fairly large to hold enough tape to run for 30 minutes per side – on some models the head moved laterally, rather than requiring the tape to be flipped.

The Sound Tape Cartridge could hold stereo audio; alternatively, one could record in mono on all four tracks independently to get two hours out of it. Punters could drop down to 1.875 IPS to double the capacity, but the quality wasn’t particularly impressive. An archive RCA Victor advertisement from 1958 demonstrating the cartridge is embedded below. The fun starts at 7 minutes, 47 seconds.

In an interview with El Reg published here, Lou Ottens, the Compact Cassette team leader at Philips, noted that Peter Goldmark from US broadcaster CBS had proposed a single-reel cartridge with 0.15in width (3.81mm). Philips recognised that this narrower tape width was the way forward. It’s actually slightly larger than the eighth-of-an-inch that many people assume cassette tape to be.

Are you for reel?

Goldmark wasn’t alone in this cartridge proposal, though, as CBS had American manufacturing megacorp 3M on board. In 1959 and 1960, The Billboard magazine, as it was called then, was breaking stories about this emerging single-reel format, which, although short-lived, did deliver technological advances in tape particle formulation and used thinner tape. It was also three-track stereo, the third track apparently dedicated to recreating ambience and reverberation.

Indeed, the combined efforts of CBS and 3M proved that this narrower tape width running at 1.875 IPS was capable of sound reproduction that would be good enough for the consumer market. Punters would also welcome the lower per-minute recording costs that narrower and slower tape afforded. And having thinner tape allowed for smaller reels too, ideal for portability.

With this raw tape specification already established by 3M, Philips was able to get busy with designing a product. However, it disregarded the idea of a single-spool cartridge, which could be temperamental and needed to be rewound after use.

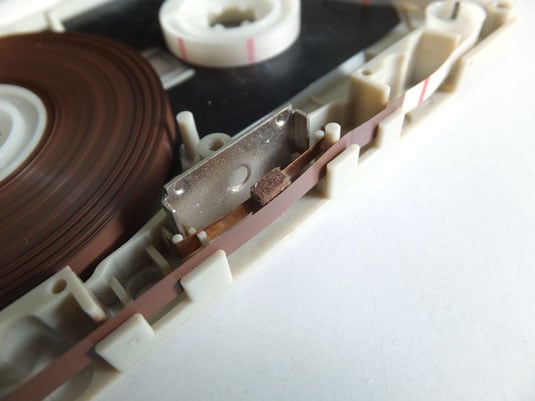

TDK Compact Cassette innards reveal reels without plastic flanges

Like some earlier encapsulated tape designs, the Compact Cassette did away with flanges, which are the protective outer rims on reel-to-reel spools that shield the actual tape (see the photo below). These large spools were always of a particular size and two were required, so you’d always need to make space for them both. Going flangeless meant that the tape hubs could be closer together and protected inside a case – it was yet another way of scaling everything down.

Tape reel – note the outer metal flange

On the subject the size, Philips had its own ideas on how big the Compact Cassette recorder should be and advances in electronics aided the process of fitting everything in. The emphasis was always on portability and, consequently, its engineers had to start from scratch.

The birth of a standard

Although established design principles for magnetic sound recording were observed, there’s quite a bit of give and take in the analogue world. This kept the dream of a handheld audio recorder alive, but Philips still had to make some important decisions regarding frequency response and acceptable levels of distortion. The battleground for these arguments lay in the bias and equalisation configurations.

As established decades earlier, simultaneously adding an inaudible high-frequency signal to audible sounds during recording dramatically improves the audio quality, thanks to the way magnetic tape heads work. This so-called AC bias dealt with coercivity issues inherent in magnetic media and, rather than go into the physics of it all, you can find plenty of material online explaining hysteresis loops and tape saturation.

