Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/07/24/feature_quatermass_and_the_pit/

Mars, bringer of WAR: Quatermass and the Pit

Britain’s arch boffin battles our erstwhile Martian overlords

Posted in Personal Tech, 24th July 2013 07:59 GMT

Quatermass at 60 “When I wrote the Quatermass stories, I couldn’t help drawing on the forces and the fears that affected people in the 1950s,” wrote Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale in 1996.

His inspiration for Professor Bernard Quatermass’ third appearance on television had been the Notting Hill race riots that struck the London suburb during the summer of 1955. The almost tribal conflict that took place back then - and which would flare up time and again throughout the following 40 years - caused the writer to ponder the causes of such unrestrained aggression.

“And men asked,” to quote the opening narration of the 1958 serial Quatermass and the Pit, “why should this be?”

So did Kneale, and why especially in a country considered as civilised and as on the up as late 1950s Britain thought itself to be. The economic shocks of the 1970s were more than a decade and a half away, and Britons back then “never had it so good”, as Prime Minister Harold Macmillan would insist in 1957. It struck Kneale that racial conflict and violence must be a very deep part of the human condition that it could explode through to the surface even in prosperous times.

“The last adventure, which I called Quatermass and the Pit, went way past the concerns of the time and into an ancient and diabolical race memory,” said Kneale in 1996. “It sought to explain man’s savagery and intolerance by way of images that had been throbbing away in the human brain since it first developed. Racial unrest, violence and purges were certainly with us in the 1950s, and I tried to speculate on where they first came from.”

Working in harmony: labourers black and white together discover the secret of their common human ancestry

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

In Kneale’s imagination, the cause of all this conflict went back to the Dawn of Humankind. It was rooted not merely in our evolutionary past but arose through a direct result of the manipulation of our infant species by another race of beings and of the cultural imprimatur they left behind on our genetic heritage.

And this, suggested Kneale, was the source of all human conflict. Britain may have been booming, but the privations arising from World War II had not been forgotten, nor the austerity years that followed it. The Suez Crisis had shamed Britain in 1956, only three years after Britain’s involvement in the Korean War came to an end. Both were fights explicitly associated with the Cold War simmering between the Western nations and the Soviet Bloc.

Indeed, it’s the Cold War stand-off that brings Britain’s best-known rocket scientist, Professor Bernard Quatermass, into the story when he is called upon by the War Office - it wouldn’t become the Ministry of Defence until 1964 - to advise on the siting of nuclear weapons in space and on the Moon.

Boffin and Breen: Quatermass and his military adversary ponder the pit’s portents

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

As the voice of enlightened scientific rationality, Quatermass naturally disapproves. His stance pitches him against Colonel Breen, an exemplar of the new military thinking: deterrent not détente. And, indeed, against the prevailing view of Whitehall, which wants Breen to take over the management of Quatermass’ British Rocket Group and redirect its efforts toward military applications of rocketry.

“The setting up of permanent bases on the Moon and possibly Mars also is a certainty in the next five to seven years. Those bases will be military ones. The present state of world politics leaves no doubt about that,” the Colonel warns.

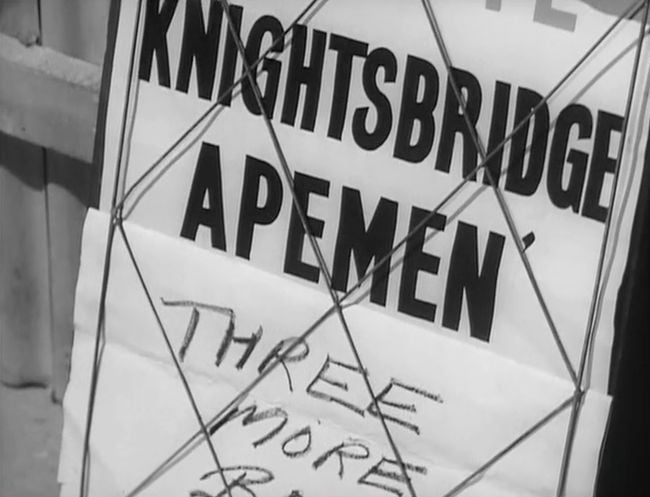

Furious, the professor goes off in a huff and into the path of Canadian anthropologist Matthew Roney. Roney is keen to tap Quatermass’ ministry connections when his work recovering humanoid fossils discovered under a Knightsbridge building site reveals what is first thought to be an unexploded German bomb buried since World War II.

