Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/08/23/acorn_electron_history_at_30/

Acorn’s would-be ZX Spectrum killer, the Electron, is 30

The story of the BBC Micro Junior

Posted in Personal Tech, 23rd August 2013 09:04 GMT

Archaeologic The Sinclair Spectrum made the Acorn Electron inevitable.

In June 1982, less than two months after Sinclair had unveiled the Spectrum - which had still not shipped, of course, even though Sinclair had promised the first Spectrums would be in punters’ hands by the end of May - Acorn co-founder Hermann Hauser was heard talking about a rival machine. He candidly told Popular Computing Weekly that Acorn’s next machine would debut in the third quarter of the year, taking the fight straight to the company’s nemesis.

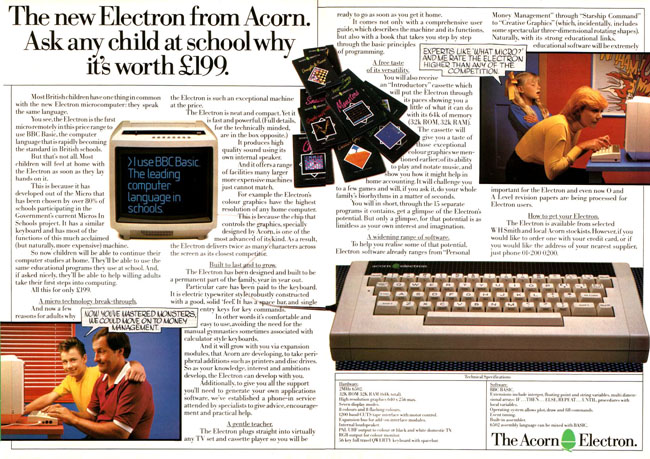

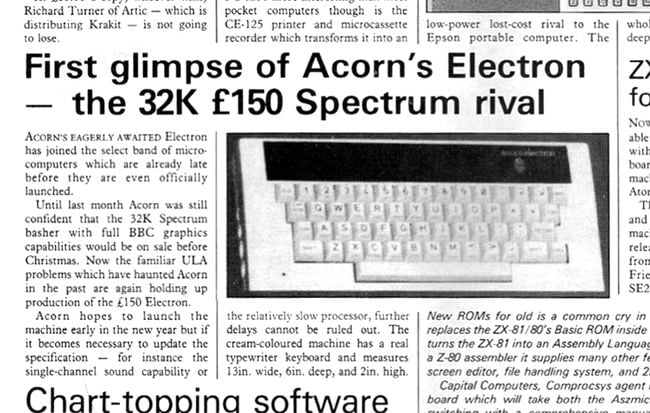

Sinclair priced the 48KB Spectrum at £175. So the 32KB RAM, 32KB ROM new Acorn machine - which “will probably be called the Electron”, the paper reported - would set punters back between £120 and £150, Hauser suggested. And it would offer higher resolution colour graphics than the Sinclair computer too and, crucially, be compatible with BBC Micro software.

Acorn’s would-be Spectrum killer: the Electron

Hauser’s revelation came in response to a question concerning the Spectrum’s potential to undermine sales of Acorn’s cash cow, the BBC Micro, which had gone on sale just six months previously, at the end of 1981, and was actually now more expensive than it had been when it debuted. Hauser, of course, laughed off the suggestion, but his comments suggest Acorn was very aware of booming sales in the lower reaches of the market, a segment the pricey BBC machine, even in its cut-down Model A form, couldn’t reach.

Yet not everyone desiring a cut-price micro wanted a typical Sinclair lowest common denominator offering. Some eight months after Hauser had spilled the beans to Popular Computing Weekly, and with the Spectrum by now firmly established, Acorn’s other founder, Chris Curry, claimed: “We never expected the BBC machine to compete with the Spectrum first time round, but people who want something better than the Spectrum are turning to the BBC... The number of machines being bought by individuals for use in the home has surprised us.”