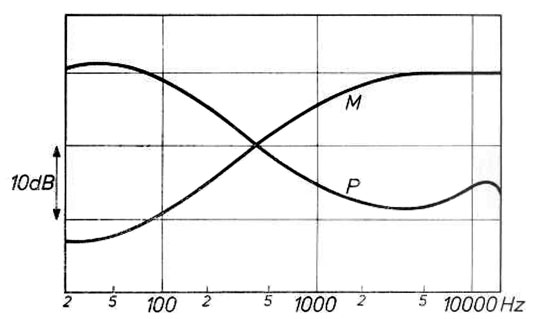

Compact Cassette EQ curve: M shows the variation of tape magnetisation across the frequency range

P shows corresponding playback characteristics. Source: Philips Technical Review

That said, choosing the level of bias current determines certain factors regarding frequency response, and Philips had to judge what was appropriate for its intended audience. A high bias field favoured lower frequencies whereas a small bias current suited higher frequencies. It’s all to do with where the signal gets recorded in the tape layer. Low frequencies are deeper into it whereas high frequencies are more on the surface.

Philips worked out a suitable compromise with a low bias current that favoured the high frequencies and utilised equalisation circuitry to boost treble when recording and conversely boost low frequencies on playback. Using EQ in this way was common in magnetic recording, yet the configurations Philips had devised needed to become standardised. The bias and EQ circuitry for every cassette recorder worldwide had to follow the company’s sound reproduction recipe. Apart from the cassette specifications, reference tapes of frequencies at precise levels would be used for calibration.

Micro management

Another factor in all this was the tape head, which is effectively an electromagnet whose poles are positioned just above the moving media. The tiny gap of the head (see the above diagram) determines the highest frequency that can be recorded. A gap of 2µm was chosen to achieve a theoretical maximum frequency of about 12kHz. For Philips, up to 10kHz was good enough and it worked out all its bias and record-playback EQ settings based around that gap dimension. A smaller head gap would lower the high frequency response but boost the recording strength, and so this was another critical part of the standard to be adhered to.

If everyone started customising the specs, tapes recorded on one machine would potentially sound dreadful when replayed on another. And in some respects, Dolby's noise reduction tech, which would eventually find its way into Compact Cassette recorders and dominated pre-recorded Compact Cassette production, has a lot to answer for.

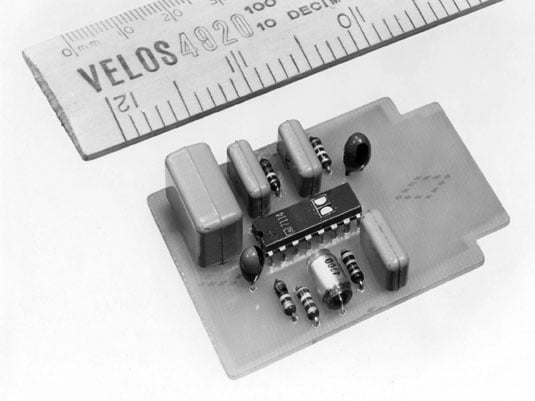

Dolby B noise reduction circuitry on a Signetics IC from 1973

As the tape needed to be flipped over, details of the recording track area were essential too, and as stereo recording had also been implicit during development, these track widths were crucial. The tape was capable of four tracks – a pair in each direction for two track heads – and these needed to be separated to avoid crosstalk.

In a mono arrangement, each track was 1.5mm per side across the 3.8mm tape width. For stereo, the left and right tracks were only 0.6mm apiece, with 0.3mm separation to avoid crosstalk. Needless to say, smaller track sizes did impact on the output of the left and right channels, but combined, the output was satisfactory, and Philips claimed cassettes reproduced better stereo separation than vinyl records.

Yet where a record turntable only had to rotate at a regular speed and the tone arm would do the rest, tape needed to be dragged from one spool onto another and across the erase, record-playback heads along the way and all at a constant speed.

Compact Cassette meets RCA Sound Tape Cartridge: note the exposed tape on the RCA media

Source: Wikimedia, Creative Commons

RCA’s approach included tiny tension arms used by reel-to-reel systems – you can see the slots for them on the sides of the cartridge. The need for these variable levers was to even out any slack in the tape transport and maintain good contact with the tape head array.

Single-spool cartridge formats, such as the Fidelipac, had no tension arms but made firm contact with the head by having pressure pads behind the tape. So when the cartridge was engaged, the tape was sandwiched between the head and a fibre pad.

