Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/07/26/quatermass_iv/

Signing out of a broken Britain: The final Quatermass serial

Ley-ing it on thick with alien beams and hippie dreams

Posted in Personal Tech, 26th July 2013 09:06 GMT

Quatermass at 60 Nigel Kneale was one of the best British writers of the past 50 years, but thanks to enduring British snobbishness about both TV and stories of the imagination, the name is met with blank looks today.

Luvvies and critics have never taken to Kneale's Professor Quatermass character - and perhaps more people will recognise the name Rod Serling than Kneale even though Quatermass preceded Serling’s Twilight Zone by several years.

The original Quatermass TV series turns 60 this year and we’ve already given it some a loving reconsideration at El Reg.

Last year, Verity Stob gave a bird’s eye view. But there’s a part missing: Kneale’s final Quatermass instalment, which ended the saga and killed off the eponymous hero. The Thames TV four-parter from 1979 is today described as regularly a “cult classic” – an ambiguous term often used to damn material that only fanboys or stoned students can guffaw to.

So is the final Quatermass up to much? Is it worthy of the ‘brand’, which by the 1960s meant subtle, grown-up entertainment? Let’s have a look.

John Mills as Professor Bernard Quatermass

The Quatermass Experiment was broadcast while rationing-era Brits bought their first TV sets: 60 guineas for a 14-inch GEC in 1952. Kneale wrote entertainment for adults - “we didn’t get the kids,” he cheerfully admitted - that captivated a mass audience.

Kneale combined horror and science fiction to give invasion literature a new twist. His predecessors, such as HG Wells’ War of the Worlds, were really updates of the Western genre, only where the good guys wear white, and the bad guys wear green slime. It was pretty clear who was the enemy. And it was equally clear what needed to be done with them.

The Quatermass Experiment pulled the rug out from under this approach with a typically English bit of improvisation. The aliens had been here, on our world, before, and implanted memories into early humans. As a result, we were no longer certain quite what was a genuine human thought or instinct, and what might be a response to alien conditioning.

So, we couldn’t trust each other and the heroic individual had ceased to exist – he couldn’t be relied upon to save the day. Instead of John Wayne riding in on a horse, there was a more recognisably British figure, Professor Bernard Quatermass, who reasoned with and outwitted the aliens.

Broken Britain

In telling this original story, the technical limitations of the time - The Quatermass Experiment was filmed live, so the fly trapped inside the camera is still trapped in the prints today - and the meagre BBC budgets were turned into an advantage. The horror was off-screen and so implied, giving the films an atmospheric quality that was deeply unsettling. Alongside Kneale’s crisp and witty writing, it made for great grown-up TV. And it emptied the streets.

Many horror and sci-fi serials were inspired by The Quatermass Experiment – but without much of the dread and menace evoked by Kneale’s series. These are genres are routinely written for kids. Even the revived Doctor Who, which has had moments of great writing and imagination, routinely falls back on get-out-of-jail-free plot devices - such as "Timey Wimey" things, in the jargon. The TARDIS-dwelling hero is suited and booted for export as a kind of camp Jesus Christ; the idiot Englishman; Jeeves with a Gadget Belt; or Dr Raj with a time machine.

The Quatermass Experiment by contrast was using speculative fiction to tell a ripping yarn of paranoia and ageing, while questioning the foundations of authoritarianism, and it did so without the preachiness that suffocated British TV drama.

Never trust hippies: Planet People and their emerging leader, Kickalong (Ralph Arliss)

Outside the Quatermass serials, Kneale continued to produce challenging and original writing backed by a BBC willing to take risks. In his satirical 1968 drama The Year of the Sex Olympics, a United Nations plan to pacify the population by beaming a stupefying mix of live pornography and reality TV – until most are culled at the age of 28 – has been put into effect.

Mary Whitehouse unsuccessfully lobbied to stop its transmission. The world of Big Brother game shows and the internet isn’t so far away. You can see a 20-minute clip here on filmmaker Adam Curtis’ blog.

Kneale subsequently tackled ageing and the supernatural, again using his hallmark (as Verity Stob put it) “to pile up small individually plausible details to build an implausible whole”. So as he turned his hand to the final Quatermass serial, simply titled Quatermass, there was plenty to live up to.

Updating the professor

“It was written in 1972 and it was about the 1960s really,” said Kneale of the final instalment. The BBC had commissioned and announced the series - as "Quatermass IV" - but Kneale and the corporation parted ways. Filming didn’t begin until 1978 after Thames’ drama subsidiary, Euston Films - run by Doctor Who’s first producer Verity Lambert - took up the project, spun it into four one-hour episodes and a movie option, and assigned it a hefty - for its time - £1.25m budget. John Mills was a heavyweight choice as the professor.

Joe Kapp (Simon MacCorkindale) struggles with faith in the face of grief

In Kneale’s final vision, a grey and violently dysfunctional urban Britain faces breakdown, with feral gangs, state-sponsored bloodletting, corporate contract police, and rolling power cuts. An eschatological youth cult called the Planet People roams the countryside, convinced that they’re about to be transported to another planet. While Prof Quatermass is looking for his missing granddaughter, the Planet People begin to disappear in large numbers, and we learn large youth gatherings all over the world are also disappearing.