As the hints Hauser dropped in June 1982 show, the solution was obvious: produce an even cheaper machine than the BBC Model A that would appeal not only to potential Spectrum buyers but also to people who were drawn to the cachet of the BBC Micro but couldn’t or wouldn’t justify spending up to £399 on a home computer - especially when you could buy a Sinclair machine for less than £100, a Vic-20 for not much more than that or, soon, a Dragon 32 for under £200. Even Acorn’s own Atom was still available, for £150.

The BBC Micro, but cheaper

“Once the BBC Micro was launched, there was a feeling that the machine was great but that it was a bit expensive, and that there was a big market out there comprising people who would buy machines if only they were a bit cheaper,” remembers Steve Furber, the one-time senior Acorn techie who co-designed the BBC Micro and is now ICL Professor of Computer Engineering at the University of Manchester. “And Chris Curry was very sensitive to what Clive Sinclair was doing, for historical reasons.”

Indeed, when the Electron finally debuted in the summer of 1983, Curry was unequivocal about the machine’s relationship with the Spectrum: “The Electron is designed to compete with the Spectrum. The idea is to get the starting price very low, but not preclude expansion in the long term. It runs the same Basic as the BBC machine. We anticipate it having just an extension bus, and the extension bus will have modules plugged into it to give you whatever interfaces you want.”

The Electron, then, would be a “miniaturised” BBC machine in Spectrum clothes - in 1982 it was being reported that the Electron would sport a calculator-style keyboard, and would have single-key Basic command entry - and aimed at the cost-conscious consumer.

Steve Furber and his fellow engineers in Acorn’s R&D team were initially less keen on the taking the fight to Sinclair with a cost-engineered ‘BBC Micro Junior’. “We were keener to move forward,” he recalls to The Register.

“We were not that enthusiastic about doing this cost-reduction exercise. But ultimately we were persuaded by Chris and by Hermann that there was a market.”

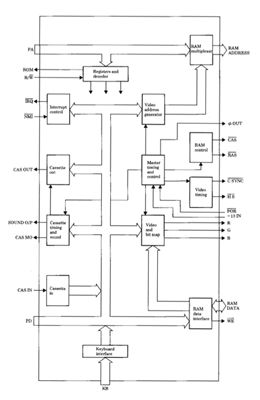

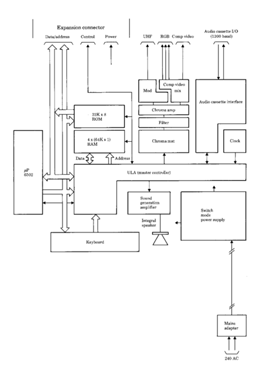

Central to cutting the cost of the new machine was reducing the chip count. In place of the BBC’s various ancillary logic chips, the Electron would employ a single Uncommitted Logic Array (ULA) chip, a trick Sinclair had employed in the ZX81 and Spectrum; the ZX80 had used off-the-shelf TTL parts. “That allowed us to take a machine which had 102 chips on the motherboard and reduce it to something like 12 or 14 chips,” says Furber, “basically an order of magnitude reduction in the complexity of the motherboard.”

One chip to rule them all

Out went the BBC’s 6845 video controller, memory controller, serial IO control and timer chips, all replicated to a greater or lesser extent by the ULA’s all-in-one circuitry. “We could pretty much fit all the functionality of the Beeb [BBC Micro] into a ULA with the exception of the microprocessor and the memory,” says Furber.

He was tasked with designing this custom chip, but it wasn’t the only cost-reducing technology the new machine would feature. By the time work began on the Electron, commodity DRAM had gone from the 16Kbit chips used in the BBC Micro to 64Kbit parts, so another obvious way to make the machine cheaper was to take advantage of this higher density memory.

“The problem was, of course, that the BBC Micro architecture only had 32KB, so if you were using 64Kb DRAM chips, you’d need four of them to give you 32KB and then you’d have to be double-accessing them for every byte you wanted,” Furber says. “That basically drove the Electron architecture: the recognition that for cost reasons we had to go that way. There were inevitable performance compromises as a result of that. We couldn’t do double-access at 4MHz - the memory wasn’t fast enough for that - so we had to accept we were going to have to live with lower total memory bandwidth, which we didn’t like.”