Playing for reel

Despite being originally intended as a dictation machine, the free licensing of the Compact Cassette standard sparked widespread adoption by electronics manufacturers, particularly in Japan. In a relatively short time, technical advances in the recorder components and magnetic media led to a steady improvement in the performance of the format.

Consequently, the Musicassette - cassette tapes prerecorded with music - increased in popularity as the sound reproduction improved. Admittedly, some companies with interests in other formats held off mass production of Musicassettes of their artists’ catalogues, but they would be won over in the end.

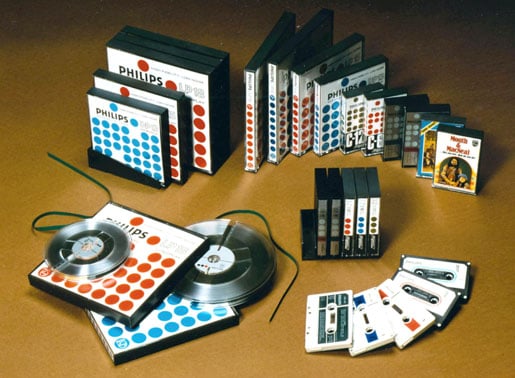

Philips Musicassettes and other tape media from 1965

Source: Philips Company Archives

The actual production of Musicassettes was done on machines running 32 times faster than normal playback. Cassette tape would be reeled over four heads recording what would be both sides at once at 60 IPS. The master tape that was source of the original music had been recorded at 7.5 IPS and this would also run 32 times faster, clocking up a playback speed of 240 IPS for duplication purposes.

A 1,500m reel of cassette tape was used for each run from which multiple Musicassettes would be made. Tones separating the programme material were used to identify the beginning and end of each completed Musicassettes album to aid splicing and packaging.

This super-fast tape transport also required the circuitry to follow suit. So instead of the bias frequency being around 80kHz, it was now 2.4MHz; the amplifiers also needed to work over a frequency range of 200kHz to 500kHz. The head gap was also enlarged to 4µm. This fast tape copying was the only way to knock out cassettes to production deadlines.

Highly sprung

Inside a Compact Cassette, there's a pressure pad that is an important component. It's mounted to a short piece of sprung metal that produces a contact force between 0.1N and 0.2N to keep the head comfortably against the tape.

Sprung pressure pad and the silver metal plate behind it, which provides shielding from stray magnetic fields

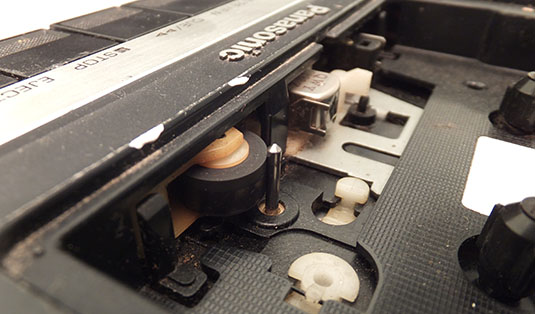

As on recorders before it, a capstan and pinch roller performed a similar sandwich act of pulling the tape through at a constant rate, like clothes through a mangle. That said, the 2mm diameter capstan Philips chose was precision made, and certainly not intended to mangle the tape, but if the capstan was bent or had an uneven surface, it could cause major problems not only to the tape but also wreck the feed speed.

The capstan – the thin, silvery, spindle in the cassette recorder – is the main component in governing the tape speed. It was much smaller than capstans on other recorders, which was needed to reduce its flywheel size, again, to keep the recorder portable. Using gearing, the same motor running the capstan would perform transport winds and determined tape take-up using a slipping clutch to decrease its speed as the empty spool filled up with tape.

Capstan and pinch roller on Panasonic RQ-2734 from 1976 and still working

All these aspects engaged when the tape was in play or record with the head array and pinch roller moving into place, rather than being fixed like on the RCA cartridge. For fast winds, the head assembly retracted, so there were no concerns of wear and tear caused by the head. The retracting array meant removal of the cassette posed no problems and also enabled the tape to be recessed slightly, and covered from both sides; protecting it when handled.