Terminal decline

Kneale drew deep on preoccupations familiar in the 1970s. The Baader Meinhof gang, the 1973 oil crisis and the accompanying three-day week aren’t obvious inspirations. There are also echoes of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and The Exorcist. The Planet People were initially modelled on the hippies, but Kneale was also inspired by Charles Manson’s Family. They’re really a full-on doomsday cult – which the world hadn’t yet seen in 1973: the Jonestown mass suicide took place while Quatermass was in post-production, the Heaven’s Gate Cult mass suicide was in 1997 and evangelical rapture belief is... ongoing.

Kneale suffered more than his fair share of cancelled projects in the 1970s, and must have grown weary of these, for the final Quatermass gets the weight of his own preoccupations. What might have been grown into fully fledged plays are incorporated into the four-hour series.

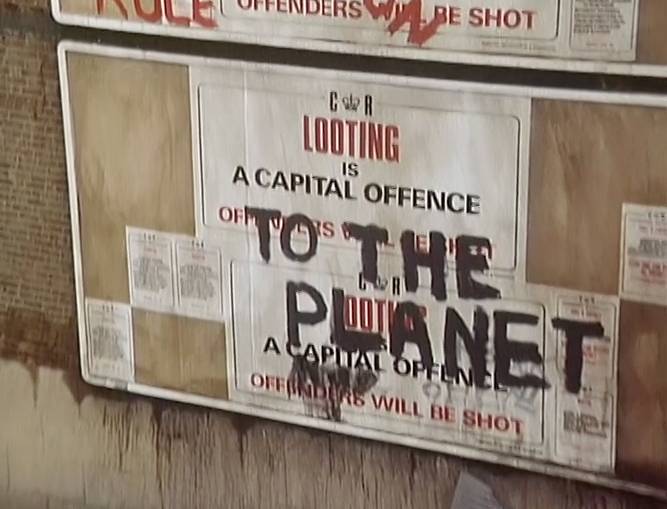

Britain through a windscreen: "Kill Science. Kill HM the King"

The satirical edge is sharper than ever. The utopian British bureaucrat – who thinks the Planet People are onto something, and can’t believe aliens would do anything beastly to us – also gets some fine lines:

“I’m just young enough to understand what the kids instinctively feel,” he tells Prof Quatermass.

“The planet?” asks the Professor.

“Yes!”

You don’t have to go far to find wide-eyed utopian bureuacrats in Whitehall, desperate to the down with da’ kids.

Kneale doesn’t spare TV culture in his programme, either. “But Tittetty Bumpety is what they used to call a family show!” cries a mincing TV producer as his live broadcast is commandeered for an Anglo-American backchannel. The whole grotesque sequence – a Pan’s People dance troupe are doing something figurative with a giant inflatable banana – will leave you speechless.

“It’s the only thing anyone watches any more!” Family entertainment, Tittety Bumpety

Keale’s fascination with ageing is expressed in a spooky and claustrophobic section where Prof Quatermass discovers every pensionable cockney character actor living underground in the same cellar – including, naturally, Gretchen Franklin (Ethel in Eastenders).

Not many 1970s film or TV completely avoided the modish production tricks of the era. Quatermass has a few montages and some sudden zooms of the kind that make Nic Roeg’s films unwatchable, but it largely escaped unscathed. The rasping electronic soundtrack, on the other hand, is often overpowering. While the score itself isn’t too bad - you can see what composers Rowley and Wilkinson were after at times, for example with the pizzicato as Kapp returns to his family home to find it destroyed - more subtle instruments would have been highly effective.

It was certainly a big-budget affair. Kneale professed he was surprised and pleased with the results: far more money was spent by Euston Films than originally envisaged by the BBC five years earlier. Much of it was shot outdoors, two large radio telescopes were constructed, and there are some impressive urban sequences. There’s a great panning shot of the professor's car as it trundles down a concrete ramp into a gloomy London with its skyline punctuated by tower blocks – the only things on the road are corpses.

Space Commander Travis makes a cameo as a pay cop

On the other hand, Equity pay rates ensure that we only ever see about 17 Planet People in the series, even as the hippies become a mass movement with "thousands" turning up to a gathering.

Mills is excellent as the weary Professor Quatermass, although the late Simon Charles Pendered MacCorkindale makes for perhaps the most gentile Jewish scientist ever portrayed on the screen.

Quatermass drew a decade of dystopian TV drama – Doomwatch, The Survivors, The Omega Factor – and the franchise to a close in fine style. Kneale would briefly pen a few of scenes of backstory for an opportunistic BBC radio documentary about Quatermass, scenes that he later disowned. And that was that.

Pensioners are forced to live underground in the final Quatermass. Note the portrait of King Charles III

The Quatermass Conclusion

What had made Quatermass so gripping? Kneale’s sure hand must have been a factor, his storytelling giving the series both a sense of dread and impeccable pacing. But Kneale also credited the audience. It was willing to indulge the programme makers.

“You had an audience that prepared to co-operate, that already was halfway imagining things that they couldn't quite see perhaps. I think now we've got a much lazier audience, certainly an audience that demands, and has been given by every Spielberg epic, high-gloss definition without, very often, much content,” he told Andrew Pixley in an interview with fanzine Timescreen.

Now the audience expects it for free.

The Professor gets filthy, again

Thanks to Kneale’s supporters – at the BFI, which has reissued some of the original broadcasts and both The Year of the Sex Olympics and The Stone Tape on DVD, and novelist Mark Gatiss - he’s belatedly received a critical revival. It’s long overdue. As Gatiss points out, more lustrous names such as Dennis Potter readily fill the posh papers, but writers of sci-fi and horror don’t. In contrast to Potter, once Kneale realised he might be repeating the formula, he knocked it on the head. Catch them all. ®