Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/07/22/quatermass_ii_the_quatermass_ii_anniversary/

Goodbye Blighty: The alternative reality of Quatermass II

Swapping Pimms for Schnapps and Vodka

Posted in Personal Tech, 22nd July 2013 09:57 GMT

Quatermass at 60 The Quatermass Experiment saw Nigel Kneale lay the foundations of what, in the era of trilogies, prequels, sequels and reboots, the entertainment biz would almost certainly call "a franchise". Kneale created Professor Bernard Quatermass, a gifted British rocket scientist whose adventures would be told and re-told eight times through TV and cinema between 1953 and 2005.

Kneale created gripping TV from the start. He emptied the pubs and streets of Great Britain with the story of a failed rocket mission, lost astronauts and alien possession in The Quatermass Experiment on the BBC.

Pundits theorize about how Kneale succeeded in dragging people out of the pub and establishing a figure that would be told and re-told over 50 years. This wasn't the Coronation or even England winning the World Cup in 1966 - understandable fodder for the masses.

The dominant theory is that Kneale tapped into Britons' fears and paranoia of changing times: a crumbling empire, mass immigration, the rise of the Iron Curtain, A-bomb experiments and a dawning realisation of nuclear war.

But Kneale did more than that.

Put yourself in the shoes of a Brit in the 1950s. Space, for you, has consisted of the swashbuckling adventures of Dan Dare, Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers in comics and Saturday-morning cinema of the 1930s and 1940s, where extraterrestrials are familiar humanoid types and can be easily dispatched with a smoking laser gun.

Shifting, shapeless, invasive, mind controlling? Kneale's ETs were creepy adversaries bent on dominating us and getting under our skins - literally.

Yet, in The Quatermass Experiment Kneale had already shown us the alien. Like James Cameron in 1986's Aliens, where do you go once Ridley Scott's done the chest explosions and revealed what the beast looks like? Answer: you approach the story from a different angle.

In the 1955 broadcast of Quatermass II, you barely see the alien - it's buried deep at the end of episode three and then it's only glimpsed briefly. Instead, what Kneale achieved in Quatermass II was to capitalize on Britain, its culture, society and people and to turn the familiar into a horrible alien thing.

The brilliance of Quatermass II is Britain is the canvas for a chilling "what if". And, in this way, Kneale fits into strong but rarely revealed tradition of British storytelling running from the era of HG Wells to the film-makers of Ealing Studios and the 1960s. It's this which spelt success for Quatermass II and set the stamp on the Quatermass "franchise."

The Quatermass II plot is simple. It even revisits a theme of The Quatermass Experiment, of an alien force using humans as its hosts and controlling them.

The picknickers: you are not in England now, my little man

The extra-terrestrial pests this time are crash landing on Earth in artificial meteorites. The humans they assimilate either run a massive industrial plant producing a toxic soup that’ll be used to kill life on earth and sustain the aliens, or they're being returned to government and society to be suitably docile and malleable.

Quatermass himself does some super sleuthing to uncover the alien conspiracy and then leads the workers building the aliens' industrial plant in a bloody riot and takeover. Meanwhile, his rocket team discovers the aliens are coming from an asteroid hidden from detection using some clever space navigation. The climax is Quatermass landing and exploding a nuclear rocket from his British Experimental Rocket Group on the asteroid, killing the aliens and breaking the telepathic link between them and their humans hosts.

Judged by today’s standards, the telling is shaky: lines, like the score, are dramatic, and words frequently get trampled by actors missing their cues and speaking too soon. There’s soliloquy, dramatic pauses and stares off camera. And when people die, there’s stumbling, twisting and choking. This is radio on TV. And don't expect a Doctor Who-style one-hour romp - Quatermass II is six finely-crafted half-hour episodes broadcast once a week, so you're watching a single plot spun over one-and-a-half months.

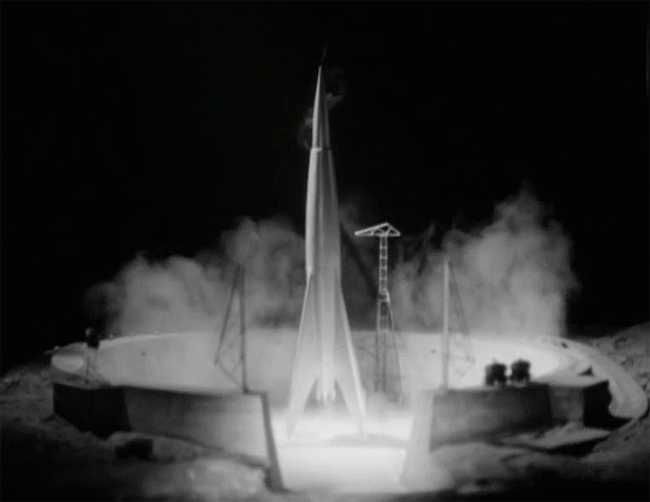

The effects are wobbly but ambitious: models of the industrial plant swirling with oversized smoke are interspersed with real-life action while the nuclear rocket ascends with the grace of a Thunderbird on a piece of wire.