Apemen found in Knightsbridge - and we don’t mean Harrods customers

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

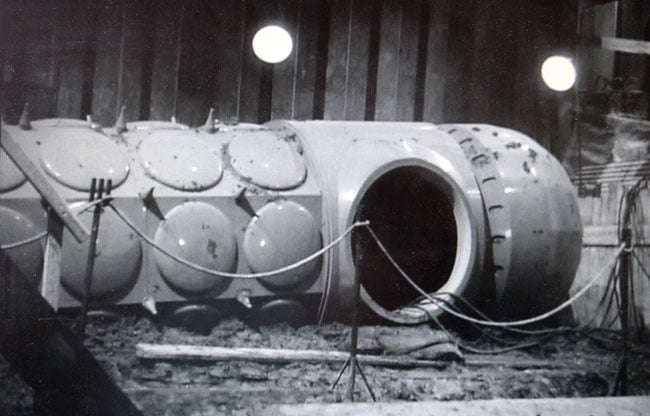

It’s a bombshell to be sure: but not rusting Nazi ordnance. Instead, it is revealed to be a crashed space capsule in which Quatermass discovers the preserved remains of what he guesses to be a Martian crew. They’re all small, green and have three legs - what else could they be? Quatermass knows his Wells. And Mars is, after all, the “Bringer of War”.

‘The chances of anything coming from Mars are a million to one’

The fact that an ‘apeman’ skull is found inside too reveals that the “earliest known true hominid” fossils, already seen to be from a higher branch of the evolutionary tree than humanity’s contemporary forebears should have been and literally millions of years ahead of their time, travelled to Earth in the same ship.

It’s a dramatic enough story as it is, but Kneale takes it further, working in theories and ideas then coming into vogue, most notably the concept of ‘race memories’ - fragments of past human experience preserved through the aeons in individual human brains as if encoded at the genetic level. While investigating the mystery of Hobbs Lane, the site of the crash, Quatermass hears the call of humanity’s ancient alien ancestry echoing time and again through the centuries.

Penetrating the Earth: the rather phallic Martian pod

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

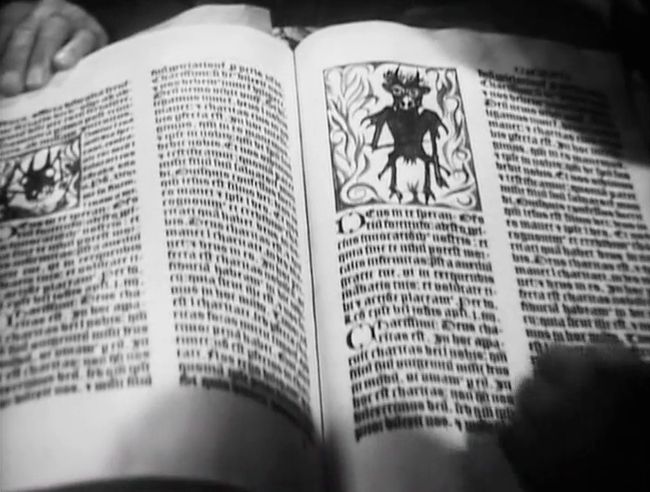

It’s a theme Kneale would return to in Quatermass, in the nursery rhymes and local legends and superstitions that surround the stone circles raised by Bronze Age Britons to mark the sites of past extraterrestrial visitations. Back in 1958, though, it was Medieval manuscripts, gargoyles and street names that tell of humanity’s ancient past, not to mention a long history of ghosties and ghoulies and things that go "bump" in the night all seen and heard in the vicinity of the buried space pod.

In Quatermass and the Pit, these echoes are literally diabolic, allowing the writer to invoke supernatural horrors to put the willies up his audience. Notions of the Devil stalking the Earth aren’t as unsettling now as they would have been in the more religious 1950s, but the physical and mental effect of the Martian ship’s psychic echoes on the drill operator Sladden - not to mention the clever, trick and treat special effects used to convey the psychokinetic storm breaking around him - still thrill.

The Martian, of course, is the Devil, the Christian fiend subsequently formed from memories buried as deeply in the human psyche as the space capsule was in the London clay. It’s an idea one 1970s Doctor Who production team was to adopt and use in a more literal sense: the alien Daemon Azal conjured up in a Devil’s End long barrow by the Master is not some vaguely diabolic prototype but the real thing, albeit amoral rather than evil.

Humanity’s ancient enemy revealed through history

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

Like Jon Pertwee’s Doctor, Quatermass is the arch-sceptic. No belief in magic or the supernatural for him - these are simply phenomena not yet accessible to current technology and understanding. Ironically, the professor’s rival, Colonel Breen, called in by Quatermass to speed the efforts of the Army bomb disposal team sent in to defuse the buried rocket, doesn’t believe in any of it either. But his mind is closed to the implications of the scientifically recovered evidence. For him, the remains, the craft and the mummified Martians are tricks fabricated by desperate Nazis out to scare brave Blighty into submission.

That said, even Quatermass himself initially distances himself from talk of the occult. The true experimentalist, it’s only by experiencing at first hand the weird phenomena present in Hobbs Lane that he comes to realise a scientific truth might lie behind what earlier ages considered the work of goblins, imps and demons. As Arthur Clarke said, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Writing a scientific take on the supernatural would serve Kneale well: he went back to it in his 1972 screenplay The Stone Tape.