But for the ULA, the Electron was done by the end of 1982, and was seen for the first time in the December issue of Your Computer

As 1982 drew to a close, Hauser’s original launch window had long since closed yet the Electron seemed no closer to a launch. Pictures of the machine leaked to the press, revealing a machine identical to the one that would finally be revealed in August 1983. Acorn couldn’t keep the new machine’s existence a secret any longer. A company spokesman told Popular Computing Weekly in November 1982 that the new machine was “ready apart from the ULAs” but in any case wouldn’t be made available “until we have built up substantial stocks”.

Chris Curry made the same pledge in January 1983. The machine would launch in March 1983 “for sure”, he promised. It was a pledge that would come to haunt the company in the months following the Electron’s debut.

Designing the ULA

Curry and other Acorn staff were so confident because work on the broad design of the Electron was complete. By this point, the case and mechanical design had been done and so had the motherboard - they’re all stamped “Copyright 1982”, after all, as was the label on the base of the machine. But getting the ULA right continued to delay the machine’s release.

The delay was not induced, reveals Furber, by the complexity of a part integrating so much of the BBC Micro’s functionality, or of specific failings in ULA maker Ferranti’s production process, but rather trouble with the chip’s video circuitry. “On the BBC Micro we had problems with the video processor overheating, but we understood why that was the case in great detail,” he says. “So I was extremely careful when designing the Electron ULA to avoid a repeat of those problems. I completely redesigned how the high-speed end of the video worked to make sure everything was compatible with Ferranti’s ULA technology, and yet we still had problems with the high-resolution modes breaking up.”

Setting the Electron’s graphics to the two-colour 640 x 256 Mode 0 - a mode which took up 20KB of the computer’s 32KB memory, but was used by applications and games - caused pixels to twinkle: to change colour at random, essentially sprinkling the screen with noise. Back and forth between Acorn in Cambridge and Ferranti in Oldham went design tweaks and fresh sample ULAs as Furber and the Ferranti engineers attempted to pin down what was causing the problem.

“We had the usual kind of stand-off: Ferranti were convinced this was a design fault, and I was completely confident it wasn’t because we’d had all that trouble with the Beeb, and so I’d made sure everything was in spec. I don’t remember how many times we went around the loop. It was made a bit easier because Ferranti were in Oldham so we were not having to communicate half way round the world to tweak these problems but we did end up a bit of a technical disagreement between their engineers and our engineers, in particular me.

“In the end I convinced myself the voltage swing was too low on these ULA circuits and what we were seeing was on-chip noise being picked up. In the end, when we changed the voltage regulator on the ULA, increasing the voltage swing by about 50 per cent, the problem went away.”

Preparing to launch

Meanwhile, Acorn was busily talking up the new machine. Curry hinted that the upcoming Electron would not only help Acorn address the Sinclair end of the market, but allow it to pitch the BBC even more up-market than it had done so to date. “As the Electron comes in at the low-cost end of the market, so the BBC will move up with a range of business software and second processors.”

That was in February 1983. By now it was public knowledge that the Electron was on its way and that the new computer would run BBC Basic - no great surprise given the growing library of BASIC software and Acorn’s desire to sell the Electron on the coat tails of the premium machine. It was also known that it would lack the BBC’s graphics Mode 7, the Teletext mode demanded by BBC Engineering during the establishment of the BBC Microcomputer’s early specifications and which required a separate chip, the SAA5050 - this was dropped for cost reasons.

Acorn may thought that few punters cared about Mode 7, but the Telextext-compatible mode had one key advantage: it used only 1KB of the machine’s 32KB of memory, leaving more for the user than other BBC Micro graphics modes did. Without Mode 7, the Electron had to boot into Mode 6, which presented 40 x 24 characters and grabbed 8KB of RAM - a quarter of the amount installed in the machine. Other graphics modes, such as the 640 x 256 Mode 0 or the 320 x 256 - but more colourful - Mode 1 took up no less than 20KB, leaving very little left for the owner’s code.

Previously said to sport only a TV output and a cassette interface, the Electron was now known to incorporate a composite-video and monochrome monitor ports and an expansion bus edge connector. All the other BBC ports were gone, stripped out to save money and to preserve the exclusivity of the pricier machine, although Acorn planned to offer some of them as plug-on adaptors for the Electron’s expansion bus.