One tasty titbit is a model of the English countryside receding as the rocket blasts off towards the alien asteroid, like the viewer is looking back from the rocket. It’s like Slim Pickens in Dr Strangelove, only run in reverse.

More sci than fi

The dialogue might be o-v-e-r dramatic, but it’s also factual. This isn’t the sci-fi of David Tennant's loopy Dr Who, where scientific solutions comes from waving a sonic screwdriver around. Here, you get an education - so sit up at the back and pay attention! Quatermass and his team deduce the aliens are “probably” coming from one of the moons of Saturn “800 million miles away”.

The asteroid launching the meteorites is 30,000 miles away. “That sounds like a lot, but in astronomical terms it’s next door,” we are informed. We learn that the asteroid launching the meteors is at “perigee” - the closest point in its orbit to Earth. Your knowledge of, and ability to use, these key facts will be tested in the playground tomorrow morning.

The core characters are tightly drawn. Quatermass’ faithful assistant, Welsh maths wizard Dr Leo Pugh; public-school army officer Captain John Dillon, the boyfriend of Quatermass’ daughter Pauline. As for Pauline, she is a Mrs Miniver in the making, prone to bouts of “silliness” but with a square jaw in the face of the enemy.

Bernard Quatermass is an energetic, silver haired, three-piece-tweed-suit-wearing man of science played by John Robinson. He is not the worn down, raincoat-wearing prof of two years ago, played by Reginald Tate. Our new Quatermass doesn't suffer fools gladly; he cuts down foppish newspaper columnists, complacent union men and boozy workers with the timeless: “Permit me to explain, I’m a scientist.”

One of many striking images for a 1950s audience barely used to the BBC

However, it’s Kneale's peripheral characters and stories that do more to shock as the drama of the “what if” is played out on the canvas of Britain and society. We have rioting workers. Initially drunk and dismissive of Quatermass in the pub when he tells them the purpose of the plant they’ve built, they soon turn.

It all starts in a suitably British fashion, with the labourers marching up to the plant chanting: “We demand to see the management, we demand to see them now!” But quickly they turn into an armed insurrection shot down by the plant's security guards, led by a flat-capped union firebrand called Paddy who wields an anti-tank grenade launcher.

Impossible, you say? Couldn’t happen here? This is 1955, just two years after German workers rioted and were gunned down by Soviet troops in East Berlin. The rise of the worker is a reality in Britain at this time. Quatermass II was broadcast in October 1955 following a state of emergency that was declared in June as two of Britain’s railway unions went on strike - not over money but over preserving separate pay scales. Trade union power was on the rise.

The guards at the aliens' industrial plant are mean faced and monosyllabic. They wear bulky uniforms and rounded helmets, making them look like German paratroopers from the Second World War. Their firearms sport a drum magazine and look a lot like a Thompson sub-machine gun. In a shot of the workers' riot worthy of Sergei Eisenstein (of Battleship Potemkin fame), one guard advances through curling smoke squarely towards the viewer sitting in their seat, firing his gun at them, coming out the screen.

Worse, these guards are humans – assimilated into the hive mind after being exposed to the meteorites. So these are humans shooting down other humans.

Don't get too friendly, chaps: Prof. Bernard Quatermass (left) with dependable yet doomed boffin pal Dr Leo Pugh

It’s all a timely mediation on collaboration for a nation with the taste of World War II fresh in its mouth – and whose Channel Islands brothers fell under the Nazi jackboot.

This would have looked familiar, too: pubs and offices around the plant sporting posters warning against talking to strangers and to keep their work secret. Government propaganda posters during the war warned that loose lips sink ships – anyone watching in 1955 would have remembered that. The alien invaders have subverted this patriotic responsibility and quietly turned it against us.

In Quatermass II, it's not just humans who are assimilated; Britain is being transformed, too. The green and pleasant land of shop keepers and cricket greens is being bulldozed. The aliens’ plant – in real life a Shell refinery in Essex, according to the Quatermass II credits – is a monument to steel and steam. The story says the plant was built on the site of a village bulldozed in just one night by the invaders.