And magic-seeming technology comes to Quatermass’ rescue: a mind-reading device devised by Roney to visualise the mental realms traversed by trance-bound Shamans. Quatermass’ brain is too ordered, too modern to pull a picture out of our racial memory bank, but Roney’s fey assistant, Barbara Judd, is able to call up images of Martian hive wars - the prototype of humanity’s own violent and anti-racial urges.

Devilgate Drive

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

And yet, when the space pod unleashes a storm of psychic energy on the people of London after being activated by the electrical energy fed into the pit for a live TV broadcast of its final exposure as a fake, it’s good old-fashioned iron - legendarily the enemy of the supernatural, and here in the form of an old chain used to drain energy away from the pod to Earth - that saves the day.

And, like America during World War II, Roney, the man from across the Atlantic, arrives in the nick of time to help Quatermass, now too weak to resist the onslaught of evil. It’s Roney, not Quatermass, who shorts the pod’s power supply, sacrificing himself in the process, but saving London and civilisation.

If science and technology helped Quatermass defeat the "devil" in the pit, it also ensured the survival of the serial itself.

Bringers of war

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

Quatermass and the Pit’s six 35-minute episodes were captured on electronic cameras during their near-live performances at London’s Riverside Studios in Hammersmith during November and December 1958. Pre-shot sequences were fed in from telecine’d 35mm film during recording.

The stoney tape

Back then, the BBC had yet to use videotape archiving - tape was just too expensive - so Quatermass and the Pit was taped first and then recorded on 35mm film upon transmission. With the film safe in the can for posterity, the tape could be wiped and used for future productions.

To record each episode, the output from the videotape was presented on a large CRT monitor which was then filmed. The trick, discovered after Quatermass II had been recorded in 1955, was to tie the opening of the film camera’s shutter to the appearance not of the first but of the second of the two interlaced fields. With the shutter closed, the first field was ‘written’ to alternate lines of the CRT’s phosphor screen. At the same time, the next film frame ratcheted round into place ready to be exposed. Because the phosphor holds the image for a fraction of a second, there was just time to open the shutter, write the second video field onto the monitor’s empty lines and expose the film to a complete picture before the first field’s lines faded from view.

Cec Linder (as Matthew Roney) ponders the human past - and that he has six years to go before playing CIA agent Felix Leiter in Goldfinger

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

Make the first field overly bright so that the phosphor glowed for longer, and the second field pale enough to match the now fading first field lines, and you had a complete, full-resolution image of even intensity across the frame. The result was a high-quality recording that was not only used to repeat the programme a year later, but also ensured Quatermass and the Pit survived the BBC’s infamous purge of old videotape in the 1970s.

The picture was of sufficient quality to be released on VHS in the late 1980s, and it provided the informally instituted Doctor Who Restoration Team with good material to work from when they came to reconstruct and remaster all the BBC Quatermass serials for DVD in the early 2000s.

Not only the picture, but the serial itself stands up well to modern eyes. Yes, it’s in black and white, and shot in a 4:3 aspect ratio at a time when editing was expensive and so all but the most extreme gaffes had to be left in, but with strong writing and a very able cast, Quatermass and the Pit grabs your attention and holds it.

From the melting pot of London to the melting pod

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

Director Rudolph Cartier had a bigger budget for Quatermass and the Pit than he had for Quatermass II, but the difference it made, if any, is well hidden by the respective picture qualities of the recordings left in the BBC archive. For me, what makes the third Quatermass serial stand above its predecessor is André Morrell’s performance as the professor. Even when forced to don the ridiculous and unwieldy prop that is Roney’s mind visualising machine, he’s always convincing. He was as able to bring out the character’s bolshiness, arrogance, pique and cheekiness just as well as his scientific authority and intelligence. For me, he had Bernard Quatermass nailed - better even than Sir John Mills.

But it’s a good, intelligent cast throughout. Cec Linder is spot on as the stressed yet ebullient anthropologist Matthew Roney; Anthony Bushell strikes exactly the right tone for the solidly soldierly, unimaginative but never dim Colonel Breen - he’s no Blimp; and John Stratton is appropriately down-to-Earth bomb disposal man Captain Potter. Kneale’s writing gave the actors so much to work with.

In particular, perhaps, journalist James Fullalove, played by Brian Worth. An old newspaperman himself, Kneale has some fun with Fullalove but ultimately gives him a heroic yet fatal role, just as he does with the journalist Conrad - played by a long pre-Master and beardless Roger Delgado - in Quatermass II.

André Morrell: the best Bernard?

Source: BBC/2 Entertain

Following the broadcast of the final episode of Quatermass and the Pit in January 1959, it would be almost 20 years before Professor Quatermass returned to British TV screens with a new challenge. Yet again, he would be played by a new actor, but he would also return in colour, on a different channel and thrill an entirely new, younger audience. ®

Next Lovely lightning: The Quatermass Conclusion