A bit of a flutter

With the motor driven by a current alternating at 32Hz, the capstan at 7.5Hz, the slipping clutch at 4.6Hz and the flywheel belt at 3Hz, this combination of components produced ‘flutter’ – minor, rapid speed variations in other words. It was something Philips couldn’t realistically eliminate on a consumer-focussed product. Instead, it had to set tolerances, weighting the acceptable limits against the audio world's DIN 45507 specification on frequency fluctuation.

Lest we forget that Philips wanted all of this to work its debut model, the EL 3300, from five 1.5V C cell batteries and to continue to function as the voltage supply declined from 7.5V to 5V or even less. The widespread use of transistors – a marvel of the age – made all this possible, with the EL 3300 also having to knock out 0.25W from its 2.4in loudspeaker or record from the supplied EL3797/00 moving-coil microphone and detachable EL3796/00 remote-control cable.

The first Compact Cassette recorder: Philips EL 3300. Source: Philips Company Archives

The front panel was sparse and the controls were a joystick of sorts, rather than the keys that would later dominate cassette machines. You’d need to hold down the separate red button before sliding the transport into the play position to engage recording. A quaint moving-coil meter to the right indicated the recording level and dials on the side controlled record and playback volumes. The two DIN sockets were for the mic and remote control functions.

The EL3300 measured up at 113 x 56 x 196 mm and weighed 1.5kg, which is certainly portable. It cost 300DM at launch, and it didn’t quite live up to the cassette spec potential: the audio frequency response topped out at about 6kHz; the later EL3302 would improve on this with claims of 10kHz.

In the US, the Philips recorders were marketed under the Norelco brand and in November 1964 were sold as the Carry Corder 150. As a result of Philips’ decision to license the format for free, the Compact Cassette’s popularity was assured. Being suitable for use in cars was another bonus, even though the 8-track ‘Stereo 8’ cartridge did make considerable in-roads here, as the cassette tape still needed refinements to become more listener-friendly for music.

Harman Kardon cassette deck with Dolby B from July 1970

Indeed, prerecorded Musicassettes didn’t appear until late 1965 in Europe and the following year in the US. The introduction of Dolby B noise reduction on hi-fi cassette recorders – the Advent Model 200 being the first in 1970 – started a proliferation of what was in effect an analogue codec on mass-produced Musicassettes.

While replaying without Dolby B would be acceptable, it did mean that the listener was hearing a bright and slightly compressed sound and not experiencing the original dynamic range or equalisation of the recording. An explanation of Dolby's ingenious analogue signal processing is featured here.

Making tracks

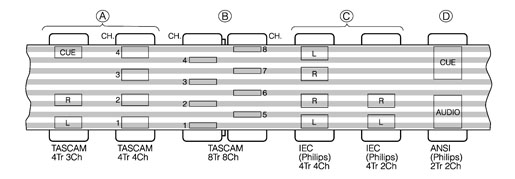

Fostex 250 4-track tape head

Despite being a Tascam trademark, the Portastudio - popular for taping demos and similar performances on a budget - stuck as shorthand for a multitrack cassette recorder. The early models allowed four-track recording, and the tape didn't have to be flipped over: you could use the whole of it in one go without having to pause, and at double speed, too.

Tascam and Philips tape track allocations

The speed allowed for better quality, but you’d only get 15 minutes out of a C-60 that would also need to be a CrO2 tape (made using chromium dioxide, which boosted the sound quality). Tracks could be independently recorded and played back, so you could build up a multi-instrumental and vocal recording.

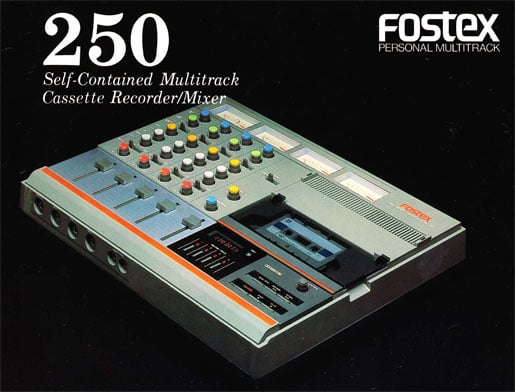

Fostex 250 multitrack cassette recorder

Also these portable multi-trackers had an integrated mixer, so the 10-track bounce would be possible too, all from within one machine. Here’s how you’d do it:

- Record on tracks 1, 2 and 3, and while mixing these down to record on track 4 add a live performance. So that’s effectively four separate tracks into one mono track.