“Because of the way we have designed things it is particularly easy for us to bring out a machine for a particular market,” Curry told Practical Computing back in the day. “We can both spread them out and add more facilities, or we can prune them down dramatically to produce a much cheaper machine.”

Price war

Curry reiterated the price. “The standard 32KB model will cost £150 excluding VAT. There is no compromise on quality either - the keyboard, for example, is the same as the one on the BBC,” he told Popular Computing Weekly.

Curry and co. were certainly bullishly confident. During the spring of 1983, Sinclair fired a broadside against his nearest rivals - the Dragon, Oric, Camputers, Atari and Commodore - by lowering the prices of the ZX81 and the Spectrum: the 16KB Speccy could now be had for less than £100. Most of his competitors responded - Commodore, for instance, by boxing together its ageing Vic-20 and the machine’s proprietary tape deck. Curry, however, waved such changes away as fear of the imminent arrival of the Electron.

Except, of course, that he had stated the machine would launch in March, and it hadn’t. Instead, at the end of May, Acorn said the launch would take place at the end of August. A sensible timeframe, you might think: bypass the quiet summer, and focus on the upcoming crucial Christmas sales period. But back in 1983, the received wisdom had become one of ‘if you ship it, punters will buy it’, leading some observers to wonder what Acorn was up to.

In part, the company may have been attempting to run down stocks of the BBC Model A, a machine Acorn claimed it had now stopped making because “nearly all orders now are for the BBC Model B”, though it insisted the decision to end production had not been prompted by the imminent arrival of the Electron. Even so, Acorn didn’t formally discontinue the Model A, a machine not quite as good as the Model B, until 1 September, 1984.

Originally expected to be the most popular BBC micro because of the much higher price of the Model B, the Model A had in fact languished in comparison as well-heeled, aspirational buyers - or simply folk with sufficiently pushy offspring - opted to pay the extra cash for the functionally complete model. Yet the A still wasn’t cheap enough to compete with the Sinclair machines and other lower price rivals. That was the Electron’s planned role.

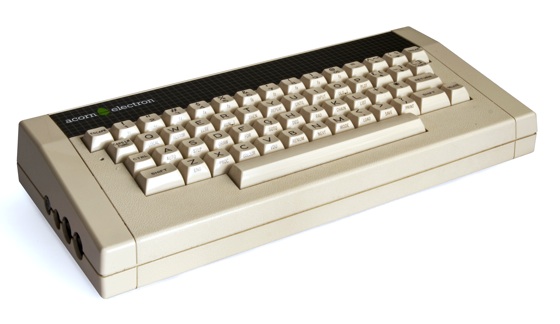

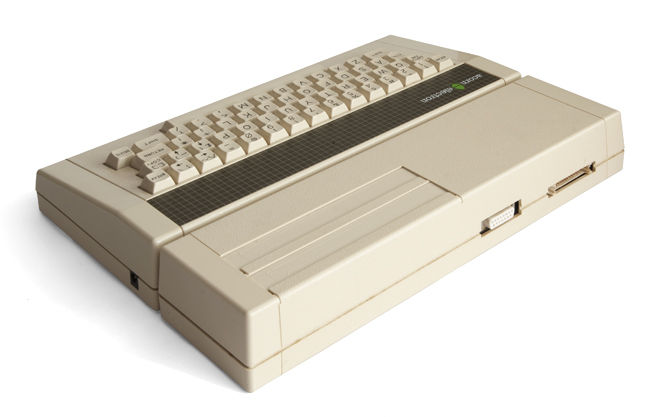

The launch

A full year on from the release window Hermann Hauser had first let slip in June 1982, the Electron was launched, at the 1983 Acorn User Exhibition, held that year in London’s Cunard Hotel in Hammersmith on the 25 August. Potential Electron buyers would have been pleased to see many an add-on for the new machine on show too. What they saw from Acorn was a cream-coloured unit closer in looks, perhaps, to the Acorn Atom than the BBC Micro. The casing was styled by long-time Acorn collaborator and industrial designer Cambridge Product Design’s Allen Boothroyd, who had previously designed the Acorn Atom and the BBC Micro cases. Inside was a 6502A processor running at 2MHz (when accessing ROM, slower when touching RAM) and hooked up to the aforementioned four 64Kbit Ram chips, two 16KB ROMs and Steve Furber’s monumental ULA.