The plant’s builders – those rioting workers – have been housed in a new village near the plant, with straight streets and identical box-form houses. A Soviet factory town or a British new town? Concrete developments like Crawley in West Sussex were up and running by the time of Quatermass II thanks to a 1947 law introduced by the Labour government, committed to equality for all and a cradle-to-grave welfare state.

And the takeover is gradual. This is not a war, with clear battlefronts. It's an infiltration, with politicians and journalists assimilated, and where the police are either unwilling or ill-equipped to investigate stories of alien invasion. The takeover is global, too, as Quatermass realises. Sure, destroy the plant in Britain, but there are factories all over the world producing the aliens’ toxic filth.

If the “what if” is compelling, so was the imagery and violence for the time

A family of three are happily picnicking on the beach near the plant when the guards pull up in their truck to shoo them away. Mum in her best hat and coat doesn’t want any trouble and is ready to go but dad ain't gonna get pushed around and he stands up to the guard, who unslings his weapon. Cut to Quatermass poking around the plant and we hear distant machine-gun fire. Later, we see the family’s car being towed into the plant with an arm swinging lifelessly from the car’s open window.

The aliens are cruel. They trick three union men in Paddy's armed band into surrendering with promises of safety. Later, the guards stuff their bodies into the pipes of the industrial plant to block the flow of oxygen being pumped in by Paddy’s men from the control room to kill the aliens.

Death is indiscriminate. Dr Leo Pugh is assimilated by the aliens but we don't know it until he's accompanying Quatermass on the nuclear rocket to the aliens' asteroid. Under their mind control he pulls a machine gun on Quatermass and fires but is blasted into space by the gun's recoil. He's alive but as good as dead - Quatermass is alone on the ship and this is 1955, so there's no such thing as space walks or deep space rescue.

As Quatermass primes the core of the rocket’s nuclear engine to explode we hear Pugh’s pitiful disembodied screams over the ship’s radio for Quatermass to stop. When the rocket destroys the aliens the telepathic link between human host and alien is broken. Unfortunately, that means Dr Pugh is once again himself, only he’s now floating beyond help in the cold reaches of space and doomed to run out of oxygen. In the days of Flash Gordon, central characters were regulars but this is like Aliens, where we get to love - then lose - each colonial marine to the creatures.

The final horror is that in Quatermass II science does not necessarily have the answer to your problem. The 1950s is an decade of supposedly limitless human achievement, with A-bomb tests and consumer gadgets that would change our lives forever.

Quatermass II initially reflects this, with Quatermass building a nuclear-powered rocket on behalf of the government to serve as a shuttle for the colonisation of the moon. Except the rocket doesn’t work – it malfunctions on a test flight in Australia, resulting in a huge nuclear blast that kills the lunar plans. The aliens, meanwhile, have come from far further afield than the Moon and they're using sophisticated stealth flight techniques that most people can’t understand, according to Dr Pugh before he's offed. The humans' only way of defeating this superior enemy is a desperate kamikaze mission – using one of Quatermass’ faulty nuclear spaceships as a flying bomb.

Human achievement is not only frail, it seems, but it’s also limited in its vision and its capabilities.

Smoke and string: Quatermass' British Experimental Rocket Group's nuclear-powered craft is one of the series' special FX models

Over the decades sci-fi has become a creative backdrop for the allegorical storyteller and spinner of metaphor – just like the Western. In this respect, Kneale told a story that filtered some of what he'd have read or experienced – WWII occupation, workers rioting in East Berlin against the Soviet authorities, growing union power, industrialization and modernization.

From the science perspective of science fiction, Quatermass II is the dark child of others' adventures, with complicated alien adversaries, cruel deaths and questionable boffinry. But Kneale did more than “rip from the headlines” or just complicating the black-and-white stories of kids who grew up before and during WWII.

He capitalized on a strand of British storytelling called invasion literature. It's a strand that would have played well to an audience of all ages and walks of life immediately following WWII, people who saw their lives - and way of life - threatened. In that tradition we have literature such as The Battle of Dorking - Reminiscences of a Volunteer and HG Wells’ War of the Worlds, both of which shocked Victorians with stories of continental or extraterrestrial invaders destroying the green and leafy market towns of Surrey.

Later we had Ealing Studios’ Went the Day Well, and Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo's It Happened Here, which tell of German landing and occupation, with villagers committing acts of murder in the name of freedom and Britain either donning the swastika or resisting while the Bosche goosestep through Whitehall.

The story of an alternative reality is compelling, even gripping if it involves the defiling of everything you hold familiar or sacred. It's certainly more enduring than the reality TV of a new Queen or sports trophy, and it served Kneale well with Quatermass II and "the franchise." ®