- Record more stuff, then bounce tracks 1, 2 and a live input onto track 3 (three separate tracks into one mono track).

- Record more stuff then bounce track 1 and a live track to track 2 (two separate tracks into one mono track).

- Now you’ve one remaining track to record on. The track count across four physical track totals: 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 10.

Tascam 238 8-track cassette recorder

Just about all four-track tape decks would have noise reduction on-board. I used a Fostex 250 which had Dolby C but Tascam and Yamaha models featured an alternative by dBx. Amazingly, Tascam even went so far as to produce an eight-track model that used the Compact Cassette.

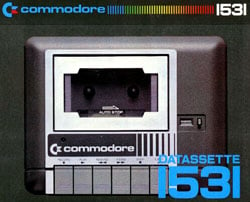

Commodore Datasette kept alongside many a Pet

There were other applications for musicians too, as tape backup of synth sounds, sequences and drum machine patterns could be saved on tape. There's more on this right here.

And it wasn’t just musicians who were doing this. The cassette tape was the backup medium for many microcomputer owners in the 1970s and early 1980s. It could handle data rates of 2kbs, notching up about 660KB per side on a C-90, close to a 3.5in HD floppy disk.

Getting duped

Philips in-car cassette player advertisement from 1971

Analogue cassettes in cars did a lot better than the

Digital Compact Cassette

Source: Philips Company Archives

There was a fair bit of ground to cover before the prevalence of Dolby on prerecorded cassettes became an issue. The winning combination of portable radio and compact cassette recorder emerged fairly early on when Philips produced its own model, the racily named Type 22RL962, in 1966. It followed this up in with a stereo model, the EL 3312, about a year later. In 1968 the RN582 car radio cassette made its debut. Other manufacturers were claiming firsts on various fronts as consumer audio products felt the benefit of transistorisation.

Music centres – all-in-one stereo systems with radio, turntable and cassette recorder – became commonplace in homes with audiophiles eschewing these in favour of hi-fi separates where the cassette ‘deck’ was manufactured with quality as the number-one aim, rather than affordability or portability.

With these various combinations gaining popularity through the mid-1970s and beyond, the issue of copying became a bone of contention. People were sharing their vinyl records and taping them. Records could be borrowed from public libraries and cassette copies made. It was stealing. In other territories, developing countries in particular, where the Compact Cassette was more widespread than other forms of recorded media, the sale of pirate copies was commonplace.

Friendly BPI campaign – not everyone agreed with its message

While these overseas activities were beyond the reach of Western record companies, back home in Blighty, the BPI led a campaign to bring our music-ripping nation to book in the 1980s. The slogan "Home Taping Is Killing Music" was the industry’s browbeating missive to counter its fears that record sales would suffer due as a consequence.

Yet for the consumer, taping and sharing music was a way of discovering new bands and for many artists, this was acceptable because it was a way of growing their fan base. Fans that would soon enough buy their records and probably attend concerts with their mates.

The pros and cons of copying is an argument that still rages to this day. Certainly, Philips had no idea that the introduction of a dictation machine some two decades earlier would lead to such strife.

There were other reasons for recording vinyl which many felt were perfectly legitimate. Why not have a recording of the album you bought to play in the car? What about those favourite tracks of yours? Mix tapes for parties, romance and just sheer pleasure were recordings young and old alike would painstakingly piece together from their music collections, manually taping each track. And it wasn’t just for use in the car.