At the launch, Hauser boasted: “[The ULA] is by far the largest custom chip anyone has put in a micro, with over 2400 gates.” The chip would require 68 IO lines and measure 30 x 30mm. It would be the largest chip on the Electron’s motherboard, bigger even than the computer’s 6502 processor.

The Electron’s ULA up close

Source: Darren Harris

A secondary concern the ULA was able to address - or at least one Acorn executives seemed keen to talk up at the time - was piracy. During the early 1980s, a fair few knock-off Apple II machines appeared, almost all of them from the Far East. What made the Apple machine easy to clone was its big, clear motherboard layout and reliance on off-the-shelf chips. British micros had always been hard to copy because so much circuitry was hidden inside ULAs. “That is why Sinclair can be relatively safe with the ZX81,” Chris Curry said in 1982. “It is the perfect [computer] to copy in Taiwan, but for the fact it has ULAs in it.”

This was true too to a lesser extent of the BBC Micro, but Acorn seems to have been particularly keen to obscure as much of the Electron’s circuitry as possible. “I defy anyone to copy that chip,” Hauser said in August 1983.

No longer was the Electron set to ship for as little as £120 - it would now retail for £199. That was more than the 48KB Spectrum cost at launch and even more so now that Sinclair had cut its top-of-the range computer’s price to £129.95.

Thumbs-up from the pundits

Thanks to the Electron’s lack of Mode 7 and of many of the IO ports and slots found on the BBC, Acorn’s software arm, Acornsoft, said it was busily tweaking 12 of its most popular programs to make them fully compatible with the new machine. Acornsoft chief David Johnson-Davis said he expected it to be six months before the Electron’s software library was of a size to match that of the BBC. Johnson-Davis also made sure that two young programmers then quietly hard at work on a novel space trading game complete with fast 3D wireframe graphics were able to make their code run on the Electron as well as the BBC Micro. When Ian Bell and David Braben’s Elite went on sale the following year, on 21 September 1984, it ran on both machines.

By launch, Acorn had already begun seeding review machines with the press. The first write-ups appeared toward the end of August 1983, though these early evaluations were based on pre-production kit rather than shipping units, each machine with its own uniquely numbered - written on the top in marker pen - ULA chip. The major monthlies, with long lead times, didn’t get their reviews into print until September or October, but that wasn’t a problem as the Electron wasn’t going to go on sale until that time.

Early or late, the reviews were generally favourable. “The Electron gives the impression of being all keyboard. It has a satisfyingly solid feel to it and generally gives the impression of being a very classy product indeed,” enthused Steve Mann in Personal Computer World.

“We are told that the casing has withstood the rigours of the British Aerospace testing laboratories,” added Personal Computing Today without any hint of sarcasm or scepticism.

“Unlike certain other manufacturers, which let out a squawk and invalidate the guarantee if you even so much as think of reaching for a screwdriver, Acorn positively encourages users to delve about inside,” PCW’s Steve Mann noted gleefully. “The top of the case lifts off after removal of four screws and the ribbon cable that connects the keyboard simply unplugs... The board itself is beautifully laid out, with every component clearly labelled and plug-in connectors for the power lines and speaker leads.

Slow RAM

“It would appear that Acorn has been playing around with the Electron design right up until the moment it was launched — other review machines have apparently contained a single ROM chip in place of the BBC Micro's two, and have shown evidence of the odd patch on the board; PCW’s version contained the full complement of ROMs and every component appeared to be in its final position with not a patch in sight.”

However, speed was an issue, reviewers found, especially those used to the BBC Micro. Steve Furber’s ULA may have caused all the delays, but it was the choice of cheap, high density DRAM and its impact on the Electron’s performance that drew the most fire. “A major quirk of the Electron is the way RAM is organised. In the interests of economy, four 64Kb RAM chips have been used, but as these can only be read four bits at a time, memory access time is virtually doubled so that the Electron is dramatically slower than the BBC,” wrote Keith and Steven Brain in Popular Computing Weekly.