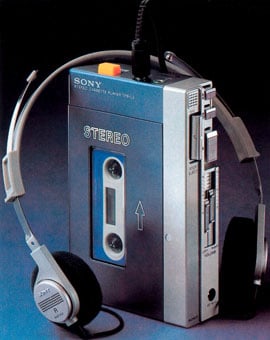

Sony's Walkman used headphones and made it all personal

The Sony Walkman was a game changer for the Compact Cassette, arriving in 1979, and sported headphones rather than a loudspeaker. Its portability triggered a craze for music on the move. A distinctive feature of Walkmans and its me-too rivals that followed was that they were playback only. Recording Walkmans were offered for more professional uses and became popular with reporters. Other brands would follow suit with some even including a radio in this portable package.

Twin cassette decks appeared too, enabling tape-to-tape copying and dubbing with some consumer models featuring a Walkman-style player that would dock in the main unit that contained the recorder. The genie was definitely out of the bottle as far as making copies of recordings was concerned.

It’s worth remembering that we’re well and truly in the analogue domain here and so tape copying would always bring with it the baggage of tape hiss. Unlike the world of digital audio that we are immersed in today, the signal would degrade markedly with repeated tape copying generations beyond the original source.

Even so, as the cassette recorder evolved, so did the media with chromium dioxide and eventually Type IV (metal) tapes offering improved dynamic range and frequency response. These new formulations required different bias frequencies which led to additions to the Compact Cassette standard. Hence, switches for ferric, chromium dioxide and metal that would adorn many Compact Cassette machines would all conform to their respective equalisation settings.

Going digital

Other improvements appeared such as Dolby C noise reduction along with HX Pro, the latter tweaked the bias for a "headroom extension" (increasing the dynamic range) but neither really took off. However, the enhancements in recording media and signal processing, together with the arrival of the Compact Disc, did mean that home recording was sounding better than ever. Another way of looking at it, though, was that this pristine digital disc format revealed the shortcomings in using cassette tape, particularly in its high-frequency range.

As vinyl took a backseat and the crackle-free fidelity of the Compact Disc made its presence felt, it was inevitable that a consumer digital recording format would emerge. Recording studios had been blessed with a number of options for some time, none affordable for the mass market.

See, I told you it was big: Philips DCC 900 digital compact cassette deck

While Sony pondered on what would become the MiniDisc, Philips hit upon the idea of the Digital Compact Cassette (DCC). It would support a resolution up to 18 bits and sample rates of 32kHz, 44.1kHz and 48kHz. The killer feature would be backwards compatibility with your existing analogue cassette library. The technical aspects of DCC are discussed in more detail here.

DCC worked, but the massive DCC 900 machine that was debuted wasn’t the in-car digital tape system that the dealers had been promised. That would come later along with the portable DCC 170 ‘walkman’. DCC failed not because it was technically lacking – it allowed track naming and sounded superior to early Sony MiniDisc models – but because the idea of fast-forward and rewinding tape was now dated in the minds of its target market.

Digital Compact Cassette (DCC) with an analogue cassette beneath it

These people were used to the instant access convenience of CD and were looking for the same in a digital recorder. Sony’s MiniDisc delivered this and won the day as a consumer digital recording format. That is until Apple’s iPod and iTunes promoted the concept of rip, mix and burn.

Fast-forward, eject

Philips claims that about three billion Compact Cassettes were sold in the 25 years between 1963 and 1988. Beyond that period, other formats ate away at sales: in the US alone, sales of Musicassettes dropped from about 450 million in 1990 to just over quarter of a million in 2007, according to Billboard. Yes, you can still buy tapes and cassette recorders remain in production too, but the choice is fairly limited.

Many of us continue to encounter cassette recorders as the equipment endures in car stereos, decades-old boom boxes that never die, and fully functioning hi-fi separates that we haven't the heart to bin. Whether this equipment is ever used to play a cassette is another matter, but I confess to owning a DCC 900 (I couldn't afford a DAT) and fire it up from time to time for both analogue and digital playback. It’s still going strong.

I’ve had the pleasure of finding out what the best of breed in the today's cassette recorder market has to offer, having just reviewed Tascam’s CD-A750. It’s a beast designed for studio use featuring balanced analogue XLR connectivity. On this model, alongside the Compact Cassette deck, is another Philips technology with Lou Ottens' fingermarks on it, the Compact Disc.

Thank you Mr Ottens, and happy birthday, Compact Cassette. ®