The Acorn Electron’s Plus 1 add-on pack

Source: Bilby

Putting the video sub-system into the ULA slowed down the graphics too “so that although many games designed for the BBC [Micro] will run on the Electron they proceed at less than half the speed, with very significant effects on their appeal” and thus “spoiling the ship for a ha’porth of tar”, the two Brains complained. Irritatingly for some game coders, the Electron’s ULA lacked the BBC’s ability to quickly scroll the screen sideways.

“In Modes 0, 1 and 2 the RAM access of the video part of the ULA is interleaved between the 6502A access. For 40μs out of 64 the processor is out of action,” explained Practical Computing’s Neville Maude. “In Mode 3 the processor is running full speed on alternate lines. In Modes 4, 5, and 6 [the CPU] runs at 1MHz all the time it accesses Ram. Hence a program taking ten seconds on the BBC in all modes can take on the Electron about 43 seconds in Modes 0, 1 and 2; about 34 seconds in Mode 3; and 20 seconds in Modes 4, 5 and 6.”

Integration of the sound chip functionality into the ULA limited the Electron to playing only a single sound and a single noise channel at a time, despite supporting multiple channels in its BASIC to maintain compatibility with BBC programs. “As with the Spectrum, the best that can be achieved is simple sound effects for games,” noted Steve Mann in PCW.

Critical mass

Yet for all the reduction in speed, so great was the BBC Micro’s lead over most of its rivals that the Electron could still shine. “If tested for speed using the usual benchmarks, the Electron runs about 30 to 40 per cent slower [than the BBC],” said Maude. “Arithmetical computations are the slowest but, since the BBC BASIC is so fast the Electron is still doing well.”

That didn’t stop him later grumbling that “the main program generally loads but then runs like an arthritic snail, about 2.0 to 4.3 times slower than it should”.

No BBC logo here

Source: Quagmire

Yet Personal Computing Today said that “compared with other machines - including the Commodore 64 - the speed is acceptable and the colour and resolution far superior”. And Personal Computer News’ Max Phillips reckoned that “relative to the competition, the Electron is delightfully quick”.

But though the Electron itself may have been pleasingly fast, the same couldn’t be said for Acorn’s ability to get machines out into the shops.

Back in February 1983, Acorn’s Chris Curry has revealed the Electron would be produced in Singapore. “One reason is that the duty on components in the UK is thoroughly unacceptable, notwithstanding the fact that overseas suppliers have to a certain extent adjusted their prices to take account of it,” he said when asked why a British firm was not handling the micro.

Ramping up manufacture

“But the main reason we will be manufacturing the Electron overseas is that we wanted to apply some fairly radical production techniques. We find there is less resistance to change in countries like Hong Kong and Singapore. They go straight in with capital expenditure on new equipment: automated component insertion tools, bonding equipment and the like. British companies find this difficult to do and there wasn't anyone in the UK who was already set up for it.

“We would obviously prefer to be manufacturing in the UK but the first run at least will be in Singapore.”

Curry concluded: “We will not do any advertising until we are completely confident that stocks are available. More than almost anyone else we have suffered in the past and problems of lack of product when the demand is high, and we’re not going to let it happen again.”

Acorn indicated early in September 1983, right after the Electron’s launch, that it hoped to sell 100,000 units of the new computer by February 1984, though by now the manufacturing of the machine had been contracted out to Astec in Malaysia. Nonetheless, a spokesman said the firm was hoping to start UK production in six weeks’ time. The manufacturer was rumoured to be AB Electronics in South Wales, and rumour became fact at the end of September when the partnership was formally confirmed.

“It is our intention to dominate the £200 price range with the electron in the same way as we have done in the £400 range with the BBC machine,” a company spokesman said at the time.

AB was reported to be gearing up to produce 100,000 Electrons, too. Handy, that, since by October, Acorn was claiming it had taken orders for more than 150,000 machines. That figure was, it was forced to admit, far bigger than it could cope with; it had no hope of satisfying demand.

Surging demand

“We are ramping up production, and we should reach our target of 25,000 machines a month [just] before Christmas,” an Acorn spokesman confessed.

The sums tell the story: at that rate of output, it was going to take Acorn more than six months to deal with the backlog let alone new orders received in the meantime. It was the early days of the BBC Micro all over again.

Retailer WH Smith was keen to offer the Electron but was able to stock just two of its London branches. “We’re having to disappoint customers,” said a spokeswoman for the newsagent at the time. “We are not able to supply demand. What we have has sold out, and while we are expecting more deliveries the amount will still be well below demand.”

Maybe that was just as well. As Popular Computing Weekly reported in early November, there was still no Electron-specific software to buy. By now it was clear that AB Electronics would not be ready to ship Electrons until the following year. Acorn quickly signed Hong Kong contract manufacturer Wongs, which said it would be able to tool up and start shipping machines by the end of November.

Acorn marketing manager Tom Hohenberg would many years later place the blame for the slow production ramp on Ferranti - later GEC Plessey - for failing to punch out sufficient working ULAs. Only one in ten worked, he claimed. No wonder Acorn brought in VLSI Technology, which would later fab the first ARM chip, to produce a CMOS version of the ULA during 1984.

By then, though, the bottom had dropped out of the UK home computer market. The boom was over. Unlike Dragon Data and Camputers, Acorn didn’t go under in 1984, but it struggled. “Whereas the trucks had been lined up at either end of the Wellingborough warehouse delivering and collecting machines before Christmas, after Christmas they were just delivering and the company ended up with £43 million of unsaleable stock,” said Hohenberg.

Acorn in extremis

At the height of 1980s micromania - just a month or so after the Electron launch - Acorn’s founders put ten per cent of the company’s privately held shares up for sale on the Unlisted Securities Market (USM). The price was set at a minimum of £1.20 a share, and with 11.24 million shares available to buy, the sale made millionaires of Chris Curry and Hermann Hauser, and helped pave the way for future expansion of the business. Acorn took the BBC Micro into the US market, and established a US subsidiary, Acorn Computer Corporation, at a cost of £2.5m. The rights issue allowed Acorn to acquire UK IT giant ICL’s school computing division and to put in place a plan to buy Torch Computers, a firm that made micros based on the BBC motherboard and which had launched in 1982 with Curry’s help.

But the US venture was a failure, costing the company £6m in the end. Acorn had aimed to take ten per cent of the US schools computing market but ultimately won “far less” than that, a company spokesman admitted at the time. During 1984, Acorn cut its losses and slashed the scale of its US operation by 80 per cent, leaving only an R&D facility and a “small office” to handle sales such as they were.

Acorn advertises the Electron... on telly. This ad cost £150,000 to make - ”a fortune in those days”, says former Acorn marketing manager Tom Hohenberg

Acorn then expected to sell 300,000 BBC Micros and Electrons over the Christmas 1984 period, but in the event only 200,000 were sold. Electron sales, in particular, were “not in the same league as Commodore or Sinclair” a spokesman admitted. As Steve Furber says now, the Electron was a “1983-specification machine not a 1984-specification machine”. In a bid to shift more Electrons, come January 1985 Acorn cut the micro’s price to £129, what Sinclair was then charging for the 48KB Spectrum Plus and a move investors feared would diminish Acorn’s profits even further.

Fortunes were turning. The six months to 31 December 1983 had netted Acorn record sales revenues totalling £40.4m, in turn yielding profits of £5.21m. A year later, that surplus had vanished, and the company lost £10.9m in the six months to 31 December 1984.

So investors turned away from Acorn shares. Early in February 1985, the value of the stock plunged to 23p, a fraction of the issue price, cutting the company’s value from £216m a year previously to £31m, and triggering the suspension of their sale. Trouble was brewing: only the week before, Acorn put in a temporary chief executive, Dr Alexander Reid, to handle the company’s day-to-day operations. Then it sacked 31 of its 450 workers and fired its financial advisor, Lazards, after disagreeing about how the company should be run in the future. Eleven of its 17 product distributors were culled, and the Torch takeover was canned.

Crisis point

A few weeks later, one of Acorn’s creditors, circuit board supplier Circuit Techniques sought and won a court order calling for the company to be wound up because Acorn had, CT claimed, been unable to pay bills totalling £19,000 issued since November 1984.

Enter the Italians. At the end of February 1985, Italian IT and office equipment firm Olivetti said it would pump £10.39m into Acorn in return for 49.3 per cent of the British company, in effect a controlling stake. Hauser and Curry would keep 20.1 per cent and 16.5 per cent, respectively, 36.5 per cent in total, and step away from running the company they had founded in 1978. A further 90 general job cuts would be made and the Acorn Business Computer (unveiled in July 1984) would be killed off before it even shipped. The Acorn Communicator, a proposed micro with an integrated phone, would never see light of day either - ditto the £3,500 to £8,000 Cambridge Workstations Acorn was planning to base on National Semiconductor’s 32-bit 16032 processor.

But the Electron, seen to be low on Olivetti’s list of priorities too, managed to hold on. “We will be continuing to sell the Electron this year and hopefully next year as well,” pledged Reid, still interim chief executive and, by the end of February, also company chairman. But it was clear that the company was simply selling off existing stocks of the micro - only if they shifted would more be made. “Whether we will go into production on the Electron again or not will depend on our sales level during the year,” he admitted.

Yet more redundancies followed, and by the early summer it was clear even Olivetti’s cash injection wasn’t medicine enough to revive the ailing Acorn. Acorn’s shares fell as low as 9p, though they gained a few pence soon after. At the end of June trading in them was suspended again. Reid stepped aside as interim chief exec to make way for Olivetti appointee Alex Umboldi.

July was a time of crisis for Acorn. It had expected a 40 per cent decline in sales, but the fall it experienced proved much worse as the uncertainty surrounding the company’s future compounded the existing downturn in consumer sales. Extra cash was desperately needed, and Acorn even pleaded with the BBC to reduce or postpone the royalties it paid to use the corporation's logo on the Model B and recently launched B+ machines - though not, of course, on the Electron. Proposals went back and forth between Acorn, its creditors, its merchant banks, Olivetti and its other major shareholders. Could the Italian company - or another rescuer - be persuaded to cough up a further £20m to save the business?

Road to recovery

It was willing to trade more capital for stock, but not as much as that. At the end of the month, it increased its stake in Acorn to 78.9 per cent by injecting a further £4m. Hermann Hauser and Chris Curry were left with with a combined stake of 14.5 per cent. The BBC agreed to waive £2m in owed licensing payments, and Acorn’s creditors kissed goodbye to some £7.9m they were owed by Acorn. Had the company crashed they would have got nothing. Creditors at least got £8.4m up front and £4.4m in loan stock. But by now 176 of Acorn’s 451 workers had lost their jobs.

The tsunami had subsided. “The cash injection was needed for the immediate survival of Acorn,” said Umboldi. “The financial position of Acorn is now stable.”

Source: No BBC logo here

Quagmire

So too was a deal with the creditors, Alexander Reid revealed. “Acorn is now stripped of the problems of the past.”

Acorn shares were soon back on the market. And, at the end of July, it launched what was to prove its most lasting legacy: the ARM chip. Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson had formally begun working on the processor in October 1983. It was Furber’s first major project after the Electron ULA was complete.

The Electron itself was still around, but two years on from its launch, it was getting harder to find as stocks dwindled and retailers refused to take more. Dixons had resorted to flogging it off for £100 with a bundled tape deck and five software packages. Indeed, by the end of September it had agreed to buy all of Acorn’s remaining unsold Electrons.

How much the retailer paid was never disclosed, but it amounted to less than it had cost Acorn to make them in the first place. The sale also marked the effective end of Acorn’s presence in the UK home computing market. The Electron was all but dead, and the 64KB BBC B+ and its newly announced 128KB sibling were priced at £469 and £499 - well above what most ordinary buyers were willing to pay - had they been keen to buy anything at all. ®

Special thanks to Professor Steve Furber for the invaluable insights he gave into the Electron ULA design work